Walrus

Animal

Series editor: Jonathan Burt

Already published

Albatross Graham Barwell Ant Charlotte Sleigh Ape John Sorenson Bear Robert E. Bieder

Bee Claire Preston Camel Robert Irwin Cat Katharine M. Rogers Chicken Annie Potts

Cockroach Marion Copeland Cow Hannah Velten Crocodile Dan Wylie

Crow Boria Sax Deer John Fletcher Dog Susan McHugh Dolphin Alan Rauch

Donkey Jill Bough Duck Victoria de Rijke Eel Richard Schweid Elephant Dan Wylie

Falcon Helen Macdonald Fly Steven Connor Fox Martin Wallen Frog Charlotte Sleigh

Giraffe Edgar Williams Gorilla Ted Gott and Kathryn Weir Hare Simon Carnell

Hedgehog Hugh Warwick Horse Elaine Walker Hyena Mikita Brottman

Kangaroo John Simons Leech RobertG. W. Kirk and Neil Pemberton

Leopard Desmond Morris Lion Deirdre Jackson Lobster Richard J. King

Monkey Desmond Morris Moose Kevin Jackson Mosquito Richard Jones

Octopus Richard Schweid Ostrich Edgar Williams Otter Daniel Allen Owl Desmond Morris

Oyster Rebecca Stott Parrot Paul Carter Peacock Christine E. Jackson Penguin Stephen Martin

Pig Brett Mizelle Pigeon Barbara Allen Rabbit Victoria Dickenson Rat Jonathan Burt

Rhinoceros Kelly Enright Salmon Peter Coates Shark Dean Crawford Snail Peter Williams

Snake Drake Stutesman Sparrow Kim Todd Spider Katja and Sergiusz Michalski

Swan Peter Young Tiger Susie Green Tortoise Peter Young Trout James Owen

Vulture Thom van Dooren Walrus John Miller and Louise Miller Whale Joe Roman

Wolf Garry Marvin

Walrus

John Miller and Louise Miller

REAKTION BOOKS

For Dave Miller (19442013): il miglior tricheco

Published by

REAKTION BOOKS LTD

33 Great Sutton Street

London EC1V 0DX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

Copyright John Miller and Louise Miller 2014

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in China by 1010 Printing International Ltd

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 9781780233314

Contents

An Atlantic walrus resting on the ice.

The Walrus Emerges

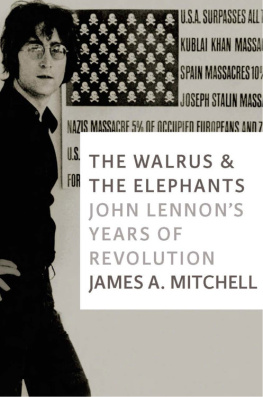

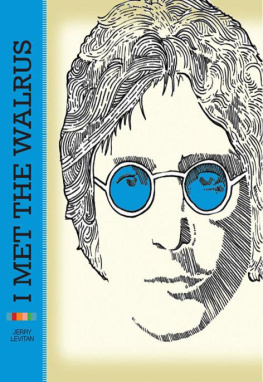

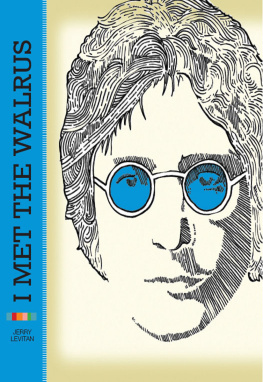

I am the walrus, claimed John Lennon in 1967, although no one is entirely sure what exactly he meant by that. To an extent the songs strangeness is lost now in its iconic status. It is easy to forget the oddity of the lyrics in this instantly recognizable classic. The walrus itself appears to us in a similar mixture of weirdness and familiarity. Its unique appearance makes it one of the most easily identified and anthropomorphized of animals. But the more you think about walruses, the stranger they seem. As one marine biologist put it, if walruses did not exist, inventing them might strain the imagination. Huge, lumbering and stinking, walruses exhibit a high level of social organization along with complex emotional lives and, perhaps more surprisingly, evidence of musicality and even creativity. Yet their behaviour and life cycle are still only partially understood. Scientists face significant obstacles in studying the walrus in its remote Arctic and sub-Arctic habitats. With global warming bringing radical changes to the geography of the North, time for further research into walruses in their natural environment may be limited.

Popular culture has made the walrus comical: whiskery, bleary-eyed and bellowing, a favourite uncle back from his regimental reunion ready for a nice long sleep in front of the fire; the genial fat man of the animal kingdom. The walrus is the Homer Simpson of the sea: slow, dense, fond of food and sleep, kindly and humorous. In nature documentaries walrus herds, known as haul-outs when out of water, form one of the defining images of the Arctic. Sometimes many thousands of animals may gather on an ice floe, dozing and grunting as they lie all over each other. For the most part walruses are peaceable, but they can be fierce when threatened. To early European sailors venturing into Arctic waters, these were terrifying monsters of the deep, intent on consigning the unwary to a watery grave. In fact, it was the walrus that had more cause for fear: its ivory tusks, oil-rich blubber and thick hide made it a prime target for commercial hunters. The malign sea monster became a lucrative commodity to be harvested with some profound, even catastrophic consequences.

A male Pacific walrus covered in tubercles (warty lumps) emerges from the sea. |

|

The walrus has been hunted for the benefit of mankind for millennia, but only in the last few hundred years has this threatened the species survival. To Arctic indigenous peoples, the walrus was, and for many remains, a staple food; a 1-ton animal that made a perfect meat-berg: food for humans and sled dogs and the raw materials for a range of essential manufactured items. Walrus rope may even have been used to hoist the stones of the great Gothic cathedral of Cologne.

Human activity limited the range of walrus populations somewhat, but prior to the beginning of commercial hunting, the walrus herds of the Arctic, sub-Arctic and more southerly latitudes probably numbered in the millions. It took large-scale exploitation by Europeans, beginning in the sixteenth century and peaking in the nineteenth, to seriously endanger the species. While indigenous inhabitants made use of the whole animal, commercial walrus hunters sought only hides, oil and ivory, and not always all of these. Walrus tusks became low-value items sought after by sailors for carvings and engravings (or scrimshaw) to fill their idle hours, while machine belting from walrus skins formed a widely used component of the Industrial Revolution. Ivory and hide gradually became eclipsed by oil; for parts of the nineteenth century London and other large cities were almost entirely lit by the blubber of sea mammals. Unlike indigenous hunting with harpoons, commercial hunting with firearms was extremely wasteful; many more walruses were killed than were recovered and used. Walruses were eradicated from many areas, leading to mass starvation among some indigenous peoples. Then, in the early twentieth century, marine mammal oil was largely replaced by mineral oil. There were no longer enough walruses left to make hunting profitable and, prompted by fears that the species would become extinct, protection measures were eventually introduced throughout the walruss range.