Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

*Please note that some of the links referenced in this work are no longer active.

This book is dedicated to that American generation who honorably served in the Vietnam War. And this book salutes those who sacrificed. Their stories deserve to be known and their lives remembered.

The difficulty of this American generations war and the controversies it engendered made their willingness to serve, and the sacrifices that they made, the greater and not the lesser.

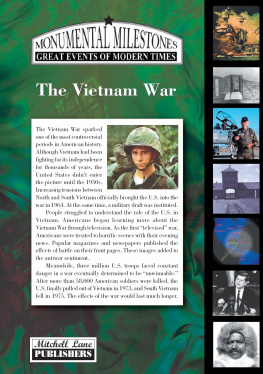

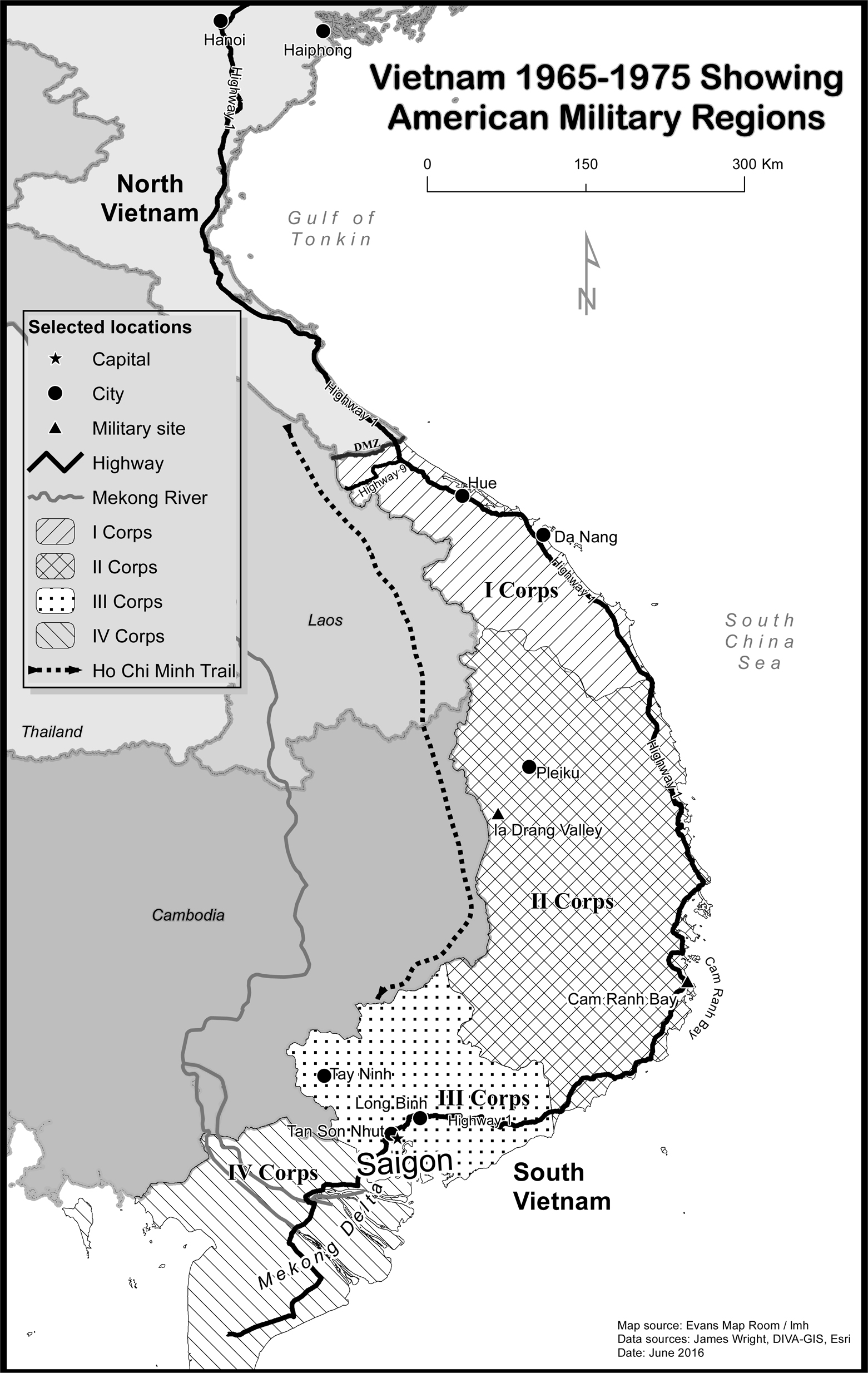

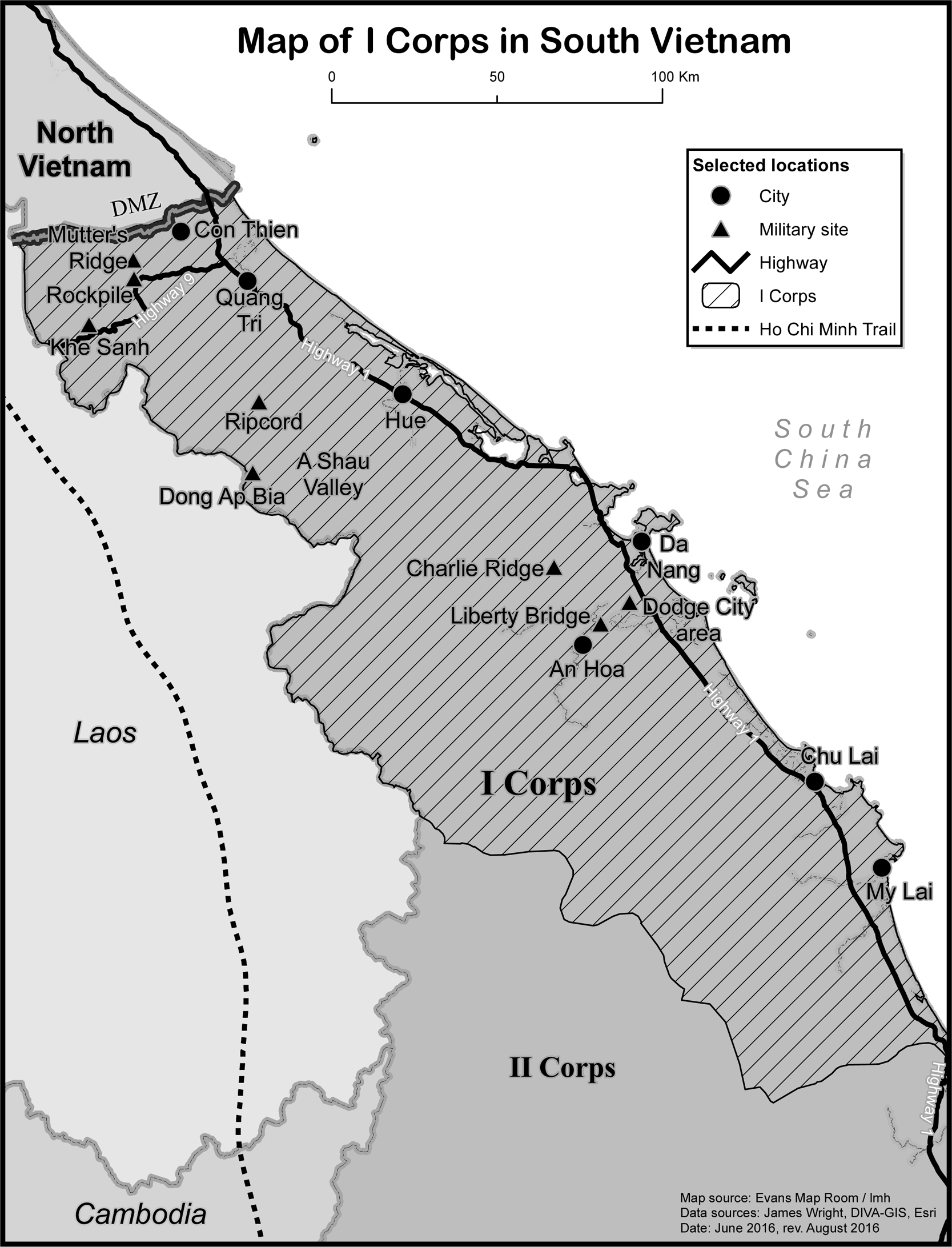

In early September 2014, I stood at the top of Dong Ap Bia in Vietnams A Shau Valley. Bordering Laos in the northwestern part of the old South Vietnam, this steep and imposing mountain was Hill 937 on U.S. military maps from the Vietnam War period. Local Montagnard tribesmen called it the Crouching Beast. The American soldiers who fought there knew it as Hamburger Hill.

For eleven days in May 1969, units of the 101st Airborne Division had fought North Vietnamese regulars, largely from the 29th Regiment but also the 6th and 9th Regiments, for control of this hill. Today there is a memorial at the top placed there in 2009 by the Socialist Republic of Vietnam celebrating a victorious place. Yet in fact it wasnt their victory, at least not then, not in that battle. The Americans prevailed, but the North Vietnamese returned. Six years later they would occupy Saigon and win the war.

I was on the hill forty-five years later because I was writing this book on the Vietnam War. I was part of a very small group that included two North Vietnamese Army (NVA) veterans of this 1969 battle. I had met them that morning in the nearby village of A Luoi, and they quickly accepted my invitation to join me in a climb of Dong Ap Bia. Our group also included an American army veteran who had served there at this time but not in this battle, as well as two young Vietnamese men. One was the son of a southern Vietnamese man who fought with the National Liberation Front (NLF), known as the Viet Cong, and the other the son of a soldier with the South Vietnamese Army, the Army of the Republic of Vietnam. The latter had spent some time in a reeducation camp after the war ended. I had been traveling through Vietnam battle sites because I wanted to see the places where Americans fought, especially in May and June 1969.

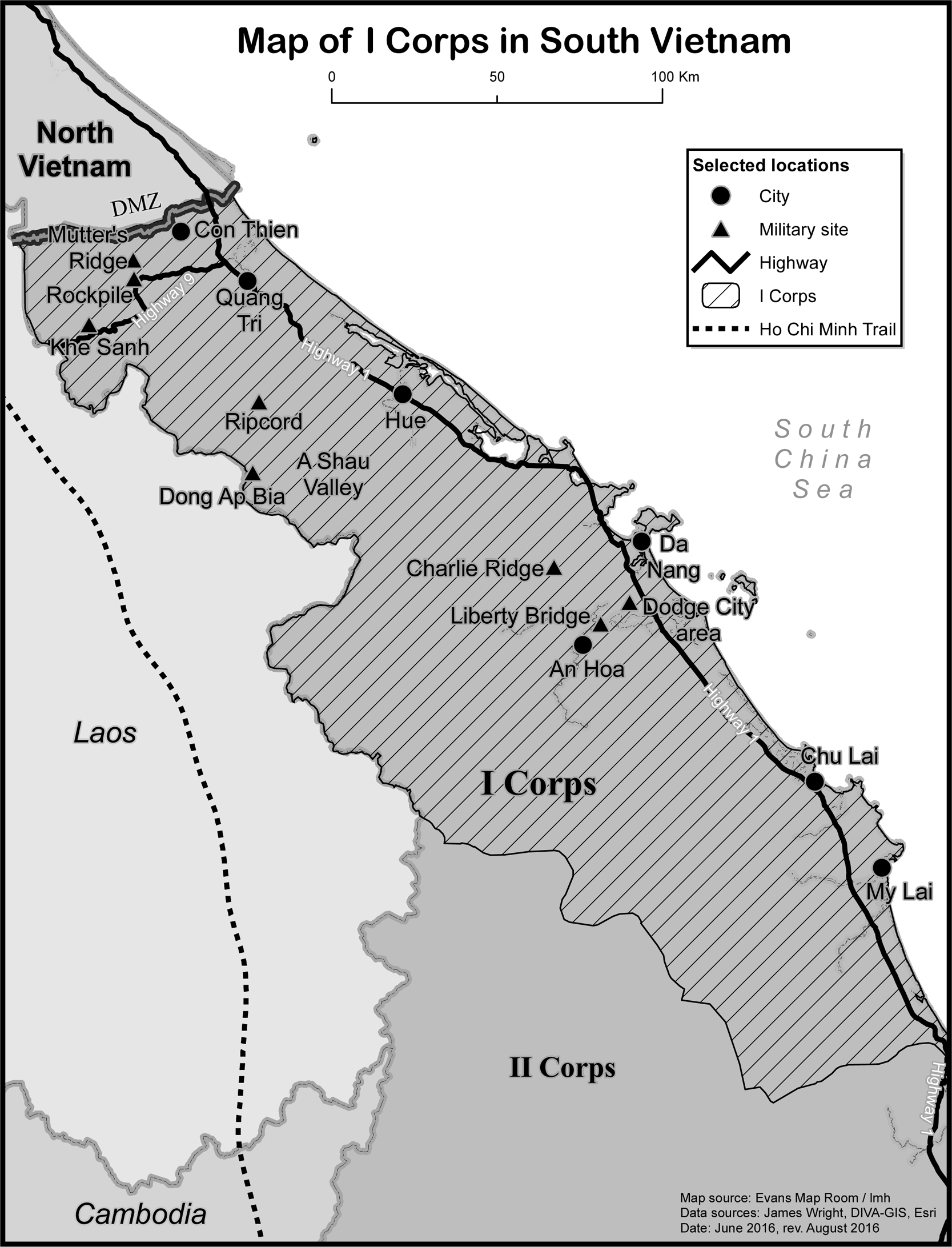

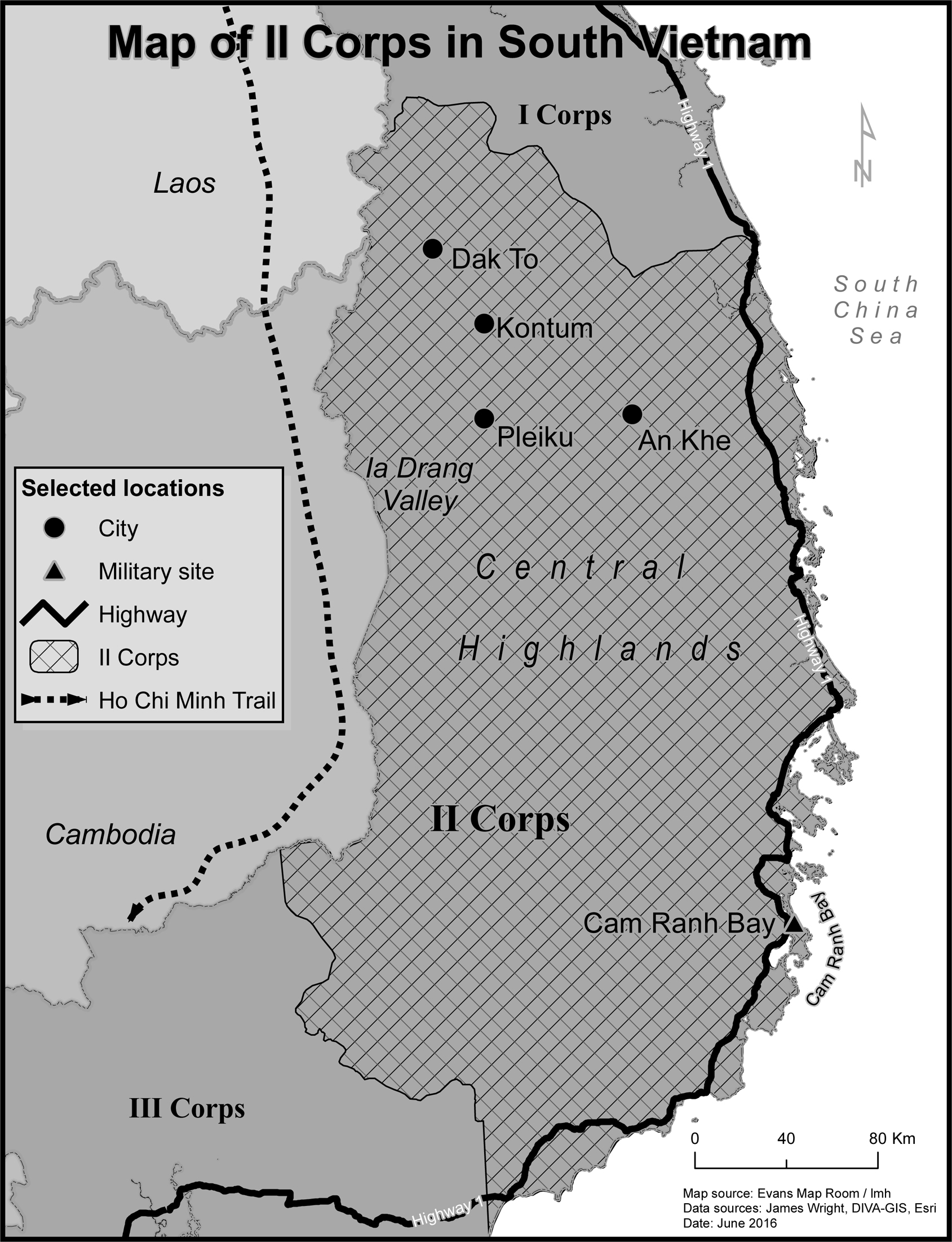

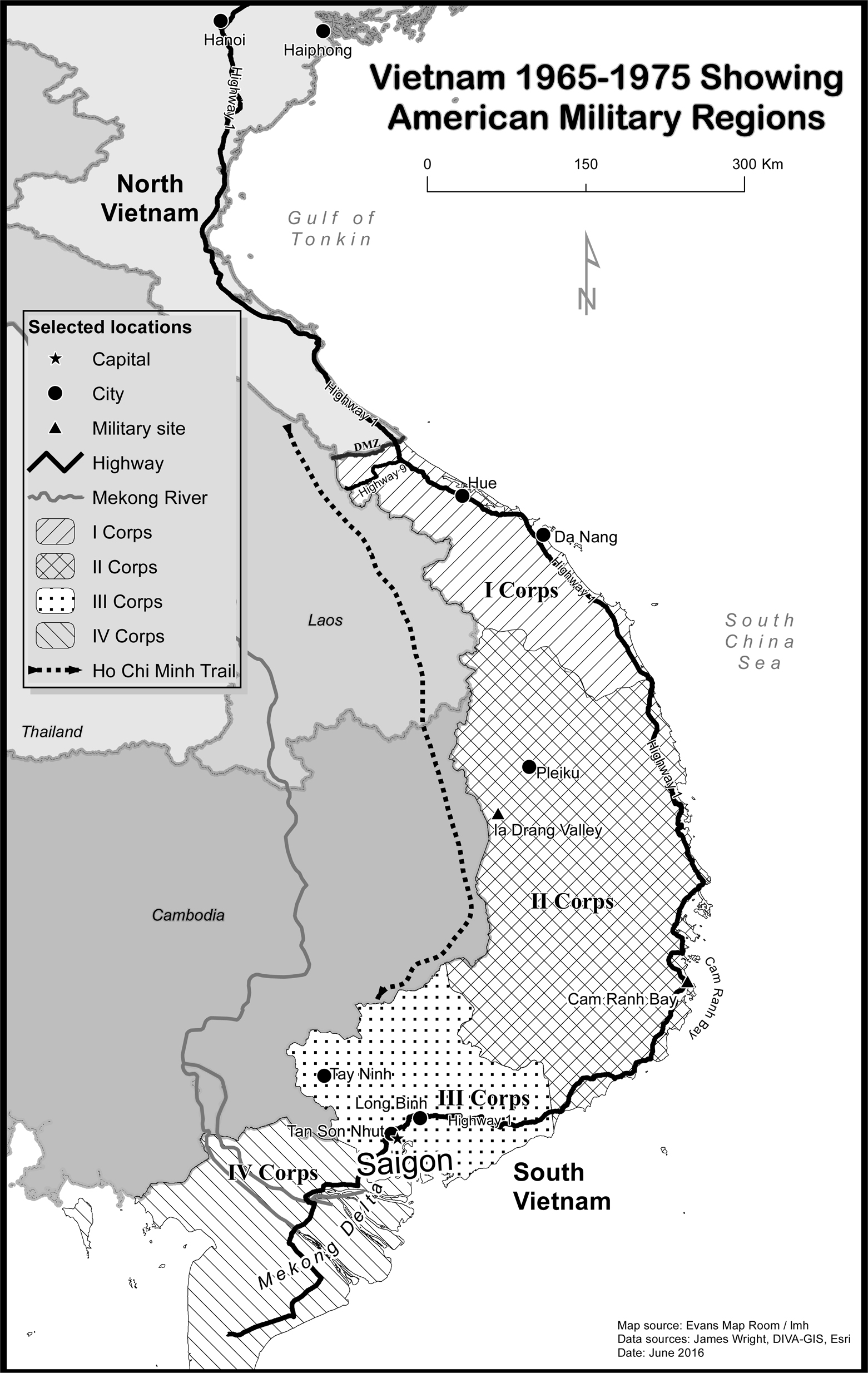

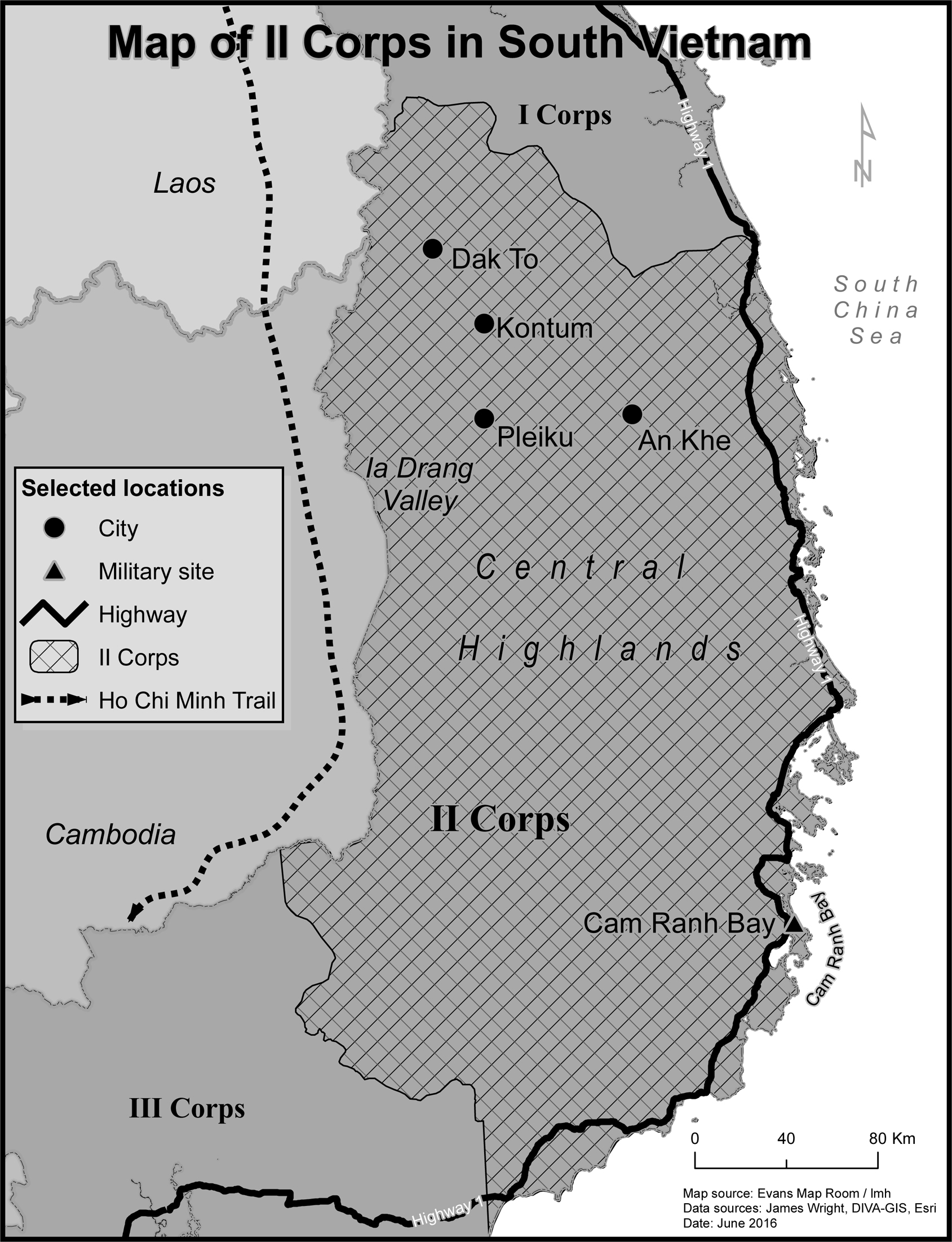

The contrasts between that distant war and modern Vietnam are everywhere. At Cu Chi, the extensive old tunnels are preserved as a tourist attraction, and there is a gruesome display of punji stick traps and other devices used against the Americans. The old airstrip at Dak To in the Highlands, where the 299th Engineers had fought against North Vietnamese forces based in Cambodia, is still desolate, barren, and deteriorating. The bunker where 9 American soldiers died had been filled and leveled, with manioc growing nearby and local farmers drying it on the old runway. Mutters Ridge up above Highway 9 continues to be a forbidding-looking place, in the midst of equally forbidding places, known by Americans who fought there as Razorback and the Rockpile.

Outside Hanoi, on the street adjacent to the lake where jagged fragments of a B-52 remain jutting from the water, is a restaurant called Cafe B52. In English, the sign promised that inside, in addition to coffee, Wi-Fi was available. And south of Da Nang, a cemetery is at the spot on the road where an army chaplain and 5 others died when their vehicle struck a mine in June 1969. This cemetery contains and celebrates the remains of National Liberation Front and North Vietnamese Army soldiers who died in the American War.

Southwest of Da Nang we spent some time in and near the area the marines called Dodge City. It indeed was a place filled with gunfights. South of Hill 55, I wanted to visit a rice paddy where Billy Smoyer was one of 19 marines in Kilo Company of the 3rd Battalion of the 7th Marines who died in an ambush on July 28, 1968. Billy was a star hockey and soccer player at Dartmouth who had joined the marines upon graduation. He came from a comfortable New Jersey family and probably could have deferred or even found an exemption from service. Instead, he said that the war shouldnt be fought only by the sons of miners and factory workers. I buried a Dartmouth hockey puck in the rice paddy where Second Lieutenant Smoyer died less than four weeks after arriving in Vietnam.

In a tragic coincidence, a Dartmouth classmate and friend of Billy Smoyerss, Duncan Sleigh, died in another ambush less than five months later just two miles away. Duncan was in Mike Company of the 3rd Battalion of the 7th Marines. They lost 14 men in that ambush and Second Lieutenant Sleigh was awarded the Navy Cross posthumously for his effort to shield a wounded marine from another grenade. The marine survived but Sleigh did not. I buried a small New Hampshire memento in that rice paddy.

North of the pilings from the old Liberty Bridge, four of us were looking across a field at the slope where several U.S. marines died on May 29, 1969, on the last day of Operation Oklahoma Hills. A smiling teenage Vietnamese boy stepped out of a house and waved to us. Then his grandfather came out and greeted us and invited us in for tea. He had lived in that house for his entire eighty-five years. He served during the war with a local NLF unit. He told us that in the 1960s, during the day he farmed and at night he fought. Looking out from this home, looming above this peaceful place, remained the heavy and dark green hills that Americans called Charlie Ridge. The U.S. troops seldom went there and never stayed long. As we walked along the pathway from the home of this veteran, we passed a group of young children playing. They smiled and shouted proudly in English, Hello! And one flashed the common V fingers greeting, ironically evoking the American antiwar peace sign.

But Dong Ap Bia has remained Hamburger Hillvery steep, more than three thousand feet high, red clay and rocks, slippery after a summer shower that began our trek. Jungle heat and humidity slowed our pace. Modern Vietnam has hardly touched this place. After the 1969 battle, soldiers described the hill as looking like a moonscapeartillery and bombs and herbicides having torn and burned trees and undergrowth. The land, at least superficially, had now recovered. Double- and triple-canopy growth had returned, with incredibly dense foliage and shrubs, much of which would have been familiar to those men of the 187th of the 101st Airborne who hurried from their helicopters there on May 10. Now the Crouching Beast was silent, or at least the chaotic sounds of war had been replaced by a cacophony from unfamiliar birds and animals and insects.