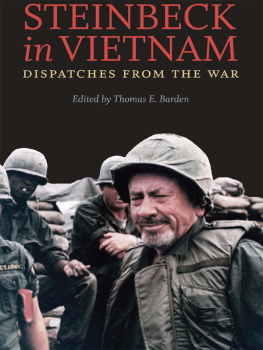

STEINBECK in VIETNAM

University of Virginia Press

2012 by the Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

First published 2012

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Steinbeck, John, 19021968.

[Selections. 2012]

Steinbeck in Vietnam : dispatches from the war / John Steinbeck ; edited by Thomas E. Barden.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8139-3257-6 (cloth : acid-free paper)

1. Steinbeck, John, 19021968Political and social views. 2. Vietnam War, 19611975Literature and the war. I. Barden, Thomas E. II. Title.

PS3537.T3234A6 2012

959.7043373dc23

2011026049

Vietnam War: No Front, No Rear, Action in the Delta, Terrorism, and Puff, the Magic Dragon, from America and Americans and Selected Nonfiction by John Steinbeck, edited by Susan Shillinglaw and J. Benson, 2002 by Elaine Steinbeck and Thomas Steinbeck. Used by permission of Viking Penguin, a division of Penguin Group (USA), Inc.

All other columns 1965, 1966, 1967 by John Steinbeck; renewed 1993, 1994, 1995 by Elaine Steinbeck and Thomas Steinbeck. Reprinted with permission of McIntosh & Otis, Inc.

TITLE PAGE Steinbeck in the door gunner seat of a UH-1 Huey helicopter wearing a headset to communicate with the pilot. MARTHA HEASLEY COX CENTER, SAM GIPSON JR. BEQUEST . 1-538

CONTENTS

PREFACE

W HEN I MENTION that John Steinbeck went to Vietnam in the 1960s to cover the war as a roving newspaper reporter, most people respond with genuine surprise. Those who came of age after that turbulent time, along with many who lived through it and even some who were in Vietnam themselves, are usually unaware that Steinbeck was deeply and personally involved. Although his career continued for almost three decades after the 1939 publication of The Grapes of Wrath, he is still most closely associated with his Depression-era works of social struggle. But from Pearl Harbor on, he often wrote about Americas wars from first-hand experience, and Vietnam was no exception.

Between December 1966 and May 1967 the sixty-four-year-old Steinbeck traveled throughout Southeast Asia, posting dispatches from South Vietnam, Thailand, Laos, and Indonesia as a war correspondent for the Long Island daily newspaper Newsday. This book makes all of those dispatches available for the first time since their publication over forty years ago.

The quarrels of those days are history now, but from a twenty-first century vantage point, it is easy to see how these essays, in which Steinbeck made his best argument for the necessity of the war and the Johnson Administrations execution of it, must have infuriated the doves and delighted the hawks of the late 1960s. But it is also interesting to consider from this distance how important the essays must have been to the large number of readers who were undecided and bewildered about the war and who considered John Steinbeck a reliable moral witness. He was an American voice readers had known and respected for decades. And unlike most of the other pundits and writers who were taking sides on Vietnam, he was actually willing to go to the combat zones and put himself in harms way. His Vietnam essays offered his fellow Americans personalized accounts from a war that was splitting the country into increasingly angry factions and defying comprehension, much less resolution.

But these dispatches are significant beyond their value as historical documents. Even though they were written on the fly in hotel rooms and were often little more than field notes with off-hand political opinions thrown in, many of them still have the spell-casting power of Steinbecks great works of fiction. They have immediacy and they have passion. And they are, after all, the last published writings of an American author of enduring national and international stature. It is important that Nobel laureate John Ernst Steinbecks entire body of written work be available in print.

The introduction will provide basic background information and situate the dispatches in the context of Steinbecks personal and writing life at the time. The tasks of analyzing, critiquing, and assessing the essays I have saved for an afterword. I want to avoid pressing my own ideas about the dispatches onto readers before they have had a chance to read them for themselves. I have also placed the individual notes on each essay at the back of the book to lighten the weight of annotation as readers encounter Steinbecks original words.

There are some people and institutions I want to thankthe University of Toledo for giving me a sabbatical in the spring of 2010 to complete the research; the Princeton University Library staff for emailing me relevant portions of the Preston Beyer John Steinbeck collection; the staff of the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies at San Jose State University, especially Paul Douglass and Sstoz Tes, for their informed answers to my endless questions; the Manuscripts Division people at the Library of Congress; and the staff at the Pierpont Morgan Library.

My University of Toledo colleagues Jim Campbell and Joel Lipman helped me figure out how to tell this story, and fellow Steinbeck scholars Rich Hart and Michael Meyer helped me tell it better. Robert Harmon, Professor Emeritus of Library Science at San Jose State University, who worked this territory before me, was generous in sharing his knowledge. Llew Gibbons, my UT College of Law colleague, gave me good advice about copyright and permissions issues. Florence Eichen at Penguin Group and Rebecca Strauss at McIntosh and Otis were both very helpful in guiding me through the intricate process of gaining permission to reprint Steinbecks work. Cathie Brettschneider, the humanities editor at the University of Virginia Press, helped tremendously by championing this book from the beginning. And Morgan Myers, a project editor at the Press, gave the manuscript the tender, loving care of a true Steinbeck fan.

Joshua Mooney, my undergraduate research student, became a Steinbeck scholar in the course of our work together; in fact, he won the Louis Owen Award for Steinbeck Scholarship in 2009. Sean Odoms, University of Toledo student worker and keyboarder extraordinaire, provided good clerical support. My son Zacharias Barden, whose high writing standards make me proud, helped me fix many awkward sentences. And most of all, I thank Rayna Zacharias, my wife, music partner, dear companion, and intrepid research associate, for her knack for making research, and life in general, a great adventure.

Portions of the introduction appeared previously in Steinbeck Review (vol. 5, no. 2, Spring 2008) as an essay titled Steinbeck in Vietnam. Used with permission.

INTRODUCTION

A S EVERYONE KNOWS, John Steinbeck gained national prominence in the 1930s for books that focused on the plight of migrant workers, displaced Okies, political radicals, and the downtrodden in general. His novels In Dubious Battle (1936), Of Mice and Men (1937), and The Grapes of Wrath (1939) gained him a huge reading audience. They also gained him a reputation with conservatives, including some in the federal government and the military, as an extremist subversivea dangerous figure. While Steinbeck was never formally investigated, the FBI kept a dossier on him, starting in the early 1940s (FBI Report #100-106224), that documented his political activities, his personal connections, and his writings. The army intelligence service, on the other hand, did formally investigate him in 1943 and filed a report (G-2 File: IX-O/S-1403c) that concluded, In view of substantial doubt as to subjects loyalty and discretion, it is recommended that subject not be considered favorably for a commission in the Army of the United States. Thus, while he was in personal touch with, and personally advising, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Steinbeck was not allowed to join the army, even though he tried several times. His association with elements of the Communist Party, as the FBI dossier put it, and the fact that some of his writings appeared in Communist publications, were the bases for the army intelligence services conclusion.

Next page