Orlando Figes - The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalins Russia

Here you can read online Orlando Figes - The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalins Russia full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2008, publisher: Penguin, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalins Russia

- Author:

- Publisher:Penguin

- Genre:

- Year:2008

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalins Russia: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalins Russia" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalins Russia — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalins Russia" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The Whisperers

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Peasant Russia, Civil War:

The Volga Countryside in Revolution, 19171921

A Peoples Tragedy:

The Russian Revolution, 18911924

Interpreting the Russian Revolution:

The Language and Symbols of 1917

(with Boris Kolonitskii)

Natashas Dance:

A Cultural History of Russia

ORLANDO FIGES

Private Life in Stalins Russia

ALLEN LANE

an imprint of

PENGUIN BOOKS

ALLEN LANE

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland

(a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

www.penguin.com

First published 2007

1

Copyright Orlando Figes, 2007

The moral right of the author has been asserted

All rights reserved

Without limiting the rights under copyright

reserved above, no part of this publication may be

reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system,

or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior

written permission of both the copyright owner and

the above publisher of this book

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

EISBN: 9780141808871

For my mother, Eva Figes (ne Unger, Berlin 1932) and to the memory of the family we lost

Russian names are spelled in this book according to the standard (Library of Congress) system of transliteration, but some Russian spellings are slightly altered. To accommodate common English spellings of well-known Russian names I have changed the Russian ii ending to a y in surnames (for example, Trotskii becomes Trotsky) but not in all first names (for example, Georgii) or place names. To aid pronunciation I have opted for Pyotr instead of Petr, Semyon instead of Semen, Andreyev instead of Andreev, Yevgeniia instead of Evgeniia, and so on. In other cases I have chosen simple and familiar spellings that help the reader to identify with Russian names that feature prominently in the text (for example, Julia instead of Iuliia and Lydia instead of Lidiia). For the sake of clarity I have also dropped the Russian soft sign from all personal and place names (so that Iaroslavl becomes Iaroslavl and Norilsk becomes Norilsk). However, bibliographical references in the notes preserve the Library of Congress transliteration to aid those readers who wish to consult the published sources cited.

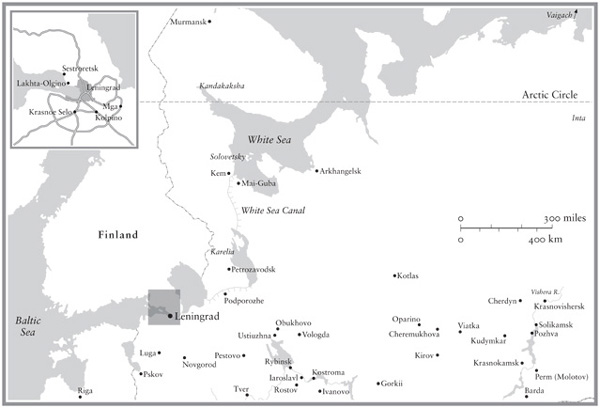

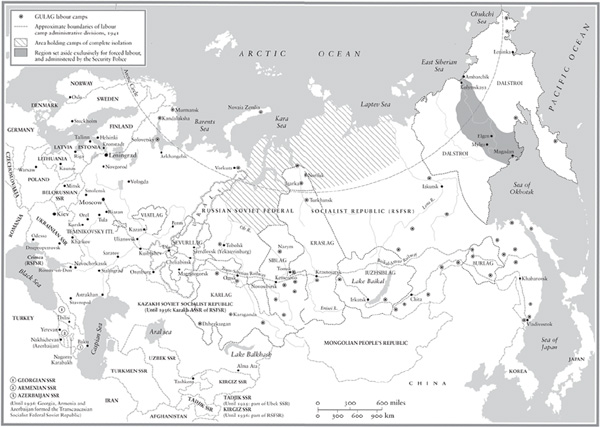

Northern European USSR

Southern European USSR

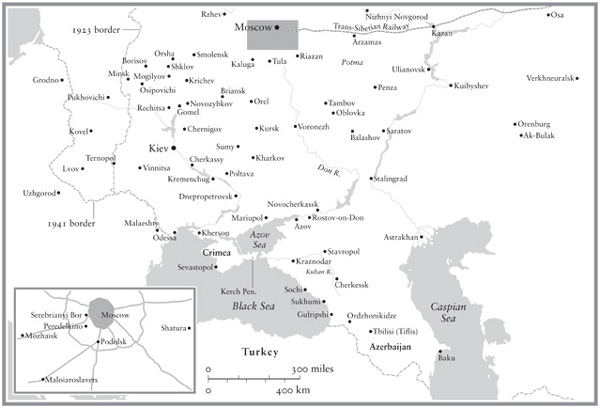

Western and Central Siberia

Eastern Siberia

The Soviet Union in the Stalin era

Antonina Golovina was eight years old when she was exiled with her mother and two younger brothers to the remote Altai region of Siberia. Her father had been arrested and sentenced to three years in a labour camp as a kulak or rich peasant during the collectivization of their northern Russian village, and the family had lost its household property, farming tools and livestock to the collective farm. Antoninas mother was given just an hour to pack a few clothes for the long journey. The house where the Golovins had lived for generations was then destroyed, and the rest of the family dispersed: Antoninas older brothers and sister, her grandparents, uncles, aunts and cousins fled in all directions to avoid arrest, but most were caught by the police and exiled to Siberia, or sent to work in the labour camps of the Gulag, many of them never to be seen again.

Antonina spent three years in a special settlement, a logging camp with five wooden barracks along a river bank where a thousand kulaks and their families were housed. After two of the barracks were destroyed by heavy snow in the first winter, some of the exiles had to live in holes dug in the frozen ground. There were no food deliveries, because the settlement was cut off by the snow, so people had to live from the supplies they had brought from home. So many of them died from hunger, cold and typhus that they could not all be buried; their bodies were left to freeze in piles until the spring, when they were dumped in the river.

Antonina and her family returned from exile in December 1934, and, rejoined by her father, moved into a one-room house in Pestovo, a town full of former kulaks and their families. But the trauma she had suffered left a deep scar on her consciousness, and the deepest wound of all was the stigma of her kulak origins. In a society where social class was

This fear stayed with Antonina all her life. The only way that she could conquer it was to immerse herself in Soviet society. Antonina was an intelligent young woman with a strong sense of individuality. Determined to overcome the stigma of her birth, she studied hard at school so that one day she could gain acceptance as a social equal. Despite discrimination, she did well in her studies and gradually grew in confidence. She even joined the Komsomol, the Communist Youth League, whose leaders turned a blind eye to her kulak origins because they valued her initiative and energy. At the age of eighteen Antonina made a bold decision that set her destiny: she concealed her background from the authorities a high-risk strategy and even forged her papers so that she could go to medical school. She never spoke about her family to any of her friends or colleagues at the Institute of Physiology in Leningrad, where she worked for forty years. She became a member of the Communist Party (and remained one until its abolition in 1991), not because she believed in its ideology, or so she now claims, but because she wanted to divert suspicion from herself and protect her family. Perhaps she also felt that joining the Party would help her career and bring her professional recognition.

Antonina concealed the truth about her past from both her husbands, each of whom she lived with for over twenty years. She and her first husband, Georgii Znamensky, were life-long friends, but they rarely spoke to one another about their families pasts. In 1987, Antonina received a visit from one of Georgiis aunts, who let slip that he was the son of a tsarist naval officer executed by the Bolsheviks. All those years, without knowing it, Antonina had been married to a man who, like her, had spent his youth in labour camps and special settlements.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalins Russia»

Look at similar books to The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalins Russia. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalins Russia and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.