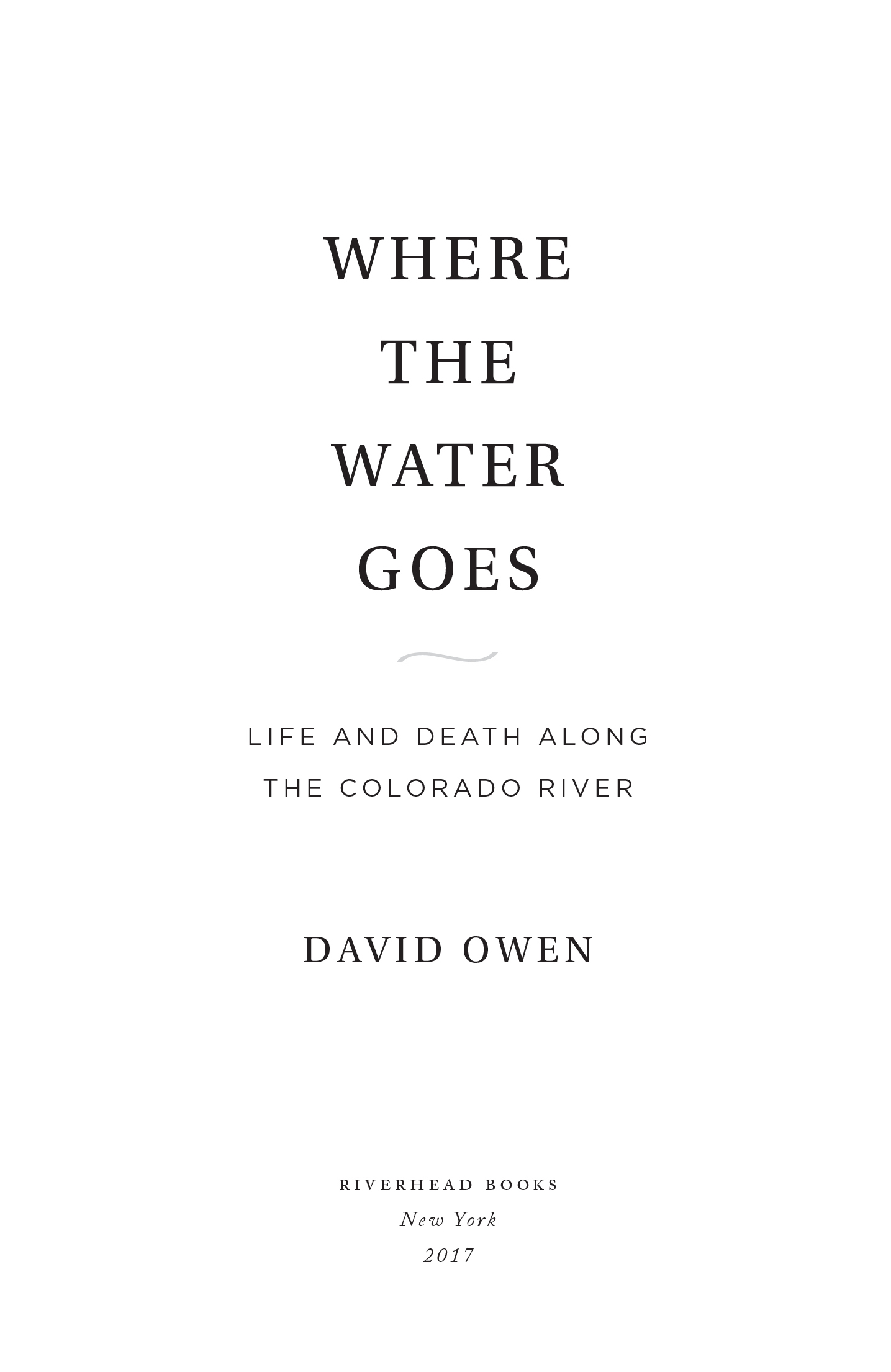

David Owen - Where the Water Goes

Here you can read online David Owen - Where the Water Goes full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2017, publisher: Penguin Publishing Group, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Where the Water Goes

- Author:

- Publisher:Penguin Publishing Group

- Genre:

- Year:2017

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Where the Water Goes: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Where the Water Goes" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Where the Water Goes — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Where the Water Goes" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The Conundrum

Green Metropolis

Sheetrock & Shellac

Copies in Seconds

The First National Bank of Dad

Hit & Hope

The Chosen One

The Making of the Masters

Around the House (also published as Life Under a Leaky Roof)

Lure of the Links (coeditor)

My Usual Game

The Walls Around Us

The Man Who Invented SaturdayMorning

None of the Above

High School

RIVERHEAD BOOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

Copyright 2017 by David Owen

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Parts of several chapters of this book first appeared, in different form, in The New Yorker.

Some material about Las Vegas first appeared, in different form, in Golf Digest.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Owen, David, date.

Title: Where the water goes : life and death along the Colorado River / David Owen.

Description: New York : Riverhead Books, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016039410 | ISBN 9781594633775 | ISBN 9780698189904 (e-ISBN)

Subjects: LCSH: Colorado River (Colo.Mexico)Description and travel. | Colorado River (Colo.Mexico)Environmental conditions. | Owen, David TravelColorado River (Colo.Mexico) | Water-supplyWest (U.S.) | Stream ecologyColorado River (Colo.Mexico)

Classification: LCC F788 .O84 2017 | DDC 917.91/304dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016039410

p. cm.

Map by Sarah Evans Lloyd. Reference: Pacific Institute, Oakland, California

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate Internet addresses at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Version_1

For Alice and Hugh OKeefe

O ur pilot, David Kunkel, asked me to retrieve his oxygen bottle from under my seat, and when I handed it to him he gripped the plastic breathing tube with his teeth and opened the valve. We had taken off from Boulder not long before and were flying over Rocky Mountain National Park, thirty miles to the northwest. Kunkel was navigating with the help of an iPad Mini, which was resting on his legs. People dont usually think altitude is affecting them, he said. But if you ask them to count backward from a hundred by sevens they have trouble. What struck me at that moment was not how high we were but how low: a little earlier, we had flown within what seemed like hailing distance of the sheer east face of Longs Peak, and now, as Kunkel banked steeply to the right to give us a better view of a stream at the bottom of a narrow valley, his wingtip appeared to pass just feet from the jagged declivity beneath us. Snow had fallen in the mountains during the night, and I half expected it to swirl up in our wake.

The other passenger, sitting in the copilots seat and leaning out the window with a big camera, was Jennifer Pitt, who at the time was a senior researcher for the Environmental Defense Fund. Pitt is in her forties. She has long brown hair, which she had pulled back into a ponytail, and she was wearing a purple fleece. She worked at the EDF, mostly on issues related to the Colorado River, from 1999 till 2015, when she moved to a similar job at the National Audubon Society. In recent years, her focus has been on the rivers other end, in Mexico, but she had agreed to show me its source. Our principal destination that day was the Colorados headwaters, just over the Continental Divide, roughly fifty miles south of the Wyoming state line. The best way to see a river system is from the air, shed told me earlier. She arranged our flight through LightHawk, an international nonprofit organization that supplies volunteer pilots and their airplanes, at no charge, for a variety of environmental purposes. The previous day, a LightHawk pilot had flown twenty black-footed ferrets from Fort Collins to a spot near the Grand Canyon, for relocation.

Before our flight, I looked up Kunkel on Google and was disconcerted to find a news story about him landing his Cessna 340 on a highway in the Rockies after losing both engines in succession. But then I realized that nothing like that could happen to us, because the plane hed be using for our trip, a Maule M-7, had just one engine. I looked up Pitt, too. She was born in Boston and grew up in Westchester County, New York, in a suburb of New York City. I think you can trace my interest in rivers back to my childhood in Westchester, she told me later, because I grew up in a river town, on the Hudson, and when I was a kid Pete Seeger came to my school and sang to me about rivers. As an undergraduate, at Harvard, she majored in American history and literature, but developed an interest in urban planning and landscape architecture. After graduation, she continued, I worked in Manhattan for a year, for the Department of Parks and Recreation, and realized that that was not what I wanted to do. She got a job as an interpretive ranger in Mesa Verde National Park, in southwestern Colorado, and that experience, she said, gave another twist to my view of the world, and how an ancient culture used the resources around them. She earned a masters degree in environmental sciences, with a focus on water, at the Yale School of Forestry, then worked in Washington, D.C., for five years, mostly at the National Park Service. In 1999, the Environmental Defense Fund hired her to create programs related to the Colorado River and the ecosystems that depend on it. In 2003, she married Michael Cohen, a senior associate at the Pacific Institute, another environmental organization. (They met at a water conference in Tucson.) They live in Boulder and have a daughter.

Kunkel dipped a wing, and Pitt pointed toward the Never Summer Mountains, on our right. Theres the Grand Ditch, she said. I saw what looked like a road or a hiking trail cut across the face of a steeply sloping forest of snow-dusted conifers; she explained that it was an aqueduct, dating to 1890. Its original full name was the North Grand River Ditch. (Until 1921, the section of the Colorado thats upstream from its confluence with the Green, in eastern Utah, was called the Grand. Hence: Grand Lake, Grand Junction, Grand Valleybut not Grand Canyon, which was named for its grandness.) It was built with pickaxes and black powder, mostly by Japanese laborers, and it operates by gravityan impressive feat of pre-laser engineering. The Grand Ditch is fourteen miles long, and much of it is above ten thousand feet. It carries water across the Continental Divide at La Poudre Pass and empties it into a stream that flows toward the states eastern plains, where even by the late 1800s farmers were feeling parched. It doesnt tap the Colorado directly, but captures as much as forty percent of the flow from slopes that would otherwise feed it, like a sap-gathering gash in the trunk of a rubber tree. We had already flown over several larger, more recent additions to the same network: Long Draw Reservoir, completed in 1930; Estes Lake, which serves as a trans-basin junction box; and five connected natural and man-made lakes that lie on the western side of the divide and gather and store water from the Colorado or its watershed. The northernmost of the lakes spills as much as a third of a billion gallons a day into the Alva B. Adams Tunnel, which was built in the 1940s. Adams was a lawyer and a U.S. senator, and in the early 1930s he served as the chairman of the Committee on Irrigation and Reclamation. The tunnel moves the water under the center of the park, drops it through five hydroelectric generating plants, and delivers it to a distribution system that serves a populous area east of the mountains, including Boulder. The main elements of the system are known collectively as the Colorado-Big Thompson Project. (In the West, project almost always means dam, reservoir, aqueduct, canal, or all four.)

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Where the Water Goes»

Look at similar books to Where the Water Goes. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Where the Water Goes and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.