Originally published in 1969 by Frederick A, Praeger, Publishers

Published 2004 by Transaction Publishers

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

New material this edition copyright 2004 by Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2004043977

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

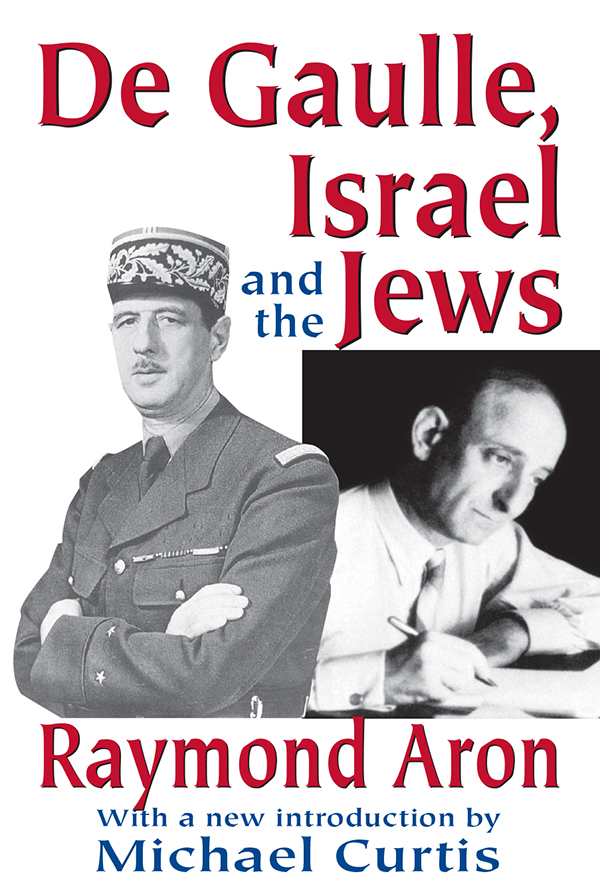

Aron, Raymond, 1905-

[De Gaulle, Israel et les Juifs. English]

De Gaulle, Israel and the Jews / Raymond Aron ; with a new introduction by

Michael Curtis.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p.) and index. ISBN 0-7658-0925-7

(pbk.: alk. paper)

1. Israel-Arab War, 1967Infuence. 2. Israel and the diaspora. 3. Gaulle,

Charles de, 1890-1970. I. Title.

DS127.85.A7813 2004

956.046dc22

2004043977

ISBN 13: 978-0-7658-0925-4 (pbk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this book but points out that some imperfections from the original may be apparent.

Introduction to the Transaction Edition

The lives of Raymond Aron and Charles de Gaulle intersected at significant moments in twentieth-century history, cooperatively in London during World War II, and antagonistically in Paris as a result of the presidents press conference on November 27, 1967. The two Frenchmen formed an incongruous duo. General de Gaulle, the heroic man of June 18, 1940, the symbol of French resistance to Nazi Germany, the founder and president of the French Fifth Republic, was the quintessential exponent of the grandeur and national sovereignty of France. Aron, the brilliant scholar and journalist, the intellectually courageous critic of the prevailing, fashionable, politically correct attitude of sympathy and tolerance among the French intellectual and cultural elite towards the actions of the Soviet Union, was the de-judaized Jew who had rallied to the Free French movement in London in 1940 but was not an unqualified admirer of Charles de Gaulle during or after World War II.

Raymond Aron early showed his brilliance by being placed first in the agrgation in 1928, after four years at the Ecole Normale Suprieure, in a class that included Jean-Paul Sartre, Paul Nizan, and Georges Canguilhem. His experience while studying in Germany, in Cologne and Berlin, from 1930 to 1933, made him acutely aware of the threat and violence of Nazism. In London during the war he was the acting editor, together with Andr Lebarthe as manager, of La France libre, the monthly review of the Free French movement which first appeared there in November 1940 and for which Aron wrote in fifty-seven of the fifty-nine issues.

Aron had taught philosophy at Le Havre before the war, worked at the Centre de Documentation Sociale de lEcole Normale Suprieure, and was to have a distinguished academic career, at the Sorbonne (1955), at the Ecole pratique des Hautes Etudes in 1960, at the Collge de France, as professor of European civilization from 1970 to 1979. During that career, as philosopher, historian, sociologist, and political scientist, he published over forty books. Important as was his scholarship, more influential for the general public were Arons journalism and editorial writing for Combat (April 1946 to June 1947), Le Figaro (1947 to 1977), LExpress (1977 to 1983), and the monthly Preuves, Commentaire, and Encounter. Addressing almost daily both domestic and international issues, Aron in his thousands of articles was the model of polite but frank discourse and reasoned argument and analysis.

Arons writings, both scholarly and journalistic, spanned an extraordinary range of subjects, including international relations, sociology, economics, ethics, liberalism and the crisis of democracy, intellectual history, war and peace, the concepts and implications of industrial society, and current ideologies. Aron concentrated on concrete issues rather than on formal or epistemological problems. Because of his independent, non-partisan judgments and objective analysis, people found it difficult to place him in any particular political category. That objective analysis was grounded in a realistic assessment of political behavior. In his inaugural lecture on December 1, 1970 he explained that his experience in Germany in the early 1930s had marked him and inclined him to an active pessimism: I lost faith and held on, not without effort, to hope. His objective as a historian was, by retrospective analysis of possibilities, to reveal the articulations of the historical process. He was also a committed observer, prepared to take a position on historical and contemporary events. As active citizen, Aron, a man with good connections in French society unattached to any political party, participated in the work of some anti-communist groups in France and was a member in 1950 of the executive committee of the Congress for Cultural Freedom. As an advocate of reasoned discussion he was particularly critical of the violence and psychodrama exhibited by Parisian intellectuals and students in the university riots in 1968.

Arons writings, like his life, were lacking in ostentation. They were clear, precise, sober, and moderate in tone, critical of ideologies he considered false or embodying fanaticism. They had the cool, urbane tone of classical French expression, free from Teutonic obscurity or turgidity. Aron was particularly critical of those literateurs, such as his former classmate Sartre and companion Simone de Beauvoir, whose writings he viewed as justifying deprivation of liberty of other people at the hands of totalitarianism and terror. In his most well known work, The Opium of the Intellectuals, published in 1955, Aron sought to reduce the poetry of ideology to the level of the prose of reading. Why, he asked, are some intellectuals ready to accept the worst crimes as long as they are committed in the name of the supposedly proper doctrines? His criticism was particularly applicable to Sartre, Merleau-Ponty, and their disciples, with their abstract theories of the left and the Revolution, their moralizing, their disregard of contemporary political reality, their hatred of the bourgeoisie, their existentialist theory of pure freedom in a different society, boundless, universal.