WEYERHAEUSER ENVIRONMENTAL BOOKS

Paul S. Sutter, Editor

WEYERHAEUSER ENVIRONMENTAL BOOKS explore human relationships with natural environments in all their variety and complexity. They seek to cast new light on the ways that natural systems affect human communities, the ways that people affect the environments of which they are a part, and the ways that different cultural conceptions of nature profoundly shape our sense of the world around us. A complete list of the books in the series appears at the end of this book.

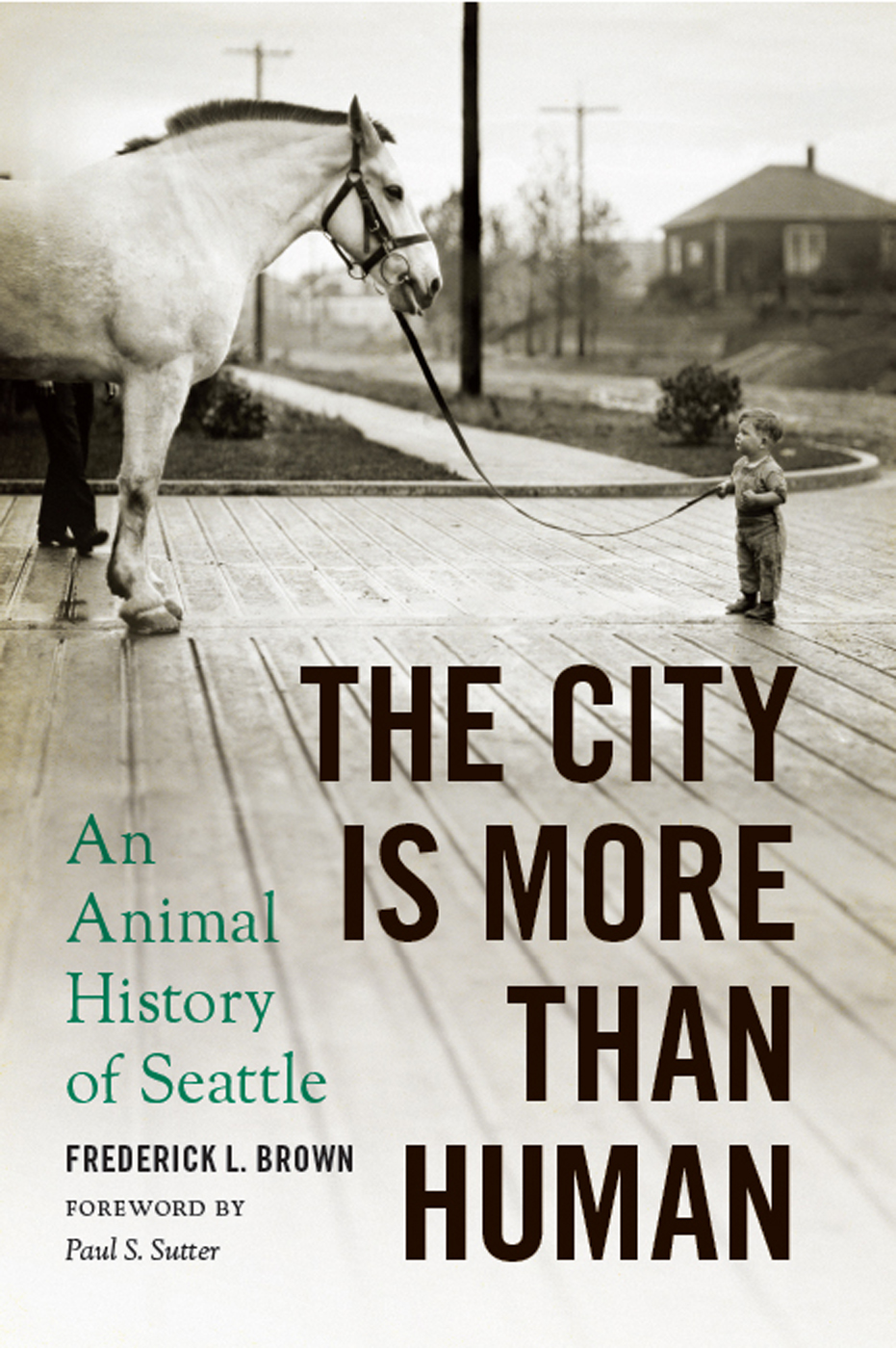

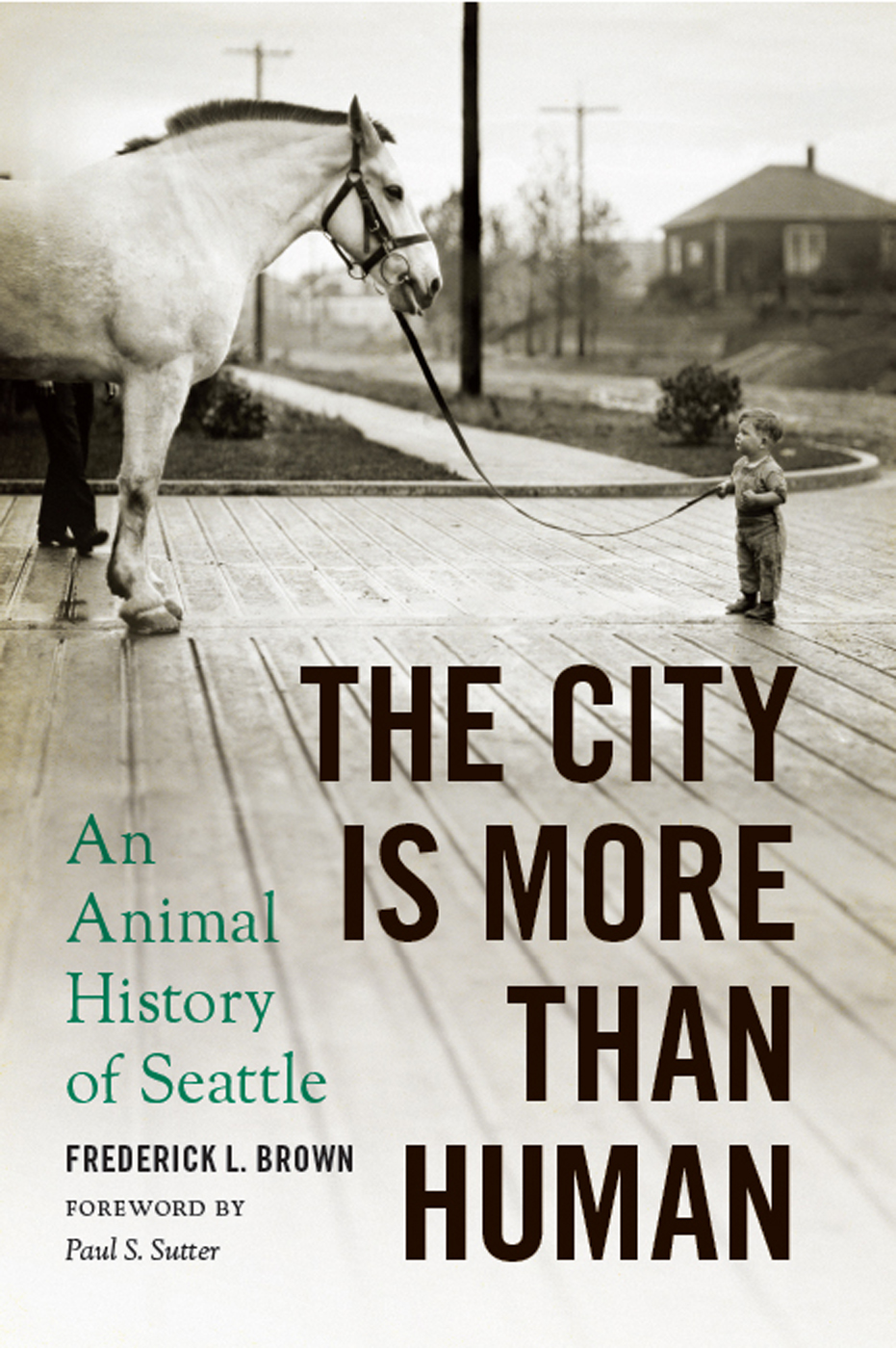

THE CITY IS MORE THAN HUMAN

An Animal History of Seattle

FREDERICK L. BROWN

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS

Seattle and London

The City Is More Than Human is published with the assistance of a grant from the Weyerhaeuser Environmental Books Endowment, established by the Weyerhaeuser Company Foundation, members of the Weyerhaeuser family, and Janet and Jack Creighton.

Copyright 2016 by the University of Washington

Press Printed and bound in the United States of America

Design by Thomas Eykemans

Composed in Sorts Mill Goudy, typeface designed by Barry Schwartz

201918171654321

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS

www.washington.edu/uwpress

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Brown, Frederick L., 1962 author.

Title: The city is more than human : an animal history of Seattle / Frederick L. Brown.

Description: Seattle : University of Washington Press, [2016] | Series: Weyerhaeuser environmental books | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016020377 | ISBN 9780295999340 (hardcover : acid-free paper)

Subjects: LCSH: AnimalsWashington (State)SeattleHistory. | AnimalsSocial aspectsWashington (State)SeattleHistory. | Human-animal relationshipsWashington (State)SeattleHistory. | City and town lifeWashington (State)SeattleHistory. | Social changeWashington (State)SeattleHistory. | Urban ecology (Biology)Washington (State)SeattleHistory. | Urban ecology (Sociology)Washington (State)SeattleHistory. | Seattle (Wash.)Environmental conditions. | Seattle (Wash.)Social conditions.

Classification: LCC QL212 .B76 2016 | DDC 591.9797/772dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016020377

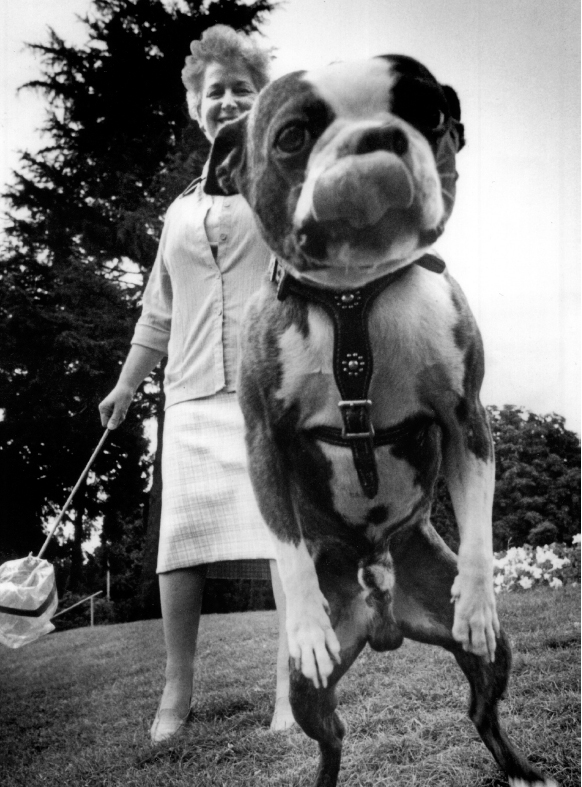

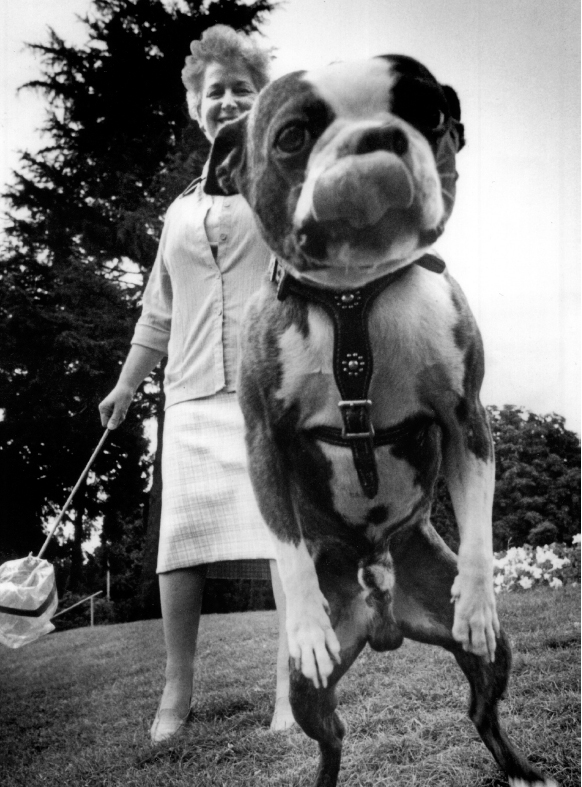

FRONTISPIECE: Peggy Mainprice and Tuffy in Volunteer Park, 1979. MOHAI, Seattle P-I Collection, 2000.107.50.17.001.

The paper used in this publication is acid-free and meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

To the memory of my mother and father

CONTENTS

, by Paul S. Sutter

BEAVERS, COUGARS, AND CATTLE

Constructing the Town and the Wilderness |

COWS

Closing the Grazing Commons |

HORSES

The Rise and Decline of Urban Equine Workers |

DOGS AND CATS

Loving Pets in Urban Homes |

CATTLE, PIGS, CHICKENS, AND SALMON

Eating Animals on Urban Plates |

FOREWORD

The Animal Turn in Urban History

PAUL S. SUTTER

One of the most revealing encounters an American has ever had with his animal nature occurred in 1700, when Cotton Mather, the influential Puritan minister, stepped outside to relieve himself against a wallto, as he put it, empty the cistern of nature. As he did so, a dog approached and joined him in his carnal act, putting Mather in a philosophical mood. What mean and vile things are the children of men, he mused. How much do our natural necessities abase us and place us on the same level with the very dogs! Not content to rest in this base animal world, Mather opted instead to use the force of thought, of faith-making even, to separate his human self: Yet I will be a more noble creature; and at the very time when my natural necessities debase me into the condition of the beast, my spirit shall (I say at the very same time!) rise and soar. Mather resolved to always use such occasions, when his animal nature called, to shape in his mind some holy, noble, divine thought. This commitment certainly reflected Mathers firm belief that as a human, and as a Christian, he existed on a qualitatively higher plane than did other animals, but his was also an anxious act of difference making in the face of contradictory empirical evidence and nagging self-doubt. With so exquisite a level of self-consciousness, as the great historian of environmental ideas Keith Thomas put it, Mather pledged to make himself believe, through thought and deed, something that he seemed not at all sure about. Mathers stark human-animal distinction was make believe in the most literal sense of that term.

Cotton Mathers fleeting encounter with a dog illustrates how much work has been involved in maintaining a strict boundary between human culture and animal nature, a border that has quietly delimited the territory of history. Now, there are certainly good reasons why animals have been peripheral to how historians have written about the past and narrated historical change over time. Animals do not speak or create archives from which we can gain access to their thoughts, and as a result, they have been voiceless and inscrutable actors easier to ignore than to engage across a vast communicative divide. There is thus a profound methodological challenge that confronts those who hope to integrate animal action and intention into their histories, one that we ought not to take lightly. But as importantlyand apropos of the Mather episodethere has also been a stubborn human exceptionalism at the core of the historical enterprise that has consistently made a difference between humans and animals. And, surprisingly, environmental historians have been relatively timid about challenging that exceptionalism. We have been more assertive in our arguments about how nature has mattered to the course of human history than we have been in suggesting that history itself might be more than human. As a result, we have largely left to other scholars the task of critiquing this willful and uneasy commitment to human difference, and of developing theoretically rich posthumanist or multispecies approaches to the study of our world and its history. Despite some notable exceptions, American environmental historians have been slow to take the animal turn in the humanities and social sciences.

Modern cities are the places where it has been easiest to make believe that we are separate from the animal world. As highly engineered habitats of human concentration, modern cities are forbidding environments for many animal species. Of course, there were and are important exceptions. Urban environmental historians have shown that animals such as pigs, horses, and other livestock were essential to the bygone organic city of the nineteenth century, which faded with technological modernization and elite-driven sanitary reform. Smaller and less visible animalsrats, pigeons, squirrels, cockroaches, bedbugshave also thrived in the human-built habitats of our modern cities, as the geographer Dawn Biehler has shown in her own wonderful contribution to the Weyerhaeuser Environmental Books series,

Next page