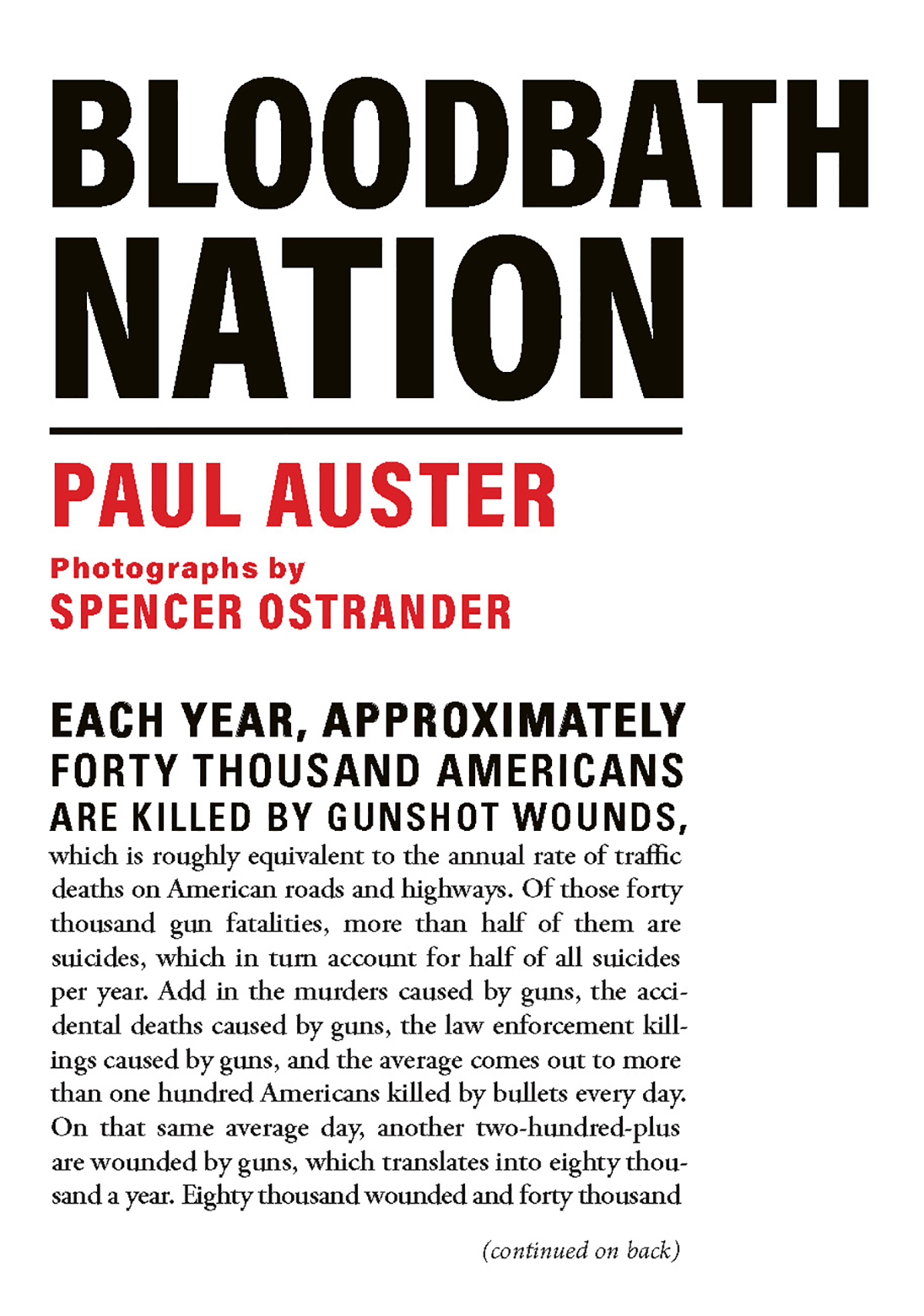

BLOODBATH

NATION

Also by Paul Auster

The Invention of Solitude

The New York Trilogy

In the Country of Last Things

Moon Palace

The Music of Chance

Leviathan

Mr. Vertigo

Smoke & Blue in the Face

Hand to Mouth

Lulu on the Bridge

Timbuktu

The Book of Illusions

The Red Notebook

Oracle Night

The Brooklyn Follies

Travels in the Scriptorium

The Inner Life of Martin Frost

Man in the Dark

Invisible

Sunset Park

Winter Journal

Here and Now (with J. M. Coetzee)

Report from the Interior

A Life in Words (with I. B. Siegumfeldt)

4 3 2 1

Talking to Strangers

White Spaces

Groundwork

Burning Boy

BLOODBATH

NATION

PAUL AUSTER

Photographs by

SPENCER OSTRANDER

Grove Press

New York

Text copyright 2023 by Paul Auster

Photographs copyright 2023 by Spencer Ostrander

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove Atlantic, 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY 10011 or .

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

First Grove Atlantic hardcover editon: January 2023

ISBN 978-0-8021-6045-4

eISBN 978-0-8021-6046-1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available for this title.

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove Atlantic

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

groveatlantic.com

AUTHORS NOTE

The images that accompany the words of this book are photographs of silence. Over the course of two years, Spencer Ostrander made several long-distance trips around the country to take pictures of the sites of more than thirty mass shootings that have occurred in recent years. The pictures are notable for the absence of human figures in them and the fact that no gun or even the suggestion of a gun is anywhere in sight. They are portraits of buildings, often bleak, ugly buildings in undistinctive, neutral American landscapes, forgotten structures where horrendous massacres were carried out by men with rifles and guns, briefly capturing the countrys attention and then fading into oblivion until Ostrander showed up with his camera and transformed them into gravestones of our collective grief.

I have never owned a gun. Not a real gun, in any case, but for two or three years after emerging from diapers, I walked around with a six-shooter dangling from my hip. I was a Texan, even though I lived in the suburbs outside Newark, New Jersey, for back in the early fifties the Wild West was everywhere, and numberless legions of small American boys were proud owners of a cowboy hat and a cheap toy pistol tucked into an imitation leather holster. Occasionally, a roll of percussion caps would be inserted in front of the pistols hammer to imitate the sound of a real bullet going off whenever we aimed, fired, and eliminated one more bad guy from the world. Most of the time, however, it was sufficient merely to pull the trigger and shout, Bang, bang, youre dead!

The source of these fantasies was television, a new phenomenon that began reaching large numbers of people precisely at the time of my birth (1947), and because my father happened to own an appliance store that peddled several brands of TVs, I have the distinction of being one of the first people anywhere in the world to have lived with a television set from the day I was born. Hopalong Cassidy and The Lone Ranger were the two shows I remember best, but the afternoon programming during my preschool years also featured a daily onslaught of B Westerns from the thirties and early forties, in particular those starring handsome, athletic Buster Crabbe and his old geezer sidekick, Al St. John. Everything about those films and shows was pure claptrap, but at three and four and five I was too young to understand that, and a world sharply divided between men in white hats and men in black hats was perfectly suited to the thwarted capacities of my young, primitive mind. My heroes were good-hearted dumbbells, slow to anger, reluctant to talk, and shy around women, but they knew right from wrong, and they could outpunch and outshoot the crooked ones whenever a ranch or a herd of cattle or the safety of the town were threatened.

Everyone carried a gun in those stories, both heroes and villains alike, but only the heros gun was an instrument of righteousness and justice, and because I did not imagine myself to be a villain but a hero, the toy six-shooter strapped to my waist was a sign of my own goodness and virtue, tangible proof of my idealistic, make-believe manhood. Without the gun, I wouldnt have been a hero but a no one, a mere kid.

I longed to own a horse during those years, but not once did it occur to me to wish for a real weapon or even to fire one. When the chance finally came to do that, I was nine or ten and had long outgrown my infantile dreamworld of television cowboys. I was an athlete now, with a particular devotion to baseball, but also a reader of books and a sometime author of wretchedly bad poems, a boy plodding along the zigzag path toward becoming a bigger boy. That summer, my parents sent me to a sleepaway camp in New Hampshire, where in addition to baseball there was swimming, canoeing, tennis, archery, horseback riding, and a couple of sessions a week at the shooting range, where I first experienced the pleasures of learning how to handle a .22-caliber rifle and pumping bullets into a paper target affixed to a wall some twenty-five or fifty yards away (I forget the exact distance, but it seemed just right to me at the timeneither too close nor too far). The counselor who instructed us knew his business well, and I have vivid memories of being taught how to position my hands when holding the rifle, how to line up the target along the sight at the end of the barrel, how to breathe properly when preparing to shoot, and how to pull back the trigger in a slow, smooth motion to send the bullet surging through the barrel into the air. My eyesight was sharp back then, and I caught on quickly, first from a prone position, where I once scored a forty-seven out of a possible fifty from the five shots that made up a round, and then from a sitting position, which entailed a whole new inventory of techniques, but just as I was about to advance to the kneeling position, the summer ended, and so ended my career as a marksman. My parents decided that the camp was too far away and sent me to another one less than half the distance from home the following summer, where riflery was not on the menu of activities. A small disappointment, perhaps, but in all other ways the second camp was superior to the first, and I didnt give the matter much thought. Nevertheless, more than sixty years later, I still remember how good it felt to fire a shot clear into the bullseye, which brought with it a sense of fulfillment similar to the one I experienced whenever I dashed out from my position at shortstop to catch a relay throw from the left fielder and then wheeled around to throw the ball to the catcher as a runner steamed around third base and headed for home. A sense of connection between myself and someone or something a great distance from me, and to throw a ball or fire a bullet and hit the target for the sake of some predetermined goalto prevent a run from crossing the plate, to run up a high score at the shooting rangeproduced a deep, glowing sense of satisfaction and achievement. The connection was what counted, and whether the instrument of that connection was a ball or a bullet, the feeling was the same.