BEYOND THE SPECTACLE

OF TERRORISM

THE RADICAL IMAGINATION SERIES

Edited by Henry A. Giroux and Stanley Aronowitz

Now Available

Beyond the Spectacle of Terrorism: Global Uncertainty and the Challenge of the New Media

by Henry A. Giroux

Forthcoming

A Future for the American Left

by Stanley Aronowitz

Afromodernity: How Europe Is Evolving toward Africa

by Jean Comaroff and John L. Comaroff

BEYOND THE SPECTACLE OF

TERRORISM

Global Uncertainty and the

Challenge of the New Media

HENRY A. GIROUX

First published 2006 by Paradigm Publishers

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon 0X14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2006 by Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Giroux, Henry A.

Beyond the spectacle of terrorism : global uncertainty and the challenge of the new media / Henry A. Giroux.

p. cm. (Radical imagination)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 1-59451-239-6 (hc) ISBN 1-59451-240-X (pbk) 1. Terrorism. 2. Democracy. 3. Internet. 4. Reality television programs. I. Title.

II.

Series.

HV6431.G547 2006

303.625dc22

2005033050

Designed and Typeset by Straight Creek Bookmakers.

ISBN 13: 978-1-59451-240-7 (pbk)

ISBN 13: 978-1-59451-239-1 (hbk)

To Susan, who has given me a life I would never have imagined.

I want to thank Susan Searls Giroux, John Comaroff, Roger Simon, Arif Dirlik, David Theo Goldberg, Stanley Aronowitz, Lawrence Grossberg, and Nick Couldry for providing me with a number of critical insights and suggestions that otherwise would not have been in this paper. While I am solely responsible for the paper, their critical input was invaluable in helping me think through the various ideas I take up in this piece. I also want to thank Nasrin Rahimieh, Ken Saltman, and Max Haiven for their critical input. I am deeply indebted to my graduate assistant, Grace Pollock, who brought all of her creative and critical editorial skills to bear on this manuscript, and, as a consequence, it is much better because of her professional help. My administrative assistant, Maya Stamenkovic, could not have done a better job in creating an atmosphere conducive to my work. Donaldo Macedo, my brother, has always been there for me and even more so as I was writing this book.

As usual, Dean Birkenkamp, my friend and publisher, has provided invaluable support and insight in bringing this book to press. It is an amazing experience to have a publisher who is as brilliant as he is professional. I feel blessed having him in my life, as I know do many of his other authors.

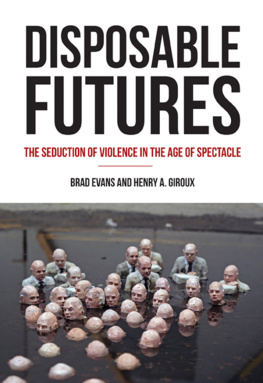

In choosing an image for the cover of this book, I wanted to use a representation that was not news-specific, one whose representational politics captured less the singularity of a particular spectacular event, expression of suffering, or form of abuse than an image that signified a more general, ambiguous representation of both the spectacle of terrorism and the barbarism it evokes. I decided right off not to use an image with a literalness that might be exploitativephotos of the Twin Towers burning, individuals wounded and bleeding, or context-specific acts of barbarism such as someone about to be beheaded. Hence, I did not want to use either historically specific images, such as those that would be unmistakably associated with Abu Ghraib, Iraq, Palestine, Israel, or Chechnya, or those directly related to the events of 9/11. Instead, I chose this non-news-specific image precisely because of its ambiguity. In an age when the appeal to terrorismthe spectacle of terrorism, to be more exactis used by state and nonstate terrorists alike to appropriate fear as a pretext for the most horrendous crimes, I think the image Ive selected reminds us not of the singularity of the particular person behind the hood (is it a woman, a victim of CIA counter-terrorism, a journalist captured by extremist groups in Iraq who is about to be beheaded?) but of the larger political forces that create such horrors through conditions that make such horrendous images and crimes even possible. The cover illustrates an ambivalence about the image that ranges from diplomats who have been kidnapped, Iraqis who have been tortured, dissidents who have been abducted, black men who have been abused in U.S. prisons, students who have been tortured by the police in any one of a number of oppressive regimesand it invites the most awful play of imagination suggesting that the image could be me, you, any of us, and that our lives are not so removed from the play of these forces as to allow us to be either complacent about such acts or, even worse, morally and politically indifferent. And even if the image cannot be imagined privately, it evokes the question of what our responsibility might be to this person behind the hood, not merely/only/exclusively as an ethical question (which is impossible) but also as an educational and political issue. What kind of responsibility do we have to the man, woman, or child who is masked? The image graphically evokes not simply our own vulnerability but also, along with the titles call to move beyond, our complicity. After all, that image is everywhere and it indicts us all. What I like about the ambiguity of the image is that it does not register one specific historical moment such as Abu Ghraib. It is decontextualized in the same way the figure is: This could be anyone, including one of us, and thus says something about both our vulnerability and, more important, our responsibility to address the conditions that create not just the image but the suffering it suggestsa form of suffering that take place within particular forms of material and symbolic relations of power.

Democracy begins to fail and political life becomes impoverished when society can no longer translate private problems into social issues. Unfortunately, that is precisely what is happening in the United States today. In the post-9/11 world, the space of shared responsibility has given way to the space of private fears; the social obligations of citizenship are now reduced to the highly individualized imperatives of consumerism, and militarism has become a central motif of national identity. In this cold new world, the language of politics is increasingly mediated through a spectacle of terrorism in which fear and violence become central modalities through which to grasp the meaning of self in society. While efforts to collapse the public into the private have a long history in American political culture, such attempts have taken on a new forcefulness in the age of terror as nation-states have become both more authoritarian and increasingly vulnerable to assault from unknown sources. Law and violence have become indistinguishable as societies enter into a legitimation crisis, unable to guarantee protection to their citizens while intensifying a culture of fear that appears to mimic the very practices used by nonstate terrorists to spread their ideologies.1 As the war on terrorism takes aim at justice, democracy, and political autonomy, images of hatred, violence, and destruction become enshrined in the special effects made possible by new media technologies such as camcorders, mobile camera-phones, satellite television, digital recorders, and the Internet. Screen culture has emerged as a crucial pedagogical tool, administering a 24hour series of visceral shocks to viewers, radically displacing their former selves as consumers of material goods; now they are organized largely through shared fears rather than shared responsibilities. Under the spectacle of terrorism, the state relies more heavily on its security functions, and nonstate terrorists rewrite the space of the political and social through a circuit of anxiety, panic, destruction, and revenge that makes an ethical response moot and a democratic conception of politics, in the words of Attorney General Alberto Gonzales, quaint. As the culture of fear and the spectacle of terrorism become indistinguishable, everyday life undergoes a structural and political transformation, fusing sophisticated, electronic technologies with a ubiquitous screen culture while simultaneously expanding the range of cultural producers and recipients of information and images.2