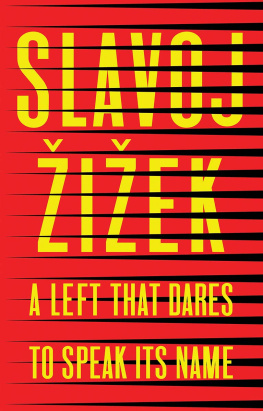

FIRST AS TRAGEDY,

THEN AS FARCE

FIRST AS TRAGEDY,

THEN AS FARCE

SLAVOJ IEK

VERSO

London New York

First published by Verso 2009

Slavoj iek 2009

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-84467-428-2

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Typeset by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed in the US by Maple Vail

Contents

Introduction:

The Lessons of the First Decade

The title of this book is intended as an elementary IQ test for the reader: if the first association it generates is the vulgar anti-communist clichYou are righttoday, after the tragedy of twentieth-century totalitarianism, all the talk about a return to communism can only be farcical!then I sincerely advise you to stop here. Indeed, the book should be forcibly confiscated from you, since it deals with an entirely different tragedy and farce, namely, the two events which mark the beginning and the end of the first decade of the twenty-first century: the attacks of September 11, 2001 and the financial meltdown of 2008.

We should note the similarity of President Bushs language in his addresses to the American people after 9/11 and after the financial collapse: they sounded very much like two versions of the same speech. Both times Bush evoked the threat to the American way of life and the need to take fast and decisive action to cope with the danger. Both times he called for the partial suspension of American values (guarantees of individual freedom, market capitalism) in order to save these very same values. From whence comes this similarity?

Marx began his Eighteenth Brumaire with a correction of Hegels idea that history necessarily repeats itself: Hegel remarks somewhere that all great events and characters of world history occur, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce. This supplement to Hegels notion of historical repetition was a rhetorical figure which had already haunted Marx years earlier: we find it in his A Contribution to the Critique of Hegels Philosophy of Right, where he diagnoses the decay of the German ancien rgime in the 1830s and 1840s as a farcical repetition of the tragic fall of the French ancien rgime:

It is instructive for [the modern nations] to see the ancien rgime, which in their countries has experienced its tragedy, play its comic role as a German phantom. Its history was tragic as long as it was the pre-existing power in the world and freedom a personal whimin a word, as long as it believed, and had to believe, in its own privileges. As long as the ancien rgime, as an established world order, was struggling against a world that was only just emerging, there was a world-historical error on its side but not a personal one. Its downfall was therefore tragic.

The present German regime, on the other handan anachronism, a flagrant contradiction of universally accepted axioms, the futility of the ancien rgime displayed for all the world to seeonly imagines that it still believes in itself and asks the world to share in its fantasy. If it believed in its own nature, would it try to hide that nature under the appearance of an alien nature and seek its salvation in hypocrisy and sophism? The modern ancien rgime is rather merely the clown of a world order whose real heroes are dead. History is thorough and passes through many stages while bearing an ancient form to its grave. The last phase of a world-historical form is its comedy. The Greek gods, who already died once of their wounds in Aeschyluss tragedy Prometheus Bound, were forced to die a second deaththis time a comic onein Lucians Dialogues. Why does history take this course? So that mankind may part happily with its past. We lay claim to this happy historical destiny for the political powers of Germany.

Twelve years prior to 9/11, on November 9, 1989, the Berlin Wall fell. This event seemed to announce the beginning of the happy 90s, Francis Fukuyamas utopia of the end of history, the belief that liberal democracy had, in principle, won out, that the advent of a global liberal community was hovering just around the corner, and that the obstacles to this Hollywood-style ending were merely empirical and contingent (local pockets of resistance whose leaders had not yet grasped that their time was up). September 11, in contrast, symbolized the end of the Clintonite period, and heralded an era in which new walls were seen emerging everywhere: between Israel and the West Bank, around the European Union, along the USMexico border, but also within nation-states themselves.

In an article for Newsweek, Emily Flynn Vencat and Ginanne Brownell report how today,

the members-only phenomenon is exploding into a whole way of life, encompassing everything from private banking conditions to invitation-only health clinics... those with money are increasingly locking their entire lives behind closed doors. Rather than attend media-heavy events, they arrange private concerts, fashion shows and art exhibitions in their own homes. They shop after-hours, and have their neighbors (and potential friends) vetted for class and cash.

A new global class is thus emerging with, say, an Indian passport, a castle in Scotland, a pied--terre in Manhattan and a private Caribbean island the paradox is that the members of this global class dine privately, shop privately, view art privately, everything is private, private, private. They are thus creating a life-world of their own to solve their anguishing hermeneutic problem; as Todd Millay puts it: wealthy families cant just invite people over and expect them to understand what its like to have $300 million. So what are their contacts with the world at large? They come in two forms: business and humanitarianism (protecting the environment, fighting against diseases, supporting the arts, etc.). These global citizens live their lives mostly in pristine naturewhether trekking in Patagonia or swimming in the translucent waters of their private islands. One cannot help but note that one feature basic to the attitude of these gated superrich is fear: fear of external social life itself. The highest priorities of the ultrahigh-net-worth individuals are thus how to minimize security risksdiseases, exposure to threats of violent crime, and so forth.

In contemporary China, the new rich have built secluded communities modeled upon idealized typical Western towns; there is, for example, near Shanghai a real replica of a small English town, including a main street with pubs, an Anglican church, a Sainsbury supermarket, etc.the whole area is isolated from its surroundings by an invisible, but no less real, cupola. There is no longer a hierarchy of social groups within the same nationresidents in this town live in a universe for which, within its ideological imaginary, the lower class surrounding world simply