Copyright 2016 by Yanis Varoufakis

Published by Nation Books, A Member of the Perseus Books Group

116 East 16th Street, 8th Floor

New York, NY 10003

Nation Books is a co-publishing venture of the Nation Institute and the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address the Perseus Books Group, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107.

Books published by Nation Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Varoufakis, Yanis, author.

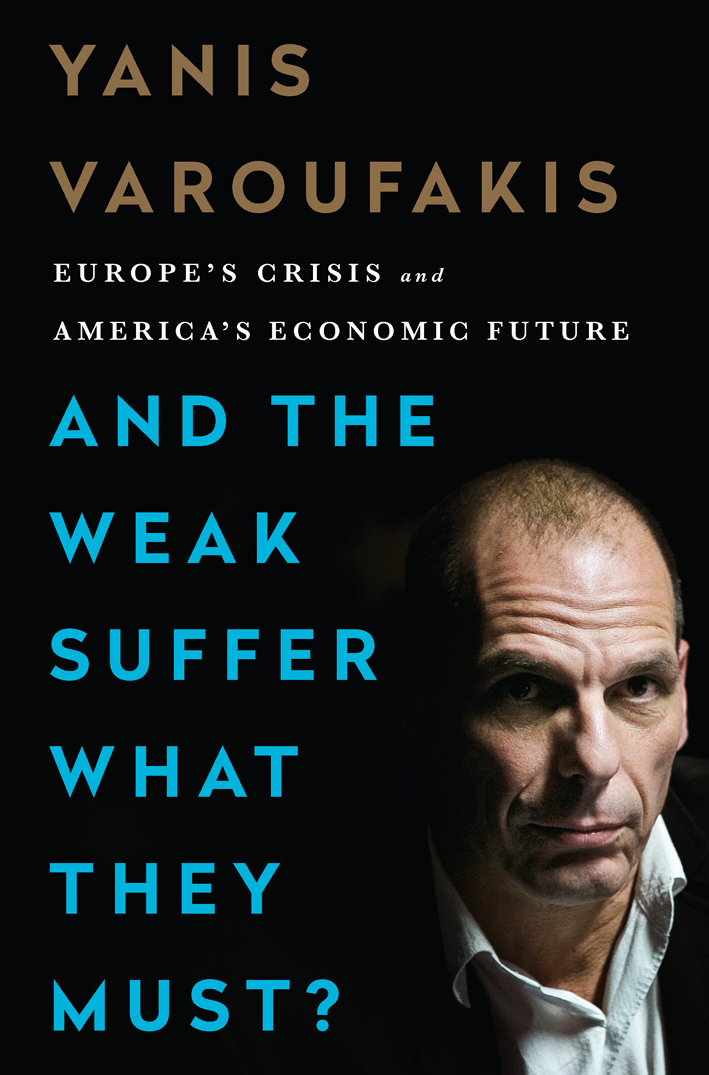

Title: And the weak suffer what they must? : Europes crisis and Americas economic future / Yanis Varoufakis.

Description: New York : Nation Books, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016001937 (print) | LCCN 2016003358 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Europe--Economic conditions--21st century. | Europe--Economic integration. | Financial crises--Europe. | Europe--Politics and government--21st century. | BISAC: BUSINESS & ECONOMICS / Government & Business. | HISTORY / Europe / General.

Classification: LCC HC240 .V37 2016 (print) | LCC HC240 (ebook) | DDC 330.94--dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016001937

isbn 978-1-56858-505-5 (eb)

Editorial production by Marrathon Production Services. www.marrathon.net

book design by jane raese

Set in 11-point Berthold Baskerville Book

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

FOR MY MOTHER ELENI,

who would have savaged with the greatest elegance and compassion anyone contemplating the notion that the weak suffer what they must

Table of Contents

Guide

CONTENTS

O ne of my enduring childhood memories is the crackling sound of a wireless hidden under a red blanket in the middle of our living room. Every night, at around nine I think, Mom and Dad would huddle together under it, their ears straining, bursting with anticipation.

Upon hearing the muffled jingle, followed by a German announcers voice, my six-year-old boys imagination would travel from our home in Athens to Central Europe, a mythical place I had not visited yet except for the tantalizing glimpses offered by an illustrated Brothers Grimm book I had in my bedroom.

My familys strange red blanket ritual began in 1967, the inaugural year of Greeces military dictatorship. Deutsche Welle, the German international radio station that my parents were listening to, became our most precious ally against the crushing power of state propaganda at home: a window looking out to faraway democratic Europe. At the end of each of its hourlong special broadcasts on Greece, my parents and I would sit around the dining table while they mulled over the latest news.

Not understanding fully what they were talking about neither bored nor upset me. For I was gripped by a sense of excitement at the strangeness of our predicament: to find out what was happening in our very own Athens, we had to travel, through the airwaves, and veiled by a red blanket, to a place called Germany.

The reason for the red blanket was a grumpy old neighbor called Gregoris. Gregoris was known for his connections with the secret police and his penchant for spying on my parents; in particular my dad, whose left-wing past made him an excellent target for an ambitious, lowly snitch. After the coup dtat of April 21, 1967, brought neofascist colonels to power, tuning in to Deutsche Welle broadcasts became one of a long list of activities punishable by anything from harassment to torture. Having noticed Gregoris snooping around inside our backyard, my parents took no risks. And so it was that the red blanket became our defense from Gregoriss prying ears.

During the summers, my parents would use up their annual leave to escape the colonels Greece for a whole month. We would load up our black Morris and head north to Austria and southern Germany where, as my father kept saying during the interminable drive, Democrats can breathe. Willy Brandt, the German chancellor, and, a little later, Bruno Kreisky, his Austrian counterpart, were discussed as if they were family friends who also happened to be great protagonists in isolating our colonels and supporting Greek democrats.

The reception of the locals we encountered while holidaying in these German-speaking lands, away from the kitsch neofascist aesthetic of the colonels propaganda, was consistent with our conviction that we, as Greeks abroad, were bathed in genuine solidarity. And when our Morris would sadly putter back into Greece, past border crossings replete with photographs of our mad dictator and symbols of his crazy reign, the red blanket beckoned as our only refuge.

A HAND SHUNNED

Almost fifty years later, in February 2015, I made my first official visit to Berlin as Greeces finance minister. The Greek economy had collapsed beneath a mountain of debt, and Germany was its main creditor. I was there to discuss what to do about it. My first port of call was, of course, the Federal Ministry of Finance, to meet its incumbent leader, the legendary Dr. Wolfgang Schuble.

To him, and his minions, I was a nuisance. Our left-wing government had just been elected, defeating Dr. Schubles and Chancellor Angela Merkels allies in Greece, the New Democracy Party. Our electoral platform was, to say the least, an inconvenience for their Christian Democratic administration and their plans for keeping the eurozone in order. The elevator door opened up onto a long, cold corridor at the end of which awaited the great man in his famous wheelchair. As I approached, my extended hand was refused. Instead of a handshake, he rushed me purposefully into his office.

While my relations with Dr. Schuble warmed up in the months that followed, the shunned hand symbolized a great deal that was wrong with Europe. It was symbolic proof that in the half century separating my nights under the red blanket and that first meeting in Berlin, Europe had changed profoundly. How could my host even begin to imagine that I had arrived in his city with my head full of childhood memories in which Germany featured as my security blanket?

By 1974 the Greeks, with moral and political support from Germany, Austria, Sweden, Belgium, Holland and France, had overthrown totalitarianism. Six years after that, Greece joined the democratic union of European nations, to the delight of my parents, who could, at last, fold up the red blanket and put it away in the cupboard.

Less than a decade later, the Cold War had ended and Germany was reuniting in the hope of losing itself, in important ways, within a uniting Europe. Central to this project of embedding the new united Germany into a new united Europe was the ambitious program of a monetary union that would put the same money, the same banknotes and even the same coins (one side of which would be identical, no matter where it was issued) into every Europeans pocket. Make them use the same money, an Athenian taxi driver told me once in the early 1990s, and, before they know it, a United States of Europe will creep up on them.