Mandela

IN CELEBRATION OF A GREAT LIFE

Mandela and his wife Graa Machel wave to crowds at the 46664 AIDS benefit concert in Cape Town in 2003.

For Matthew, Leila, Morne and Gabriella Ruby

Mandela at the 2007 unveiling ceremony of a bronze statue in his honour at Londons Parliament Square.

Mandela

IN CELEBRATION OF A GREAT LIFE

Charlene Smith

Foreword by Archbishop Desmond Tutu

Published by Struik Travel & Heritage

(an imprint of Random House Struik (Pty) Ltd)

Company Reg. No. 1966/003153/07

Wembley Square, First Floor, Solan Road, Gardens, Cape Town, 8001, South Africa

PO Box 1144, Cape Town, 8000, South Africa

Copyright in published edition: Random House Struik 2012

Copyright in text: Charlene Smith 2012

Copyright in photographs: see credits on page , 2012

Publisher: Claudia Dos Santos

Managing editor: Roelien Theron

Editor: Leah van Deventer

Co-editor: Charlene Smith

Designer: Catherine Coetzer

Picture researcher: Colette Stott

Project coordinator: Alana Bolligelo

Indexer: Joy Clack

Proofreader: Alfred LeMaitre

Reproduction by Hirt & Carter Cape (Pty) Ltd

ISBN 978 1 43170 079 0 (Print)

ISBN 978 1 43170 238 1 (ePub)

ISBN 978 1 43170 239 8 (PDF)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval

system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the

publishers and the copyright holder(s).

Get regular updates and news by subscribing to our newsletter at

www.randomstruik.co.za

PUBLISHERS NOTES

- Where no reliable sources could be found, names have been omitted.

- The opinions expressed in this book are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the publisher.

- The terms black and African refer to all people that were not born with white skins. However, in this book, to explain certain peculiarities of laws or events, or in quoting sources directly, the terms coloured and Indian are on occasion used.

- Every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyrighted material and to seek their permission for the use thereof. The publisher apologises for any inadvertent omissions and would be grateful if notified of any corrections, which shall be included in future reprints and editions of the book.

- Please email any comments or updates to:

Mandela stands with Britains Prince Richard, the Duke of Gloucester, at his investiture as a Bailiff Grand Cross of the Order of St John, in London, 2004.

Foreword

IN JULY 1988, two years before Nelson Mandela walked a free man from Victor Verster Prison, Archbishop Trevor Huddleston suggested, in his role as the President of the Anti-Apartheid Movement, that the world should celebrate Mandelas 70th birthday in prison. Many thousands of young people especially, although not exclusively, responded enthusiastically to his call to make this the mother of all birthday celebrations. People of all ages went on pilgrimage from all the corners of the United Kingdom and then they gathered at Hyde Park Corner in London, an enormous sea of faces. They congregated there, 250,000 of them, and the vast majority were young people.

His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama greets Archbishop Desmond Tutu in Vancouver, 2004.

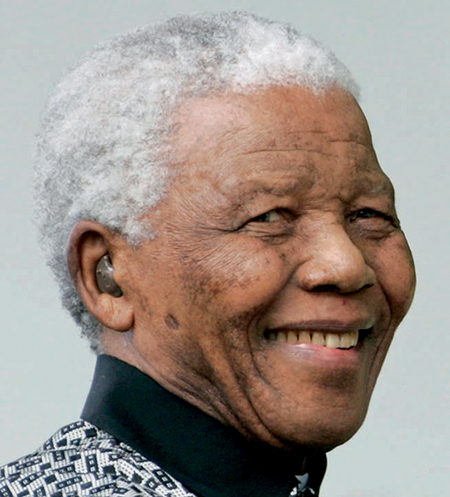

What struck me forcibly, as I gazed over them, was that most of them had not even been born when Madiba was sentenced to life imprisonment in 1963, and they had not seen him since; they had not heard from him, but they had certainly heard about him from others. The point is that they had no direct knowledge of him and, since pictures of prisoners were not permitted, they did not know what he really looked like even now. And yet here they were paying tribute to a prisoner, yes a prisoner, of conscience whom the British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher (of the time) had disdainfully dismissed as a terrorist.

What an extraordinary phenomenon that he was able to move people so deeply without saying anything, without doing anything. Some of us worried that they might be in for an enormous disillusionment, that they would discover that their idol had feet of clay. Perhaps it would be better that he should remain incarcerated, out of sight, because distance did indeed lend enchantment to the view. In prison he was serving a splendid purpose because he was giving focus to the struggle, personalising it in that way so essential for causes if they were to galvanise the kind of popular support that the largely indifferent Reagan White House and Thatcher 10 Downing Street would find difficult to ignore. Outside prison he would be found to be less effective because he would be so human, so vulnerable, so disappointing to those who had placed him on a pedestal of near sainthood and infallibility.

Yes, we were all in the seventh heaven of delight on 11 February 1990, when he walked out of Victor Verster prison side by side with Winnie. It was an unforgettable day, but there were butterflies in the pit of the stomach would he measure up to all that people believed and hoped about him? Would we not all come crashing to the ground after all the euphoria? The world joined us in welcoming the worlds most famous prisoner, but for how long would they pay attention when they are so notoriously fickle? Was he but a few days wonder, and would they flit off to the next attraction to land in their spotlight?

The man is a phenomenon, in a class by himself, for the frenzy of media attention has not abated. If anything, it has increased. Far from being a huge disillusionment, he has not ceased to amaze everyone. A deeply divided land, alienated by long years of repression and injustice, and at variance on most subjects, is unanimous about one thing: that this former terrorist, so frequently vilified and hated, is today our greatest asset.

He is loved by virtually all South Africans, even the most virulent critics of his African National Congress-led government. He is the most popular political leader in the land, almost beyond criticism. Who will easily forget the scenes at Ellis Park when he walked onto the turf wearing Franois Pienaars No. 6 on his Springbok jersey on the day of the final for the Rugby World Cup in 1995, when an overwhelmingly white crowd, mostly Afrikaners, broke out in reverberating chants: Nelson, Nelson, Nelson. He has the knack of doing the right thing, which with some political leaders would be contrived or gauche. With him it turns out to be exactly what touches responsive chords in the people. He has bowled South Africans, and indeed the world, over with his extraordinary magnanimity, his readiness and eagerness to forgive. He invited the widows of former South African political leaders of all persuasions and races to a tea party at the Presidency and charmed them. He stole the hearts of many Afrikaners, whom he had already attracted by supporting the Springbok emblem for rugby, by going to visit the widow of Dr Verwoerd in her Afrikaner exclusivist stronghold Orania. Here he was having tea, at some inconvenience to himself, with the widow of the architect and high priest of apartheid. Unbelievable! He later had a meal with Dr Percy Yutar, the man who had prosecuted in the Rivonia Trial and who many believed had gone well beyond the accepted conventions in passionately demanding the death sentence for the accused (of whom he was one). His magnanimity knows no bounds. He was ready to have accompanied Mr PW Botha to appear before the TRC as subpoenaed, if it would help Mr Botha not feel humiliated.

Next page