The Devil Is Here

in These Hills

The Devil Is Here

in These Hills

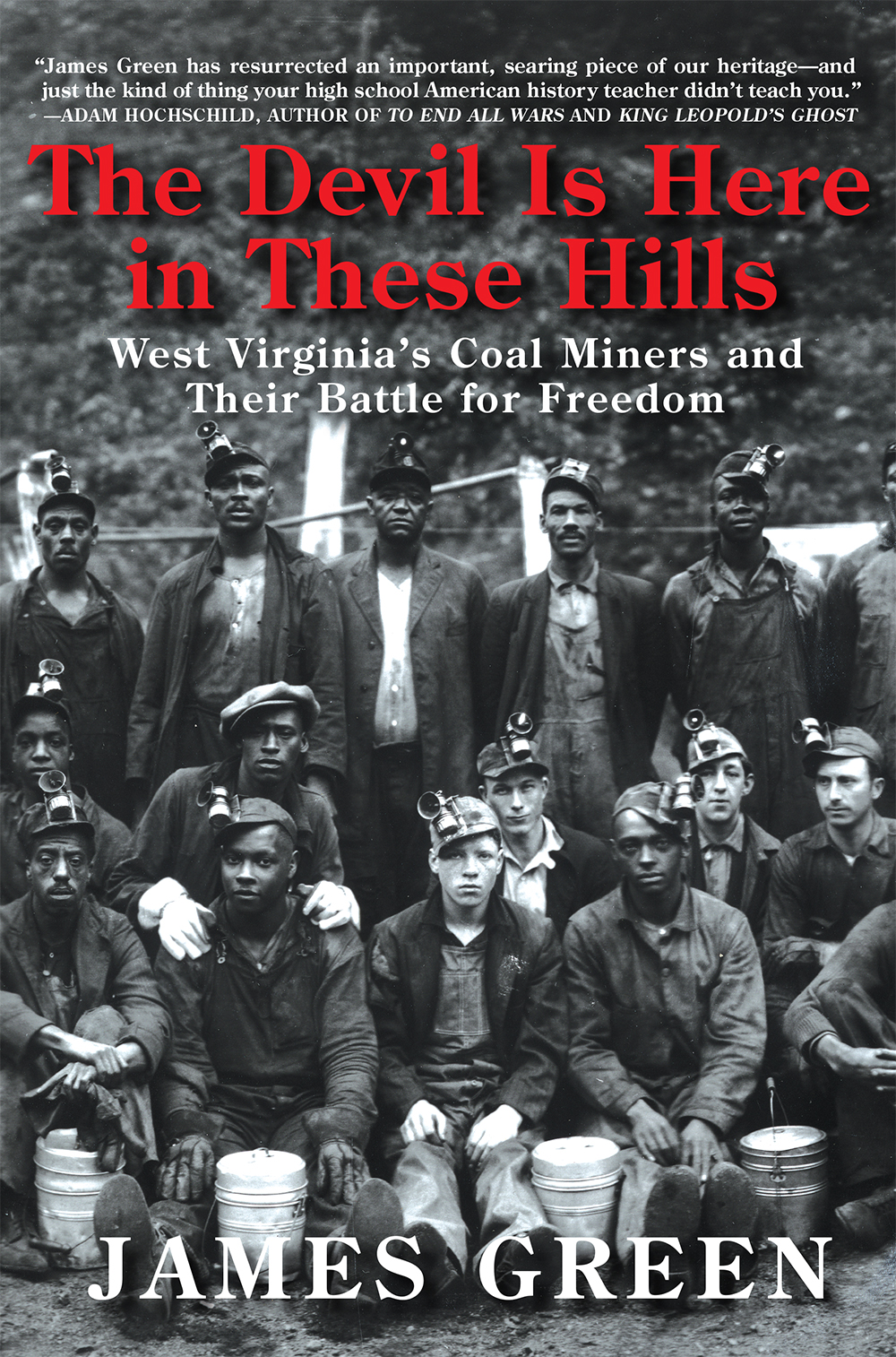

West Virginias Coal Miners

and Their Battle for Freedom

James Green

Atlantic Monthly Press

New York

Copyright 2015 by James Green

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part

or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to

Grove Atlantic, 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY 10011

or .

The author is deeply indebted to the West Virginia and Regional History Center at the West Virginia University Libraries, which granted permission to reprint thirty-seven photographs from their deep and rich collections. It would not have been possible to illustrate this book without the Center and its staff.

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN 978-0-8021-2331-2

eISBN 978-0-8021-9209-7

Atlantic Monthly Press

an imprint of Grove Atlantic

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

www.groveatlantic.com

In Memory of My Father

Gerald R. Green

19222012

Contents

Casus Belli, 18901911

: The Great West Virginia Coal Rush

: The Miners Angel

: Frank Keeneys Valley

: A Spirit of Bitter War

The First Mine War, 19121918

: The Lord Has Been on Our Side

: The Iron Hand

: Let the Scales of Justice Fall

: A New Era of Freedom

The Second Mine War, 19191921

: A New Recklessness

: To Serve the Masses without Fear

: Situation Absolutely Beyond Control

: There Can Be No Peace in West Virginia

: Gather Across the River

: Time to Lay Down the Bible and Pick Up the Rifle

The Peace, 19221933

: Americanizing West Virginia

: A People Made of Steel

: More Freedom than I Ever Had

The Devil Is Here

in These Hills

Prologue

O ne autumn morning in 1922, a middle-aged man with wavy hair and horn-rimmed glasses waited in Baltimores smoky Camden Station for a B&O limited that would take him to Huntington, West Virginia. He looked like an artist or college professor. In fact, James M. Cain had dreamed of being a professional singer like his mother, an operatic soprano, but writing came more easily to him. After editing an army newspaper during the war in France and teaching at a prep school, Cain took a job with the Baltimore Sun , covering police court and filing crime stories. But when he boarded the B&Os westbound limited that fall morning, Cain left the city on a different kind of assignment. He was headed over the Allegheny range, bound for the coal country of southern West Virginia. His mission: to search out the truth about what had caused a massive insurrection of armed coal miners the previous summer. In late August 1921, nearly ten thousand workers had marched over fifty miles of rugged terrain to liberate fellow union members who had been jailed under a martial law decree imposed on Mingo County, where a vicious mine war had raged for more than two years.

After the reporter passed through Huntington, he switched railroads and headed due south on the Norfolk & Western, along the Tug Fork River, and into the rugged valley where the Hatfields and McCoys feuded after the Civil War and whole families were exterminated, as Cain put it. This bloody history, and the folklore it produced, shaped outsiders impressions of the wild Tug River country, even after the region had become heavily industrialized and linked to the national economy. The legend of the feud led Cain, like other writers before him, to portray the Appalachian coal country as an American heart of darkness.

In the prose that would later make him famous as writer of hard-boiled murder mysteries and film noir screenplays, Cain described a setting fit for an epic drama.

As you leave the Ohio River at Kenova, and wind down the Norfolk and Western Railroad beside the Big Sandy and Tug rivers, you come into a section where there is being fought the bitterest and most unrelenting war in modern industrial history.

Rough mountains rise all about, beautiful in their bleak ugliness. They are hard and barren, save for a scrubby, whiskery growth of trees that only half conceal the hard rock beneath. Yet they have their moods. On gray days, they lie heavy and sullen, but on sunny mornings they are dizzy with color: flat canvases painted in gaudy hues; here and there tiny soft black pines showing against the cool, blue sky. At night, if the moon shines through a haze, they hang far above you... They are gashed everywhere by water courses, roaring rivers, and bubbling creeks. Along these you plod, a crawling midge, while ever the towering mountains shut you in.

Above the railbed, blue-black streaks of coal laced the hills for miles, jumping across rivers and creeks, now broken by some convulsion an eternity ago, now tilted at crazy angles, but for the most part flat, thick, regular, and rich. And along every ascending creek Cain saw curving ribbons of steel rails crawling up the mountainsides to mining operations wedged into the hollows. Here was a region where industry had been organized on a gigantic scale. To see it, he remarked, is to get the feeling of it: the great iron machinery of coal and oil, the never-ending railroads and strings of black steel cars, groaning and creaking toward destination. There was a crude outdoor poetry about it, but Cain knew that this marvelous achievement had been marred by a bloody industrial struggle that had lasted more than two years.

On his way up the Tug River Valley, Cain passed coal mines, some of them still closed down by die-hard union strikers, and he observed occasional clusters of tentssqualid, wretched places, where swarms of men, women, and children are quartered. And at nearly every train station, men in military uniforms scrutinized each passenger who alighted; they were state policemen, part of a strong force still on duty there, for the bloodshed in this valley had been so severe that Mingo County remained under martial law. The constables always walked in pairs and constantly looked over their shoulders. Everywhere, the reporter felt an atmosphere of tension, covert alertness, sinister suspicion, and he soon realized why.

In this untamed section of West Virginia two tremendous forces have staked out a battle ground. These are the United Mine Workers of America and the most powerful group of nonunion coal-operators in the country. It is a battle to the bitter end; neither side asks quarter, neither side gives it. It is a battle for enormous stakes, on which money is lavished; it is fought through the courts, through the press, with matching of sharp wits to secure public approval. But more than this, it is actually fought with deadly weapons on both sides; many lives have already been lost; many may yet be forfeited.

Some of the residents who were willing to speak with Cain told him grim tales of what they had witnessed.