A Note on Sources

In this work we have, apart from the two last chapters, based ourselves exclusively upon the Sutta-piaka, which contains the most important and most ancient portion of Pli Buddhism.

Many of the Buddhist teachings are set forth in the form of leitmotif, that is to say, of passages that recur in various texts, almost in identical form. Wherever possible we have referred to these motifs in their contexts in the Majjhima-nikya. There was moreover a specific reason for this, namely, that there is accessible to the Italian public a really first-class translation of this text, and which is also a noteworthy work of art, made by K. E. Neumann and G. de Lorenzo (Idiscorsi di Buddha [Bari, 191627] 3 vols.). We have done our best to make the maximum use of this translation. For the other texts we give the reader the following references should he or she wish to refer to them.

Dgha-nikya in Sacred Books of the Buddhists, trans. T. W. Rhys Davids (London, 18991910). For the sutta no. 16, which is the Mahparinibbna-sutta, we have also made use of the Chinese version, translated into Italian by C. Puini (Lanciano, 1919).

Sayutta-nikya, trans. C. A. F. Rhys Davids and F. L. Woodward. Pli text edition (London, 192224), 4 vols.

Anguttara-nikya, ed. Nynatiloka (Die Reden des Buddhas) [Munich and Neubiberg, 192223].

Of the Dhammapada there exists the Italian translation by P. E. Pavolini, Lanciano, ed. Cultura dell'anima.

The quotations from these, as from other texts, follow the paragraphing of the originals. Concerning those that have been made available by H. C. Warren, Buddhism in Translations (Cambridge, Mass., 1909, first published 1896), we have given in brackets the letter W.

For the Vinaya-piaka, see Sacred Books of the East, vol. 13, Dhamma-sangani,trans. C. A. F. Rhys Davids (London, 1900).

Translator's Foreword

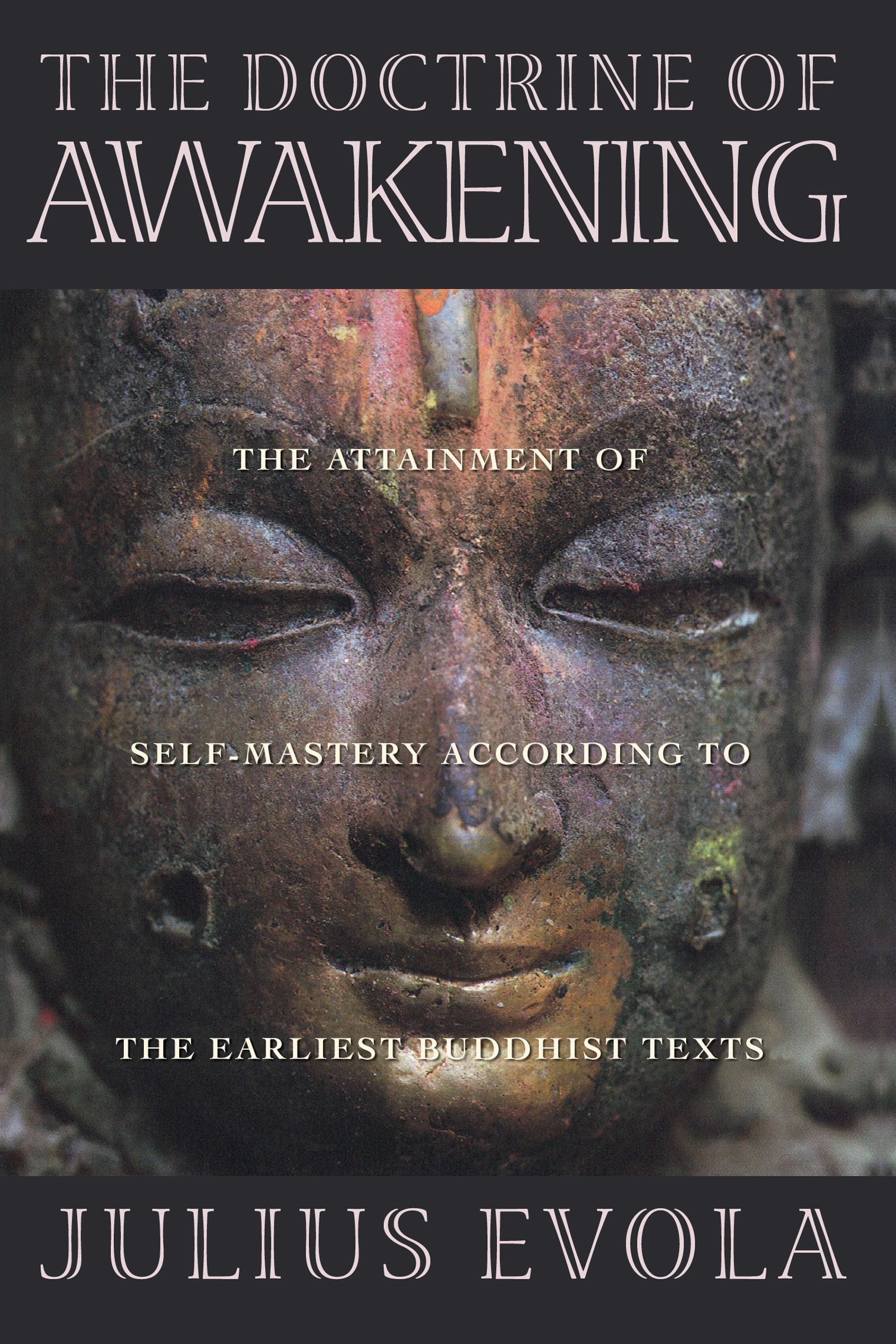

Of the many books published in Italy and Germany by Julius Evola, this is the first to be translated into English. The book needs no apology; the subjectBuddhismis sufficient guarantee of that. But the author has, it seems to me, recaptured the spirit of Buddhism in its original form, and his schematic and uncompromising approach will have rendered an inestimable service even if it does no more than clear away some of the woolly ideas that have gathered round the central figure, Prince Siddhattha, and round the doctrine that he disclosed.

The real significance of the book, however, lies not in its value as a weapon in a dusty battle between scholars, but in its encouragement of a practical application of the doctrine it discusses. The author has not only examined the principles on which Buddhism was originally based, but he has also described in some detail the actual process of "ascesis" or self-training that was practiced by the early Buddhists. This study, moreover, does not stop here; it maintains throughout that the doctrine of the Buddha is capable of application even today by any Western person who really has the vocation. But the undertaking was never easy, and the number who, in this modern world, will succeed in pursuing it to its conclusion is not likely to be large.

H. E. M.

[1948]

Preface

In his autobiography Ilcammino del cinabro (The Cinnabar Path), Julius Evola recalled:

"During the last years of the 1930s I devoted myself to working on two of my most important books on Eastern wisdom: I completely revised L'uomo come potenza [Man As Power], which was given a new title, Lo yoga della potenza [The Yoga of Power], and wrote a systematic work concerning primitive Buddhism entitled La dottrina del risveglio [The Doctrine of Awakening]."

The recent discovery of the correspondence between Evola and his publisher allows us to specify the sequence of events and modify it, at least in part. In a letter dated October 20, 1942, Evola wrote to Laterza with a proposal:

"It is a new book entitled La dottrina del risveglio, carrying the subtitle Saggio sull'ascesi buddista [Essay on Buddhist Asceticism]. This is a work that I have almost completed concerning the practical and virile aspect of Buddhist teachings, with particular emphasis on the striving after the Unconditioned. I believe that my book's exposition of Buddhist teachings on this basis, explained in a way that everybody will understand, constitutes something original and will be of interest to more than a handful of specialized scholars.

After Laterza accepted this project, the final manuscript was mailed on November 30, 1942. It was sent to press in February 1943, and the last revisions were made during the first ten days of August. The book was finally printed in September 1943 during a period of radical political and military upheaval. The author was able to see a copy of La dottrina only after the war was over.

About his book, Evola wrote, "I have paid a debt that I had toward Buddha's doctrine," which had "a definite influence in helping me overcome the inner crisis I experienced right after World War I." He also added:

Later on, I made a practical and rewarding use of Buddhist texts, in order to strengthen a detached awareness of the principle of "being." He who was a prince of the kya pointed out a series of inner disciplines that I felt were very congenial to my spirit, just as I felt religious, and especially Christian, asceticism totally alien to me.

Evola was neither a Buddhist nor a Buddhist scholar, and always considered it a misunderstanding that some would classify him as such. Buddhism was a "way," one among other "ways" available to people who live in the last age, the Kali Yuga. In his autobiography Evola explained his need to explore and to point out to others the various spiritual paths that could be found in Eastern and Western traditions; these paths, he believed, helped one to remain steady in this "age of dissolution." After expounding the "wet path," the path "of affirmation, of the assumption, use, and transformation of immanent forces that are freed until akti's awakening, which is the power root of every vital energy and especially of sex" in the Yoga of Power, in The Doctrine of Awakening he indicated a "dry path," an intellectual approach of pure detachment. Some people have thought of these paths as opposites, but Evola explicitly declared them to be "equivalent, as far as the final goal is concerned, provided they are followed to the end, though one may be preferred to the other depending on the circumstances, one's own nature, and inner, existential dispositions." These words need to be emphasized. They were written in 1963 and express the same point of view as twenty years earlier. Evola noted then that his book was

Next page