Table of Contents

ALSO BY LEN FISHER

Rock, Paper, Scissors

Weighing the Soul

How to Dunk a Doughnut

To Wendella, who has now survived four books, and has helped me to do likewise.

PATTERNS OF THE PERFECT SWARM: VISIONS OF COMPLEXITY IN NATURE

How Complex Patterns Emerge from Simple Rules in Physical and Living Systems

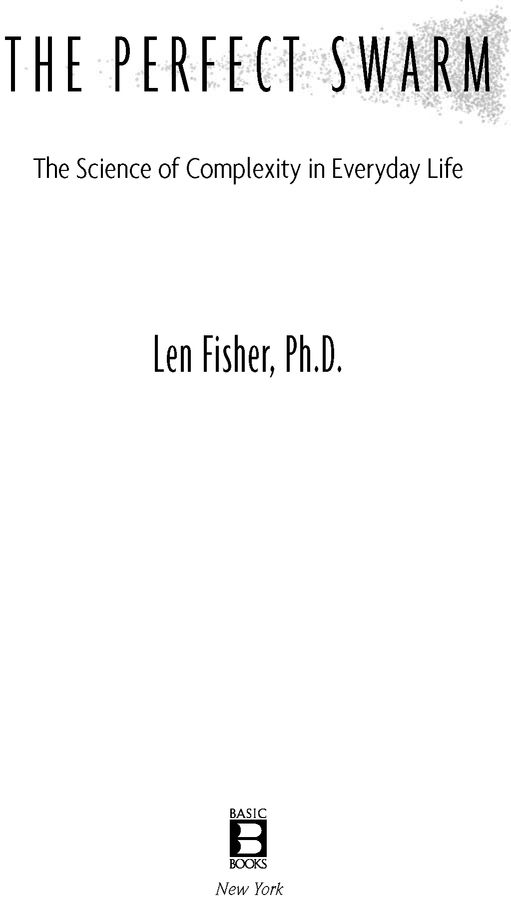

Pattern of Rayleigh-Bnard cells formed by convection in a layer of oil in a frying pan heated from below (see page 3).

COURTESY OF BEN SCHULTZ

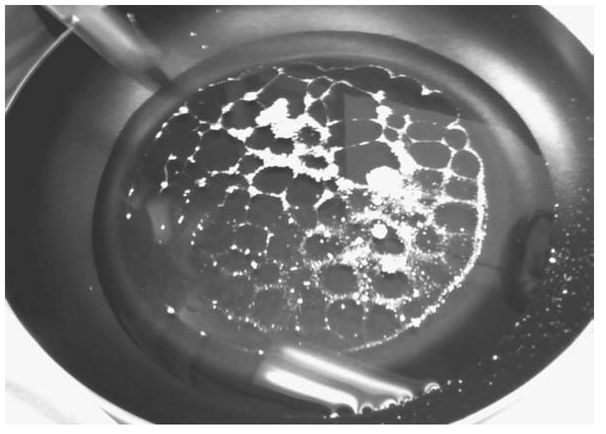

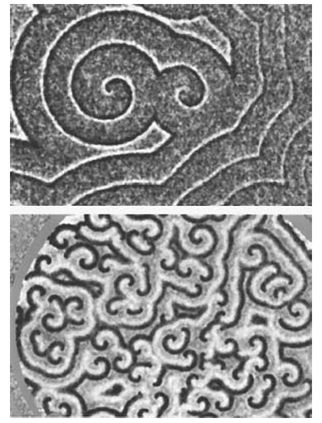

Patterns in coral at Madang, New Guinea, formed by walls of calcium carbonate secreted by individual polyps competing for space.

PHOTO BY JAN MESSERSMITH

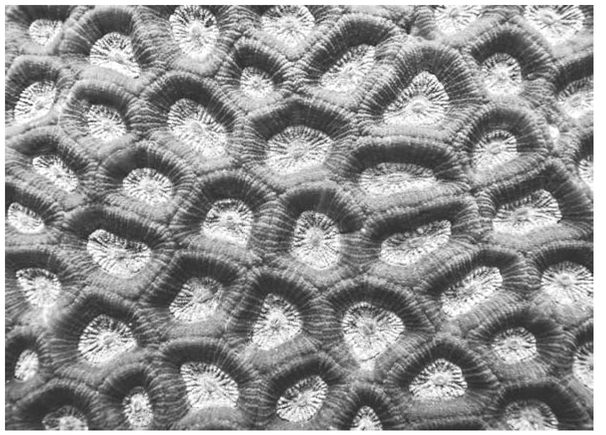

Pattern of reaction products formed in a petri dish by an oscillating chemical reaction known as the Belousov-Zhabotinsky reaction. The black dots are adventitious air bubbles.

COURTESY OF ANTONY HALL, WWW.ANTONYHALL.NET

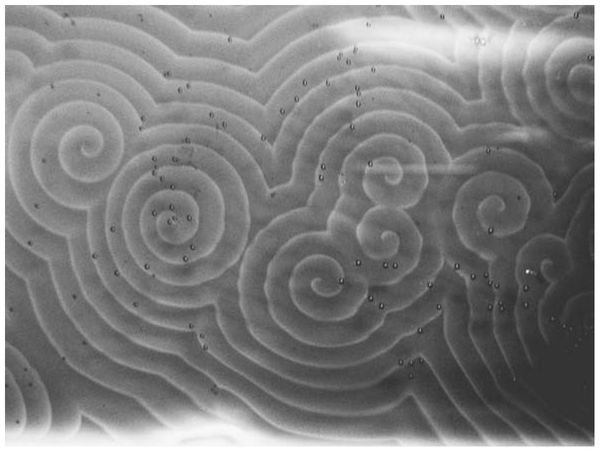

Patterns formed by tens of thousands of the soil-dwelling slime mold amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum, growing on the surface of a gel-filledpetri dish. Each individual is responding to chemical signals from its neighbors that warn of a lack of bacteria that are its main food. Ultimately the cells will aggregate to form a slug, technically called a grex, which can crawl through the soil much faster than the individual amoebae to find new bacterial pastures (see page 18).

COURTESY OF PROF. CORNELIS WEIJER, UNIVERSITY OF DUNDEE, UK

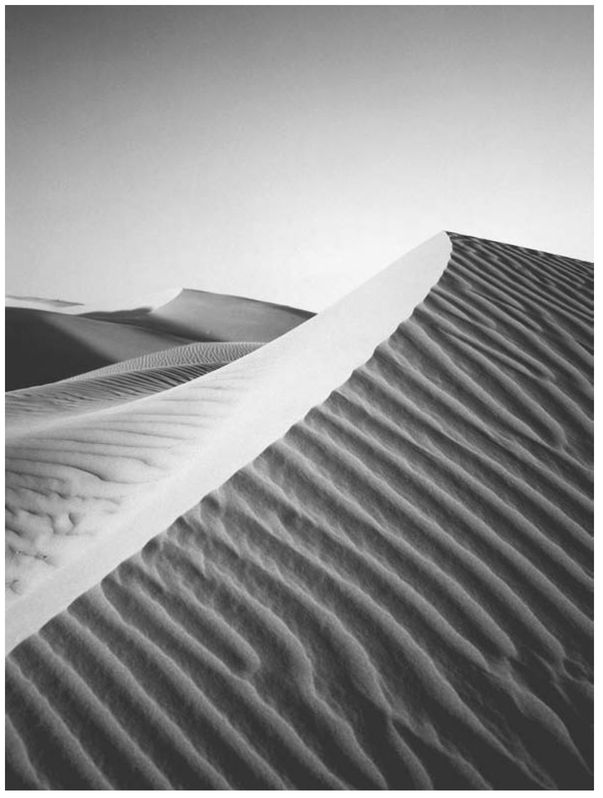

Stripes in the Algodones sand dunes of Southern California, formed by a combination of wind driving the sand up and the force of gravity pulling sand grains down (see page 2).

KONRAD WOTHEA/FLPA

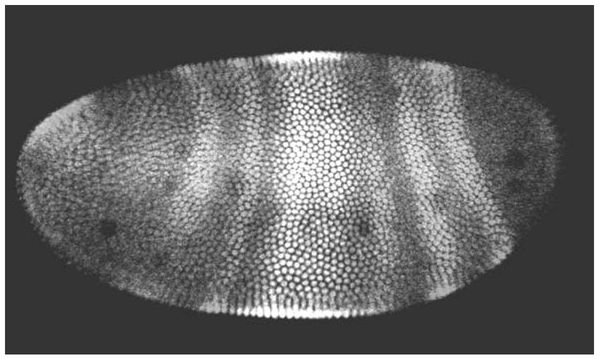

Stripes in the developing larva of a fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster). The stripes are formed by the selective differentiation of cells in response to the presence of distinct neighbors. Each stripe will ultimately develop into a different part of the adult bodywings, thorax, eyes, mouth, etc.

COURTESY OF JIM LANGELAND, STEVE PADDOCK, SEAN CARROLL. HHMI, UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN

Stripes on a tiger, once thought by some biologists to emerge from a balance of chemical gradients in a manner reminiscent of the Belousov-Zhabotinsky reaction. This tiger was photographed in Pench National Park, Madhya Pradesh, India in 2004.

ROGER HOOPER

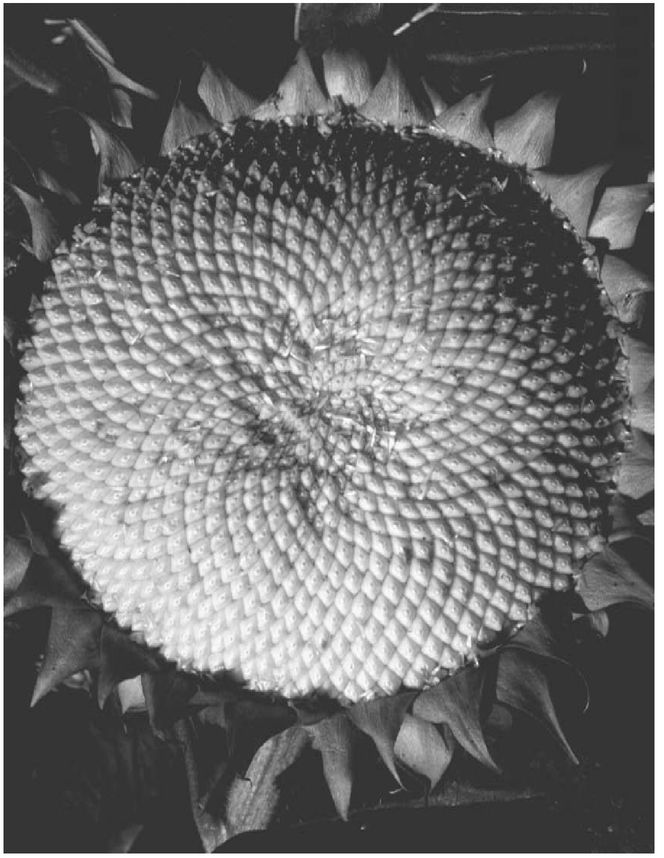

Spiral pattern in a sunflower head, an arrangement that allows for of the individual parts. This design is described mathematically by the Fibonacci sequence, in which each number is the two previous numbers (i.e. 0, 1, 1, 3, 4, 5, 8, 13, and so on).

COURTESY OF DR. HOWARD F. SCHWARTZ, COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY, WWW.BUGWOOD.ORG

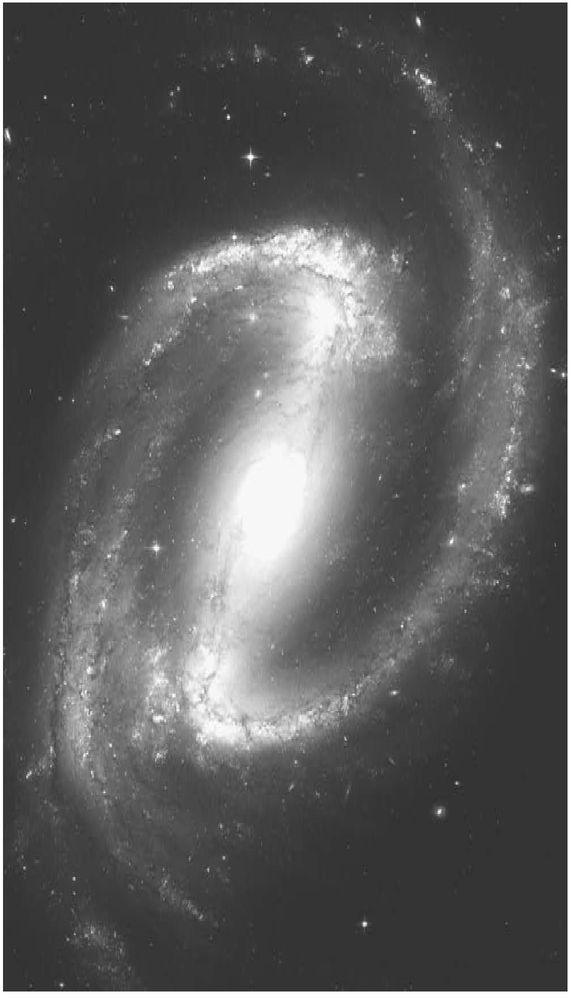

Spiral galaxy, whose formation is dominated by Newtons Law of Gravity and his three laws of motion. Barred Spiral Galaxy NGC 1300; image taken by Hubble telescope

COURTESY OF NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION (HTTP://HUBBLESITE.ORG/GALLERY/ALBUM/ENTIRE/PR2005001A/NPP/ALL/)

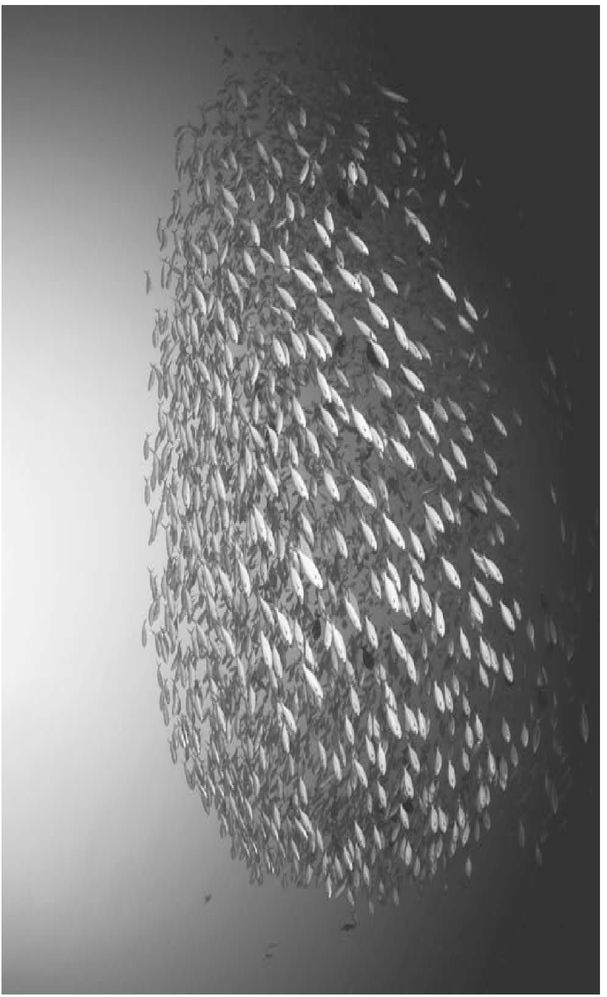

Self-organization in a school of fish, produced by each animal following Reynods three laws. Shoal of Robust Fusilier,Caesio cuning, German Channel, Micronesia, Palau (see page 12).

REINHARD DIRSCHERL/FLPA

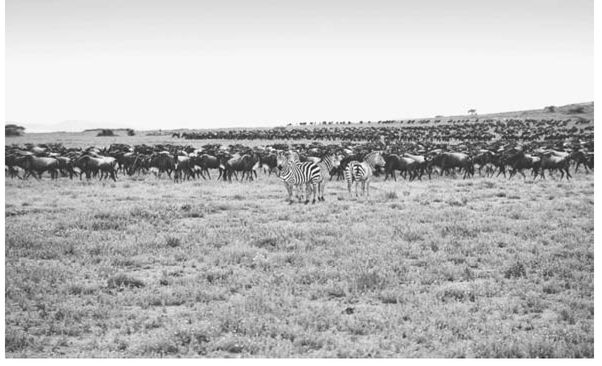

Self-organization in a herd of wildebeest crossing the Serengeti plain.

ALICE CAMP, WWW.ASTRONOMY-IMAGES.COM

Self-organization produced by social forces of people spontaneously forming lanes as they walk along a crowded street (see page 50).

COURTESY OF DIRK HELBING

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

It is a pleasure to acknowledge the many people who have acted as advisors, mentors, and muses in my efforts to produce a simple guide to complexity. Amanda Moon, my editor at Basic Books, has done her usual extremely thorough and helpful job, as has Ann Delgehausen, who has performed marvels with the copyediting. Particular thanks must also go to my wife, Wendella, who has painstakingly examined every chapter from the point of view of the nonscientific reader, suggesting a multitude of interesting examples and pointing out where new ideas needed a clearer explanation.

The book has also benefited greatly from the advice of world experts in the various fields that it covers. I have named them individually in the notes to the appropriate chapters and here record my collective thanks, along with my thanks to other friends and colleagues (scientific and otherwise) who have gone to a great deal of trouble to read the manuscript and offer suggestions that have contributed considerably to its gradual improvement over the course of writing. I cant blame any of them for errors that may still have crept in. Those, unfortunately for my ego, are my responsibility alone.

Here are the names of the people who helped, in alphabetical order, accompanied by the offer of a drink when we next meet: Hugh Bray, Matt Deacon, John Earp, David Fisher, Gerd Gigerenzer, Dirk Helbing, Jens Krause, Michael Mauboussin, Hugh Mellor, James Murray, Sue Nancholas, Mark Nigrini, Jeff Odell, Harry Rothman, Alistair Sharp, David Sumpter, Greg Sword, and Duncan Watts.

If I have omitted anyone, I can only apologize, and extend the offer to two drinks.