All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Produced in the United States of America.

INTRODUCTION

AFTER THE ATTACKS OF 9/11, THE UNITED STATES WENT TO war against Al Qaeda and the Taliban in Afghanistan and, in 2003, against Iraq. Many American lives were lost and military personnel maimed. To sustain these military operations, the government borrowed billions of dollars. These obligations, together with the Bush tax cuts, the 2008 economic meltdown, and the Obama administration's stimulus program, have created a national debt that now exceeds $17 trillion, an amount greater than our Gross Domestic Product. Many Americans are left wondering: Can such a huge debt ever be paid offand, if so, how? And, if not, then what?

Anguish over the national debt, exacerbated by bitter political partisanship, underpins our current drift from one crisis to another. In the summer of 2011, the House of Representatives flirted with defaulting on our debt obligations, and the nation's credit rating was downgraded for the first time ever. On January 1, 2013, Congress allowed the country to dip briefly over the so-called fiscal cliff. The so-called sequester, imposing huge across-the-board cuts in federal expenditures, took effect on March 1, 2013, but did not stop debtgrowth. In October, Congress again toyed with default on the debt and shut the government down for sixteen days. Despite enactment of a bipartisan budget deal in January 2014, the future remains unclear. One thing, however, is certain: How to address the debt issue will remain a matter of contention.

Yet anguish over our national indebtedness is not a twenty-first century novelty. It characterized our politics for two decades following 1815. The same concerns arose then as today. How could the debt inherited from the War for Independence, the Louisiana Purchase, and the War of 1812peaking at more than $127 million in 1816 (a tremendous sum in that era)ever be paid off? Yet it was, and its extinction marks the only period in our entire history (two years and ten months, from January 1835 to October 1837) when the United States was debt free. Most Americans are unaware of this episode. It has been largely erased from our national memory.

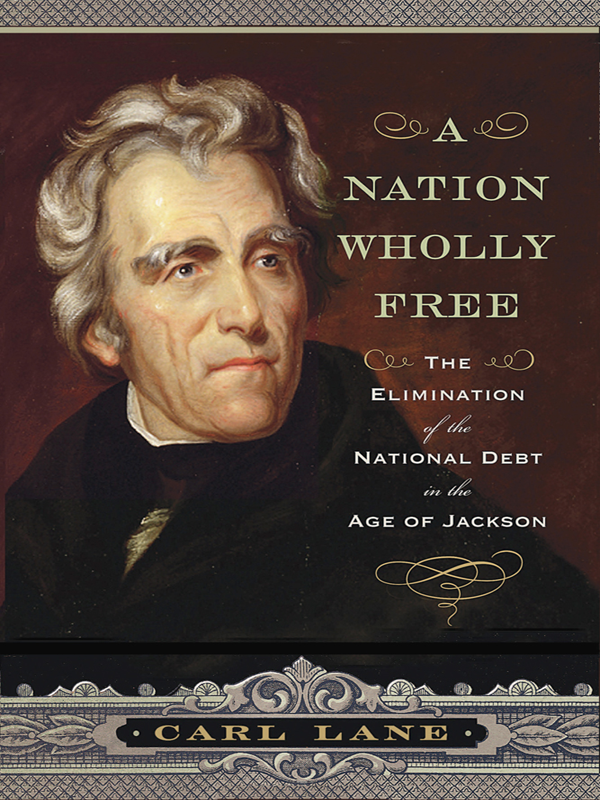

One purpose of this book is to rekindle that memory by telling the story of how debt freedom was secured. It takes its title from the memoir of Missouri senator Thomas Hart Benton, who remarked that after the War of 1812 the question was whether the United States could pay down its national debt and become a nation wholly free. Indeed, eliminating the national debt became a post-1815 priority. The book argues that after President James Monroe announced in late 1824 that the public debt would be extinguished on January 1, 1835, securing debt freedom underpinned much of the politics and policies pursued at the national level. The circumstances surrounding John Quincy Adams's election to the presidency by the House of Representatives in 1825, together with his programmatic agenda, raised doubts about his commitment to debt freedom and doomed his administration to failure. Andrew Jackson, on the other hand, elected president in 1828, was dedicated to national debt freedom, and his determination to achieve it factored into all the major policy decisions of his two administrations. Viewing Jacksonianism from the perspective of debt freedom unifies issues as diverse as internal improvements, the Bank War, the Nullification Crisis of 1832-33, and others that dominated the era. The pursuit of national debt freedom was, infact, a core element of what is often called Jacksonian Democracy. This story is, accordingly, traditional political and policy history, not economic or financial history. It tells a familiar story, but from a new vantage point.

This thesis is not intended to challenge any of the rival schools of thought concerning the Age of Jackson. Rather, it aims to call attention to a common factor in Jacksonian public policy that has been largely overlooked. Remarkably little has been written about the elimination of the national debt in 1835. In addition, this book aims at encouraging further research into the relationship between debt freedom and Jacksonian Democracy. Throughout the text the terms national debt and public debt are used interchangeably.

Moreover, since today we confront a national debt of extraordinary magnitude, I hope that this story will shed light on our current situation. For this reason the book is intended for a general as well as an academic audience. The securing of our debt freedom in 1835 is an interesting story, and I hope that I have told it well. Furthermore, especially in view of our current debt crisis, I also hope that this study will, at the very least, inspire confidence that we can solve our fiscal problems and ensure a prosperous future for our children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. We have lived with public debt for more than 235 years, and obviously we have survived. This study may even offer some guidance on how to address our present debt problem. For these reasons, the book concludes with a brief epilogue comparing and contrasting the situation in Jackson's day with our own.

ONE

CRISIS AND PROMISE: DECEMBER 1824MARCH 1825

ALTHOUGH UNSEASONABLY MILD TEMPERATURES BLESSED THE mid-Atlantic region of the United States in the autumn of 1824, a discomforting political chill greeted members of the eighteenth Congress as they gathered in Washington in early December. Uncertainty and anxiety gripped the air, and for good reason: The recent presidential election had failed to produce a winner. Four candidates had divided the electoral vote in a way that denied a majority to any one of them. Consequently, according to Amendment XII of the Constitution, selection of the next chief executive devolved upon the House of Representatives, each state delegation casting one vote and choosing from the three candidates with the most electoral votes. Yet even the slate of three remained undefined, because the election result in Louisiana, with five electoral votes, was not yet known.

The situation was this: General Andrew Jackson of Tennessee, the popular hero of the War of 1812 and currently a member of the Senate, qualified for the run-off election in the House. He had won only a plurality of electoral votes, the reason why the election was going to the representatives in the first place. Louisiana's five votes were too few to give him a majority. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, second behind Jackson, also qualified, but, even with Louisiana's votes, he could not overcome Jackson's lead. The third candidate for House consideration, however, was either the secretary of the treasury, William H. Crawford of Georgia, or the Speaker of the House, Henry Clay of Kentucky. Clay, who was currently fourth in the electoral tally, needed all five of Louisiana's votes to overtake Crawford and eliminate him from the contest.