THE KARMA OF BROWN FOLK

THE KARMA OF BROWN FOLK

vijay prashad

Copyright 2000 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota

The University of Minnesota Press gratefully acknowledges permission to reprint the following. contains an excerpt of poetry from Ghandi Is Fasting, from The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes, by Langston Hughes (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994); copyright 1994 by the Estate of Langston Hughes and reprinted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

Every effort was made to obtain permission to reproduce material used in this book. If any proper acknowledgment has not been made, we encourage copyright holders to notify us.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published by the University of Minnesota Press

111 Third Avenue South, Suite 290

Minneapolis, MN 55401-2520

http://www.upress.umn.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Prashad, Vijay.

The karma of Brown folk / Vijay Prashad.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 0-8166-3438-6 (hc) ISBN 0-8166-3439-4 (pbk.)

1. South Asian AmericansRace identity. 2. South Asian AmericansSocial conditions. 3. East Indian AmericansRace identity. 4. East Indian AmericansSocial conditions. 5. United StatesRace relations. 6. RacismUnited States. I. Title.

E184.S69 P73 2000

305.8914073dc21

99-047918

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

The University of Minnesota is an equal-opportunity educator and employer.

11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 01 00 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

Preface

Karma Sutra: The Forethought

PREFACE

KARMA SUTRA: THE FORETHOUGHT

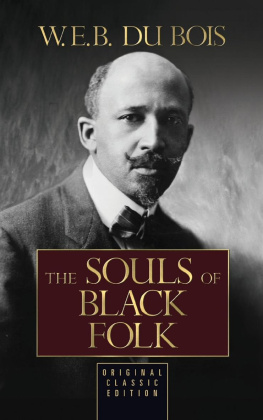

I first stumbled upon W. E. B. Du Boiss The Souls of Black Folk (1903) some two decades ago in a cluttered bookstore on Free School Street in Calcutta. Why I selected that book instead of the many tattered novels that I normally purchased, I cannot say. My only recollection is that after I read the book, even so far away, it moved me deeply. Part of the magic was the style, the sheer exuberance of the prose, but the main reason was the way Du Bois so lovingly offered his sharp criticism of the effects of white supremacy. Reading the book over and over again, I cherish the throaty cadences of Ma Rainey mixed in with the stern dialectics of Hegel, the popular traditions that Du Bois sought after and the elite theories that provided him with a framework. The book you hold in your hand is offered as my flawed attempt to draw from Du Bois as I write of my South Asian American brethren whose presence in the United States complicates the narrative Du Bois offered a century ago. How does it feel to be a problem? Du Bois begins Souls. As South Asians have entered the United States in the past thirty years, there has been a tendency to compare our destiny with that of black folk. If these brown folk can make it, say people like Thomas Sowell, Dinesh DSouza, and the neoconservatives, then why cant black folk? A hundred years after Souls, Du Boiss question remains.

But there is also another question that needs to be asked, and this book will take it as its central problem: How does it feel to be a solution? Addressed to all Asians, but increasingly with special reference to South Asians, this question asks us brown folk how we can live with ourselves as we are pledged and sometimes, in an act of bad faith, pledge ourselves, as a weapon against black folk. What does it mean, this book asks, for us to mollify the wrath of white supremacy by making a claim to a great destiny when we are ourselves only a product of state engineering through immigration controls and of the beneficence of more socialized systems of education in South Asia, or when we are but the children of those who have accumulated a certain amount of cultural capital because of those processes? This book, then, is about the feelings, the consciousness of being South Asian, of being desi (those people who claim ancestry of South Asia) in the United States. It is also a set of sutras (aphorisms) of the karma (fate) of desis, who must now imagine ourselves within the U.S. racial formation and seek to mediate between the dream of America and our own realities.

In 1938, while fascism crept into place in Europe, while imperialism continued to do its dirty deeds in India, and while Jim Crow preened over black folks in the United States, Du Bois bemoaned Indias temptation to stand apart from the darker peoples and seek her affinities among whites. She has long wished to regard herself as Aryan, rather than colored and to think of herself as much nearer physically and spiritually to Germany and England than to Africa, China or the South Seas. And yet, the history of the modern world shows the futility of this thought. European exploitation desires the black slave, the Chinese coolies Du Bois opened his heart to a wide solidarity, an invitation that desis and others need to accept even at this late date. Since we, as desis, are used as a weapon in the war against black America, we must in good faith refuse this role and find other places for ourselves in the moral struggles that grip the United States.

This book emerges from participation in that moral struggle, especially in the time I have spent with my fellow desis in our various political activities. Many of the ideas that follow developed in discussions with activists and students across the country, and some saw the first light of day in our community periodicals. In June 1998 I sat with my computer and my many notes to lay bare some of these ideas and to offer a view on the trials of desis in the United States. There are several good historical overviews on the same topic, and there are also many fine essays that sketch out some of the points that I will simply indicate in the text that follows. Though this book does offer a historical look at U.S. desi life, it attempts to address the dilemmas of desi life in the United States and it suggests passages to transform our current aporias.

There is much in this book that may appear parochial, but if we are to be truly critical multiculturalists, we must be willing to enter domains without safe translations so that we can understand and engage with the complexities that affect the lives of others. There is, in other words, something refreshingly educational about parochiality. Given other circumstances, I would have much rather addressed this book to an unmarked human subject, one who is like the Subject of so much European philosophy, but such a choice is not available as long as race continues to be a searing category through which we are so habitually forced to live.since we might want to allow those who fight from standpoints of oppression to come from concrete identities (such as race, but also ethnicity, regions, sexuality, gender, and class) to produce forms of unity that can only be seen in struggle rather than in some abstract theoretical arithmetic. Most notions of identity are not unalloyed, and many celebrate the importance of the politics of identification; we must learn to harness these identifications in the hope of a future rather than denying the right of oppressed peoples to explore their own cultural resources toward the construction of a complex political will.

The ethos of identification requires that we be scrupulous about the different histories of differentiated groups, that we not assume that all people come at identification from the same place. Such an exercise allows us to see the specific cultural locations of groups and provide some avenues toward the creation of a moral solidarity for our present struggles.

Next page