Cultures of Knowledge in the Early Modern World

Edited by Ann Blair, Anthony Grafton, and Jacob Soll

The series Cultures of Knowledge in the Early Modern World examines the intersection of encyclopedic, nature, historical, and literary knowledge in the early modern world, incorporating both theory (philosophies of knowledge and authority) and practice (collection, observation, information handling, travel, experiment, and their social and political contexts). Interdisciplinary in nature, the goal of the series is to promote works that illustrate international and inter-religious intellectual exchange and the intersections of different fields and traditions of knowledge.

History, Medicine, and the Traditions of Renaissance Learning

Nancy G. Siraisi

The Information Master: Jean-Baptiste Colberts Secret State Intelligence System

Jacob Soll

Printing and Prophecy: Prognostication and Media Change 14501550

Jonathan Green

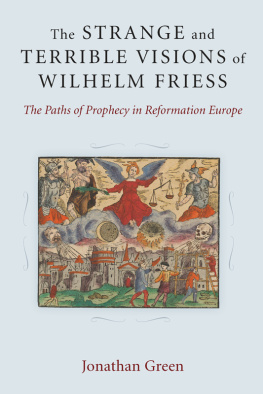

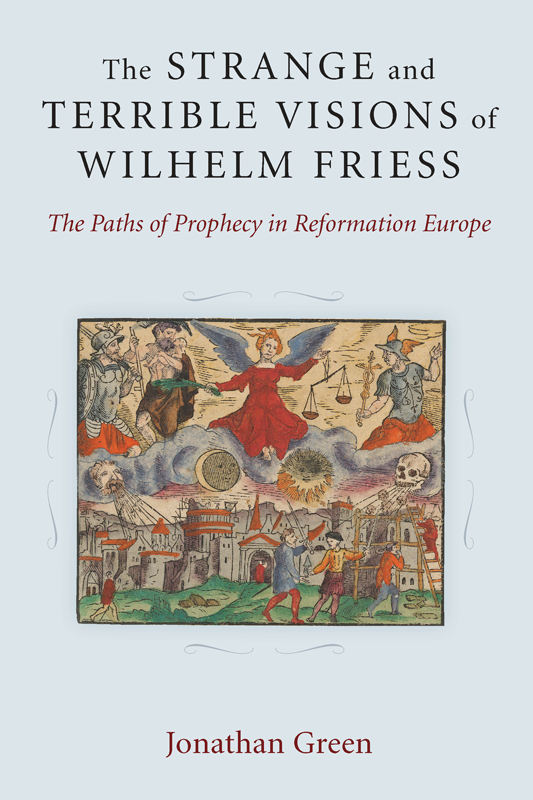

The Strange and Terrible Visions of Wilhelm Friess

Jonathan Green

Copyright Jonathan Green 2014

All rights reserved

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher.

Published in the United States of America by

The University of Michigan Press

Manufactured in the United States of America

Printed on acid-free paper

Printed on acid-free paper

2017 2016 2015 2014 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Green, Jonathan, 1970

The strange and terrible visions of Wilhelm Friess : the paths of prophecy in Reformation Europe / Jonathan Green.

pages cm. (Cultures of knowledge in the early modern world)

Includes Dutch and German versions of Willem de Vrieses prophecies from the years 1558 and 1577 respectively, adaptation of a French version of the Vademecum of Johannes de Rupescissa.

Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-472-11921-9 (hardcover : alk. paper)ISBN 978-0-472-12007-9 (e-book) 1. ProphecyChristianityHistory. 2. Vriese, Willem de Appreciation. 3. Predictive astrologyEurope, German-speaking History. 4. BooksEurope, German-speakingHistory14501600. 5. Apocalyptic literatureHistory and criticism. I. Vriese, Willem de. II. Title.

BR115.P8G745 2014

261.51309409031dc23

2013048766

Preface

As anyone who has gone through the process can attest, the latter stages of publishing a book involve periodic bursts of intense effort under tight deadlines, interspersed with lengthy periods of waiting on all the things that are not under the authors control. During one of those waiting periods while Printing and Prophecy was making its way toward publication, it occurred to me that I would soon have to work on something else. Looking for the next project has always been a process of false starts as one idea proves unworkable and another turns out to have been sitting on the library shelves for the last decade or more, so I thought I would start small. I had limited the scope of Printing and Prophecy to the century following the invention of print, roughly 14501550, so I decided to find out which of the most popular prophetic pamphlets of the later sixteenth century had the least scholarly literature devoted to them. As it turns out, no secondary literature addressed any of them in any depth, including what turned out to be the most popular of them: the prophecies of Wilhelm Friess of Maastricht. I had touched on Wilhelm Friess in Printing and Prophecy, but not at any length, as all its editions were published after 1550. I resolved to write a quick, short article while I tried to figure out what my next major project would be.

As you already know, as you are reading a book rather than a short article, none of that worked out as planned. In the middle of leaving one town and academic position for another, I realized that the Wilhelm Friess pamphlets represented not one text but two (as Robin Barnes had noticed long ago), with no obvious relationship between them. I began tracking down editions and gathering facsimiles. There were many of them.

Within a few months, I had written the article I had planned. I even worked up a cover page and formatted the article for submission, but I could not escape the nagging feeling that I had not yet entirely solved the riddle of Wilhelm Friess and his strange and terrible prophecies. I redoubled my search for new sources, and my tidy little German project soon turned into a Dutch-German-Swiss project that was straining the word-count limits of a journal article. I decided to start writing again to discover if there might just be enough material for a short book, something like the scholarly equivalent of a novella. Ellen Bauerle, the editor who had acquired Printing and Prophecy for the University of Michigan Press (and to whom I am grateful for her early support and continual encouragement), was willing to look at a draft that I thought was nearly complete, and she responded positively.

As you already know, as you are not reading an academic novella, I was actually much farther from completing my research on Wilhelm Friess than I thought at the time. I still could not escape the nagging feeling that I had overlooked something, so I went back to prophecies printed in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries to see if I had overlooked potential sources. Eventually I found them, but not in the century I had expected, so my manageable Dutch-German-Swiss research project added French and Latin sources and another century to its scope.

While Printing and Prophecy mostly examined prophecy from the remote, birds-eye view that media studies often require, working on the prophecies of Wilhelm Friess has entailed a tightly focused examination of a few texts associated with one authorial name, so that the placement of one letter or alteration of one word can become a highly significant detail. The required approach falls toward the mustier side of traditional research methods in the humanities. Yet the methods of textual history and bibliographic inquiry were able to uncover a story that I found to be utterly fascinating and sometimes marked by drama, tragedy, duplicity, and stubborn resistance in the face of overwhelming force. The reader may take comfort in knowing that I am no longer troubled by the feeling that I have overlooked something important: while I have no doubt that I have not discovered every significant connection or relevant contextual fact, the nagging sensation that there is yet more to say is now the responsibility of those who will read this book, uncover and improve on its flaws, and extendor rejectits conclusions.

As this project required me to engage with what were new areas of research for me, I was only able to complete it with the generous assistance of many people and institutions. My thanks go first to the libraries that made their material available for inspection or provided facsimiles, including the Museum Plantin-Moretus in Antwerp, the Erfgoedbibliotheek Hendrik Conscience in Antwerp, the Staatsbibliothek Preuscher Kulturbesitz in Berlin, the Lehrerbibliothek des Grres-Gymnasiums in Dsseldorf, the Eichsttt Universittsbibliothek, the Forschungsbibliothek in Gotha, the Universitts-und Landesbibliothek Halle, the Universiteitsbibliotheek Leiden, the Leipzig Universittsbibliothek, the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in Munich, the Wrttembergische Landesbibliothek in Stuttgart, the Universiteetsbibliotheek Utrecht, the Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek in Weimar, and the Herzog August Bibliothek in Wolfenbttel. In addition to the gratitude I owe their institutions, several librarians and archivists deserve special mention for their personal assistance in locating editions and obtaining facsimiles, including Dr. Karl-Ferdinand Besselmann of the Universitts-und Stadtbibliothek in Cologne, Frank Aurich of the Schsische Landesbibliothek/Staats-und Universittsbibliothek Dresden, Uwe Kahl of the Christian-Weise-Bibliothek Zittau, and Prof. Dr. Christoph Eggenberger and Dr.phil. Alexa Renggli of the Zentralbibliothek Zrich. Several other individuals deserve special thanks for answering inquiries from the other side of the world on obscure topics, including Prof. Dr. Ulrich Seelbach of the Universitt Bielefeld, Prof. Dr. Willem Frijhoff of the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam, Dr. Annelies van Gijsen of the Ruusbroecgenootschap in Antwerp, Dr. L. Wiggers of the Regionaal Historisch Centrum Limburg, and Dr. Wilhelm Klare of the Landeshauptarchiv Sachsen-Anhalt. I especially thank Dr. Oliver Duntze of the Gesamtkatalog der Wiegendrucke for his repeated willingness to answer inquiries and for pulling needles from haystacks on a number of occasions. I owe the interlibrary loan librarians of Brigham Young University my thanks as well for their assistance in locating microfilm facsimiles that would have normally been unobtainable, in which they were rivaled only by the personal efforts of my friend Bill Atkinson. I am grateful for the support that Brigham Young University-Idaho provided for my research and for its providing a place to conduct that research among friendly and supportive colleagues. I also thank all those who read early drafts of this work, including Dr. David Neville, Dr. Francien Markx, Dr. Wilfried Decoo, and the students in my German literature course in fall 2011. Finally, I am grateful most of all for my childrens enduring patience and for the unwavering support and editorial acumen of my wife, Rose, to whom this book is dedicated.

Printed on acid-free paper

Printed on acid-free paper