The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you without Digital Rights Management software (DRM) applied so that you can enjoy reading it on your personal devices. This e-book is for your personal use only. You may not print or post this e-book, or make this e-book publicly available in any way. You may not copy, reproduce, or upload this e-book, other than to read it on one of your personal devices.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Naima Ahmed and Malcolm Ahmed

C ONTENTS

Temur sat cross-legged on warm stone. Brother Hsiung had brought him tea. Contents untasted, the cup cooled in his hands. The sound of a mountain stream rattling over rocks rose from the bottom of a gully several li below and to his left, but he had lost his immediate awareness of it.

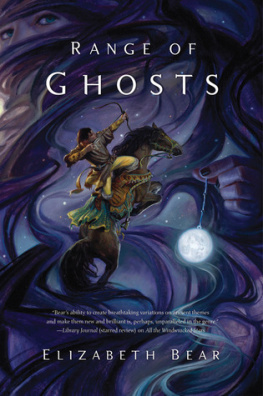

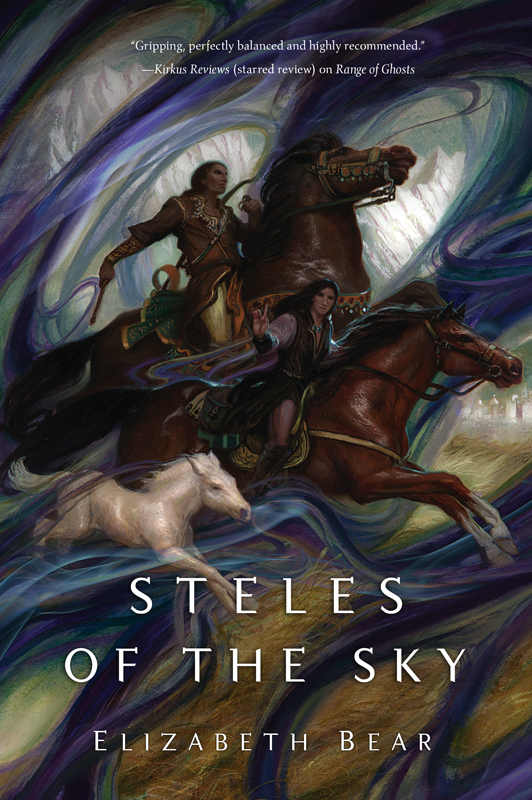

He was watching his mare chase her colt around the twilit meadow while the chill of evening settled on his shoulders. Bansh was of the steppe breed, and her liver-bay coat gathered the dim light and gleamed like shadowed metal but the colt, Afrit, was the unlucky color called ghost-sorrel, and he shone through the gloaming like a pale cream moon.

Beyond them, the shaman-rememberers mouse-colored mare watched, dark eyes in a face white from ears to lip giving her an uncanny resemblance to a horse whose head was a skull. She stood quietly, a mature and stolid creature with her ears pricked tip to tip, seeming amused by the romping of more excitable beasts.

Beyond her, strange jungles that had long overgrown the city called Reason were awakening for the night. Feathery ferns unscrolled from their stony daytime casements. Toothed birds whose legs were feathered jewel-blue and violet like a second set of wings crept from crevices and shook the plumage on their long bony whip-tails into bright fans.

Afrit bucked and snorted, shaking the bristle of his mane. His legsseeming already near as long as his mothersflashed even paler than his cream-colored body, as if he wore white silk stockings gartered above each knee. Bansh stalked him, stiff-legged, head swaying like a snakes. The colt hopped back nimbly for one less than a day old, whirled, boltedand tumbled to the ground in a tangle of twig-limbs.

He scrambled up again and stood, rocky on splayed legs, until Bansh ambled over and nosed him carefully from one end to the other. By the time she reached his tail, hed remembered about the teat, and was busily nursing.

Temur sipped his cold tea. Afrit would have his mothers high-arched nose and good deep nostrils, the fine curve of her neckeven more dramatic with a stallions muscle on it. Hed have her neat, hard feet. The open questions were whether hed ever be able to run on air the way his ever-so-slightly supernatural mother did and what his unlucky, impossible color might presage.

Temur did not look up at the footstep behind him. He knew it: the hard boots and swish of trousers of the Wizard Samarkar. He played a game with himself, imagining her face without looking at her, and breathed deeply to catch the scent of her hair as she settled beside him. He was disappointed: it smelled of dust, and the desert, more than Samarkar.

But her shoulder was warm against his. She leaned into him, reached over. Plucked the cold bowl of tea from his hands and replaced it with one that breathed lazy coils of steam. He lowered his face to the warmth and inhaled. Moisture coated his dry nose and throat.

In pleasure, he sighed.

She drank down the cold tea and set the bowl aside as he turned to her. As always, her real face was far more complex than the one he held in his memory. He never quite remembered the small scar through an eyebrow or the slight irregularity of her nose.

It made him wonder how well he remembered Edene, who he had not seen since the spring.

The stars were shimmering into existence in the deepening sky, constellations hed known all his life and yet had recently wondered if hed ever see again. The Stallion, the Mare. The Oxen and the Yoke that bound them. The Ghost Dog. The Eagle.

It was strange seeing them framed in mountains on all sides.

Are you hungry? Samarkar asked at last. Hsiung is making something. Hrahima is off. Somewhere. And the shaman-rememberer is sleeping.

Im waiting for the moons, Temur said. Shed know why; one moon would rise for every son or grandson of the Great Khagan still living.

Temur was checking on his family.

A faint glow limned the ragged outline of the mountains to the east. When Temur glanced west, the stark light made the forested lower slopes there look like the rough undulations of the scholar-stones they carved in Song. Glaciers and smears of early snow glistened at their peaks, broken by the black knife-lines of ridges. His heart squeezed hard and fast, as if a woman caught his eye and smiled.

He looked away as long as he could, though Samarkar reached down and threaded her fingers between his. When he drank the last tea from the bowl he still held in his right hand, it was barely warm.

He set it on the rock beside him and turned to the rising moons.

Once there had been hundreds, a gorgeous procession scattered across the night, light enough to read by. Now a scant double handful drifted one by one into sight. There the Violet Moon, smeared with color like chalk, of Nilufers son Chatagai. There Temurs own Iron Moon, red and charcoal and yet streaked bright. He waited for the pale circle of Qori Buqas Ghost Moon, just the color of Afrits creamy hide

It did not rise.

Only Samarkars breathing told him she was in pain. He had clenched his hand through hers, and must be squeezing the blood from her fingers. When he forced his to open, his own knuckles ached. He stroked her palm in apology; briefly she encircled his wrist.

Who? she asked.

He shook his head, but said, Qori Buqa is dead. If the sky can be trusted

What can be trusted, if the sky cannot?

He tipped his head in acquiescence. Who killed him?

Another rival? But she did not sound confident. Some Song general? Does it change anything? Well still have to fight someone .

He was silent a long time before he answered, Its the way the mill of the world grinds.

She too left the quiet fallow between them for a while before she asked, Have you dreamed this?

His dreamsshamanistic, not quite propheticdated from before the blood-vow that was the reason she had originally chosen to follow him. It had been her wizards scientific bent that had brought her along, in order to study the progress of his oaththat, and a loyalty to her sister-in-law Payma, whom they had smuggled out of the Black Palace one step ahead of the guards.

He shrugged. Not exactly. I dreamed Qori Buqa backward upon a red mare. That could be death. Or it could mean that he goes blind to war.

Went blind, Samarkar corrected. Hes not going anywhere now.

Except on vulture wings, Temur replied.

When Temur looked up again, a moon hed never before seen, a moon banded with rippled dark and bright like the temper-water of a blade, rode among its cousins in the old familiar sky.