This too, I know, that England does not love coalitions.

We are trying to form a Government that should rally all the nation and set forth the energies of the people. I have not the slightest doubt about our victory, but I have no doubt at all as to the price that will have to be paid or the effort that will be needed.

The Cabinet in the garden of 10 Downing Street on 24 October 1941, together with military chiefs and other officials.

Front Row (from left): Ernest Bevin, Lord Beaverbrook, Anthony Eden, Clement Attlee, Winston Churchill, Sir John Anderson, Arthur Greenwood and Sir Kingsley Wood.

Back Row (from left): Sir Edward Bridges (secretary to the War Cabinet), Sir Charles Portal (Chief of Air Staff), Sir Archibald Sinclair, Sir Dudley Pound (Admiral of the Fleet), A.V. Alexander, Lord Cranborne, Herbert Morrison, Lord Moyne, David Margesson, Brendan Bracken, General Sir John Dill (Chief of the Imperial General Staff), General Sir Hastings Ismay (Military Secretary) and Sir Alexander Cadogan (Permanent Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs).

AP/PRESS ASSOCIATION IMAGES

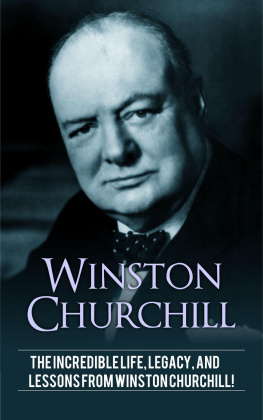

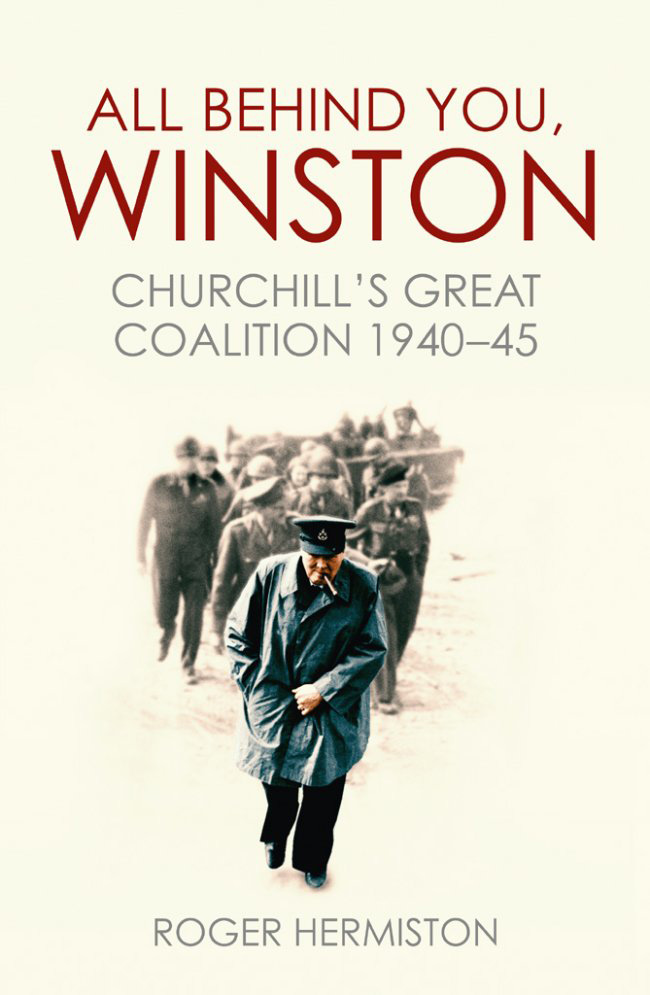

Churchills long and varied political life made him uniquely qualified to lead a wartime coalition. His air of defiance and optimism rallied the nation in a way no other could.

POPPERFOTO/GETTY IMAGES

Churchill visits a bomb-damaged home at the height of the Blitz in late 1940. He could provide stirring words on these occasions, but was also easily moved to tears by what he witnessed.

POPPERFOTO/GETTY IMAGES

Sir Archibald Sinclair, Liberal leader and Secretary of State for Air. He had fierce tussles in cabinet with Lord Beaverbrook during the Battle of Britain.

PICTORIAL PRESS LTD/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

The irrepressible and unconventional Brendan Bracken, Churchills close confidant and a successful Minister of Information.

MARIE HANSEN/THE LIFE PICTURE COLLECTION/GETTY IMAGES

Lord Beaverbrook was at the forefront of propaganda to mobilise the Home Front in the dark days of 1940. This was one of hundreds of posters produced by the Ministry of Information.

THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES/SSPL/GETTY IMAGES

Churchill leaves Downing Street with Sir John Anderson after a War Cabinet meeting in May 1940. Anderson was an indispensable figure: towards the end of the war Churchill advised the King that if he and Eden were killed, Anderson (then Chancellor) should become Prime Minister.

FOX PHOTOS/HULTON ARCHIVE/GETTY IMAGES

The redoubtable Ernest Bevin at his office in the Ministry of Labour. Emergency legislation gave him absolute control over the working lives of every Briton.

HULTON ARCHIVE/GETTY IMAGES

Lord Halifax, then Foreign Secretary, and Anthony Eden, War Secretary, leave Downing Street after a tumultuous War Cabinet meeting on 28 May 1940. Halifax had just presented the case for suing for peace with Germany.

FOX PHOTOS/GETTY IMAGES

Herbert Morrison, master of the photo opportunity and the pithy phrase, ferrying a sack of coal outside the Ministry of Supply headquarters in July 1940.

POPPERFOTO/GETTY IMAGES

The only two women in Churchills war ministry. Florence Horsbrugh (seated) and Ellen Wilkinson confer in April 1945 during the conference in San Francisco that established the United Nations.

AUTHORS COLLECTION

Sir Stafford Cripps. In early 1942 he was the most popular politician (bar Churchill) in the country, and even briefly viewed as his possible successor.

THOMAS D. MCAVOY/THE LIFE PICTURE COLLECTION/GETTY IMAGES

As the war developed, Clement Attlee and Anthony Eden formed a powerful axis in the area of foreign affairs - where they saw it as their task to resist some of Churchills wilder impulses.

DAVID E. SCHERMAN/THE LIFE PICTURE COLLECTION/GETTY IMAGES

A preoccupied Lord Beaverbrook prepares to address a conference on the conscription of labour in January 1941: his great rival, Ernest Bevin, in more jocular mood, stands behind him. Other Government ministers present are Oliver Lyttelton (left) and Sir Andrew Duncan, with Bevins junior minister Ralph Assheton alongside him.

KEYSTONE/GETTY IMAGES

Consulting amicably enough early in 1945, but Bevin and Morrison nursed a deep-seated mutual dislike. However, their personal differences did not prevent them joining forces to harry Churchill over reconstruction.

IAN SMITH/THE LIFE PICTURE COLLECTION/GETTY IMAGES

A night off at the Opera House on 1 May 1945 for four of Britains delegation to the United Nations meeting in San Francisco Clement Attlee, George Tomlinson (junior minister in Labour department), Ellen Wilkinson and Florence Horsbrugh.

PETER STACKPOLE/THE LIFE PICTURE COLLECTION/GETTY IMAGES

Clement Attlee takes tea with his constituents in Limehouse. He grew in stature as the war progressed, valued especially for his efficient committee work and expert chairing of War Cabinets when Churchill was absent.

POPPERFOTO/GETTY IMAGES

F or this book I interviewed a number of individuals who had fascinating civilian and military roles in World War Two: amongst them, a teenage Bevin Boy, a very young secretary in the Cabinet War Rooms, and an underage Home Guard recruit who later went on to become a navigator in a Wellington bomber. Given the passage of time, it was always improbable that I would get to meet a significant, living, former member of Churchills war ministry politician or civil servant. But I did interview many people in the course of my research who knew a good deal about the books main characters, either through family connection or other association. In particular I wish to thank Lord Woolton, Charles Sandemann-Allen, Earl Attlee, Lady Attlee, Lord Beaverbrook, Baroness Linklater, John Thurso MP, John Julius Norwich and Mrs Jane Kerr for their time and their various vital insights into their famous ancestors, and for giving me access to important documentary material. Lord Carrington served in Churchills 19515 administration, and he gave me splendid character sketches of some of the wartime ministers he personally knew who had survived to serve WSC again.

Caroline Balcon and her staff made me very welcome in the Prime Ministers Room in the House of Commons, where one particular crucial, memorable scene takes place although a number of other War Cabinet meetings were also held there between 1940 and 1945. Equally, I must thank Jane Ford and Nicky Luscombe for allowing me to spend a fascinating few hours looking round Cherkley Court, Lord Beaverbrooks dramatically situated old pile in Surrey.

I am also indebted to a good many others who provided stories, guidance and help of one kind or another Lord (Michael) Dobbs, Dr Paul Addison, Prof. Stuart Bell, Dr Anthony Seldon, Prof. Robert Self, Kenneth Baxter, Liz Todd, Eric Johnson, Joy Hunter, Derrick Clewley, Peter Fleming, Clive Robey, Nick Kerr, Diana Mackenzie, Martin Kinna, Ashley Cooper and Ben Perkins. Edmund Bradbury was an excellent, assiduous researcher on the subject of the Bevin Boys.