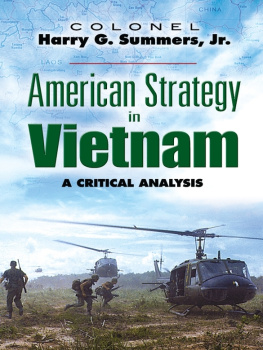

Colonel Harry G. Summers, a veteran soldier who through personal experience knows the bayonet point reality of war but who also, in this book, demonstrates a capacity for careful research and scholarly analysis [On Strategy is] a worthwhile contribution toward illuminating a part of American history which, though recent, is clouded and distorted by misunderstanding and emotion.

Gen. Hamilton H. Howze, USA (Ret.)

The most thorough and devastating analysis of the impact of theorizing intellectuals of all kinds on the US military machine and its concept of itself and war.

Correlli Barnett, RUSI, Journal of the Royal

United Services Institute for Defense Studies

Heads the list of required reading for todays and tomorrows Army leaders at all levels of command and staff could be the most important analytical military literature produced by a member of our armed forces.

Gen. Andrew P.OMeara, USA (Ret.), ARMOR Magazine

I have now read your study of the Vietnam war with very great interest and admiration your application of Clausewitzs principles seems to me highly perceptive and of the greatest possible value. In particular, your use of his distinction between preparation for war and war proper appears to me to provide a conceptual framework which deserves the widest possible publicity.

Michael Howard

Superb From [On Strategy], we must begin a useful professional dialogue about Vietnams lessons in the context of todays and tomorrows world environment. This is must reading!

Gen. Donn A. Starry, USA (Ret.), Military Review

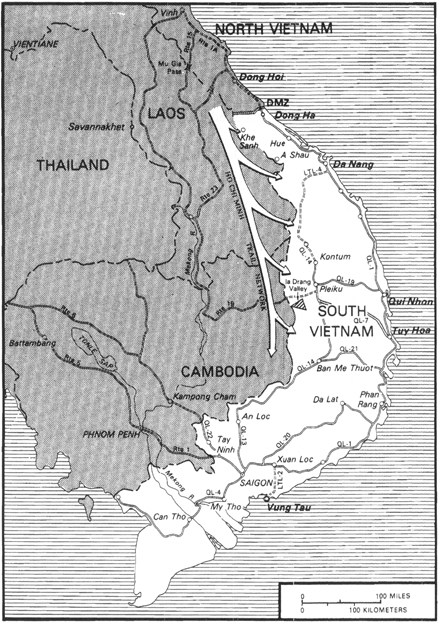

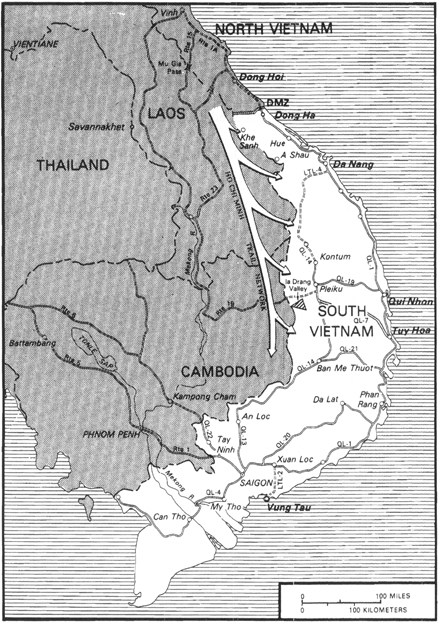

Adapted from Map 6, Vietnam from Cease-Fire to Capitulation by Colonel William E. LeGro, USA. Washington, U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1981, p. 37.

A Presidio Press Book

Published by The Random House Publishing Group

Introduction, epilogue and revisions to basic text

copyright 1982 by Presidio Press

This edition printed 1995

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Presidio Press, an imprint of The

Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc.,

New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of

Canada Limited, Toronto.

Presidio Press and colophon are trademarks of Random House, Inc.

www.presidiopress.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Summers, Harry G.

On strategy.

Bibliography:

1. Vietnamese Conflict, 1961-1975United States. 2.Strategy. I. Title.

DS558.2.S95 1982 959.7043373 82-7498

eISBN: 978-0-307-55876-3 (QPB) AACR2

v3.1

Contents

Foreword

First issued as On Strategy: The Vietnam War in Context at the Army War College in 1981, the study was not intended to be a history of the Vietnam War. As Army War College commandant Major General Jack N. Merritt noted, It is not a detailed account of day-to-day tactical operations or an examination of the many controversies of the war. What was intended was a narrow focus on the war in the areas of major concern to the Army War Collegethe application of military science to the national defense.

It was to have an impact beyond anyones expectations. Approved for publication by then Army Chief of Staff General Edward Shy Meyer, who sent copies to all army active and retired three- and four-star generals, copies were also sent to all members of the House and Senate by a then relatively unknown congressman, Newt Gingrich of Georgia, now speaker of the House, who at the time was active in the military reform movement.

Particularly gratifying, however, was the books validation by those who had fought the war, the military students at the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps War and Staff Colleges, where the book was used as a teaching text. In the early 1980s, almost all these students were Vietnam combat veterans who could and did evaluate the work in terms of their own personal battlefield experiences.

But the most unexpected aspect was the reception from outside the military. Drew Middleton, the renowned military correspondent for The New York Times, called it just about the best thing I have read on Vietnam, a comment that prompted the books commercial publication in 1982 under its present title. On Strategy was adopted as a teaching text by many civilian colleges and universities. The book became so central to the teaching of the Vietnam War that in April 1995, the Center for Study of the Vietnam War at Texas Tech University held a symposium, Winning and Losing: A Reexamination of the Summers Thesis and the Vietnam War. Most historians, said a news account of the conference, agreed with the main point in Summerss thesis explaining why the United States lost the war.

One of the anomalies of the Vietnam War is that until recently most of the literature and almost all the thinking about the war ended with the Tet Offensive of 1968. As a result, the common knowledge was that America had lost a guerrilla war in Asia, a loss caused by failure to appreciate the nuances of counterinsurgency war.

But the truth was that the war continued for seven years after the Tet Offensive, and that latter phase had almost nothing to do with counterinsurgency or guerrilla war. The threat came from the North Vietnamese regular forces in the hinterlands.

The final North Vietnamese blitzkrieg in April 1975 had more to do with the fall of France in 1940 than it did with guerrilla war. In fact, the North Vietnamese commander, Senior General Tran Van Dung, does not even mention the role of the Viet Cong in his account of his Great Spring Victory.

As former CIA director William Colby noted in his book Lost Victory, Saigon did not fall to barefoot black-pajama-clad guerrillas. It fell to a 130,000-man 18-division invasion force supported by tank and artillery. Thus it was apparent to me when I began my analysis of the war in 1979 that the key to understanding our failure did not lie in counterinsurgency theory, but in the long-since-discarded theories of conventional war.

As Colby stated, the U.S., without even noticing, had won the peoples war. One reason it didnt notice is that Washington was more concerned with signaling than with war fighting. Corroborating my findings on the neglect of conventional war doctrines, Harvard Universitys Stephen Peter Rosen examined the war in the terms of limited war theory. His 1982 analysis found two major reasons for our failure in Vietnam.

As is explored in depth in On Strategy, first was the failure to factor the American people into the strategic equation. Political scientist Robert Osgood, among the most influential of the limited-war theorists, concluded that even though the American people will be hostile, because of their traditions and ideology, to the kind of strategy he proposes, that strategy must still be adopted.

Second, as is also explored in On Strategy from a somewhat different perspective, was the refusal to see Vietnam as a war. As Rosen explains, we had adopted a limited war signaling strategy. It was conceived by such academic limited-war theorists as Robert Osgood and Thomas Schelling, who shared the happy belief that the study of limited war in no way depended on any actual knowledge about war. According to Osgood, military problems are no proper part of a theory of limited war because limited war is an essentially diplomatic instrument, a tool for bargaining with the enemy. Military forces are not for fighting but for signaling.