Copyright 2019 by Tom Holland

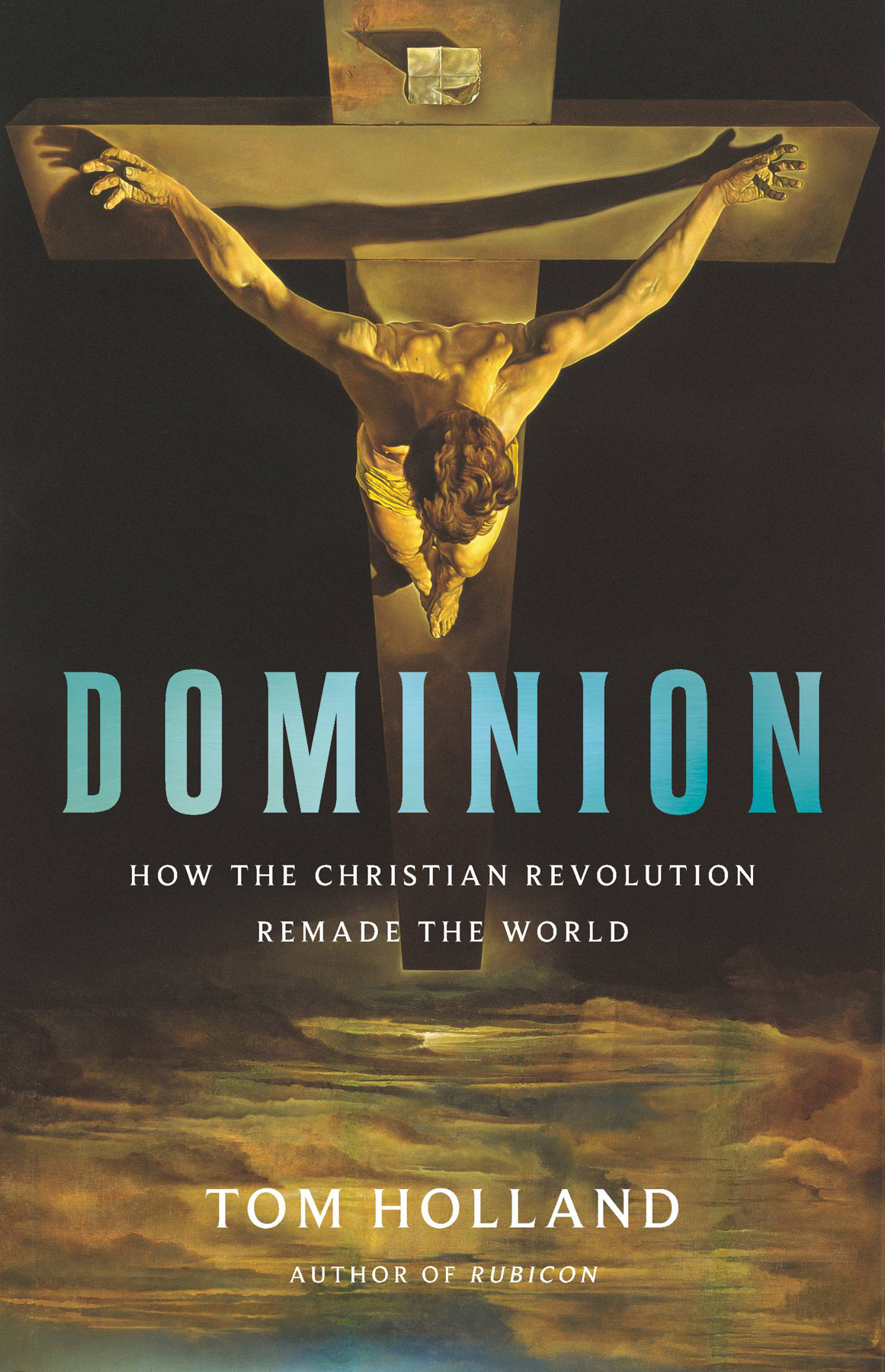

Cover design by Chin-Yee Lai

Cover images: Christ of St. John of the Cross, 1951 (oil on canvas), Dali, Salvador (190489) / Art Gallery and Museum, Kelvingrove, Glasgow, Scotland / CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection / Bridgeman Images; Chinnapong / Shutterstock.com

Cover copyright 2019 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Basic Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.basicbooks.com

Originally published in 2019 by Little, Brown in the United Kingdom

First US Edition: October 2019

Published by Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Basic Books name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019948347

ISBNs: 978-0-465-09350-2 (hardcover), 978-0-465-09352-6 (ebook)

E3-20191008-JV-NF-ORI

Dynasty: The Rise and Fall of the House of Caesar

In the Shadow of the Sword: The Birth of Islam and the Rise of the Global Arab Empire

The Forge of Christendom: The End of Days and the Epic Rise of the West

Persian Fire: The First World Empire and the Battle for the West

Rubicon: The Last Years of the Roman Republic

In memory of Deborah Gillingham. Much loved, much missed.

Love, and do as you will.

Saint Augustine

That you feel something to be right may have its cause in your never having thought much about yourself and having blindly accepted what has been labelled right since your childhood.

Friedrich Nietzsche

All you need is love.

John Lennon and Paul McCartney

S ome three or four decades before the birth of Christ, Romes first heated swimming pool was built on the Esquiline Hill. The location, just outside the citys ancient walls, was a prime one. In time, it would become a showcase for some of the wealthiest people in the world: an immense expanse of luxury villas and parks. But there was a reason why the land beyond the Esquiline Gate had been left undeveloped for so long. For many centuries, from the very earliest days of Rome, it had been a place of the dead. When labourers first began work on the swimming pool, a corpse-stench still hung in the air. A ditch, once part of the citys venerable defensive system, was littered with the carcasses of those too poor to be laid to rest in tombs. Here was where dead slaves, once they had been slung out from their narrow cells, picked the bodies clean. Nowhere else in Rome was the process of gentrification quite so dramatic. The marble fittings, the tinkling fountains, the perfumed flower beds: all were raised on the backs of the dead.

The process of reclamation, though, took a long time. Decades on from the first development of the region beyond the Esquiline Gate, vultures were still to be seen there, wheeling over a site named the Sessorium. This remained what it had always been: the place set aside for the execution of slaves.

Nevertheless, while the salutary effect of crucifixion on those who might otherwise threaten the order of the state was taken for granted, Roman attitudes to the punishment were shot through with ambivalence. Naturally, if it were to serve as a deterrent it needed to be public. Nothing spoke more eloquently of a failed revolt than the sight of hundreds upon hundreds of corpse-hung crosses, whether lining a highway or else massed before a rebellious city, the hills all around it stripped bare of their trees. Even in peacetime, executioners would make a spectacle of their victims by suspending them in a variety of inventive ways: one, perhaps, upside down, with his head towards the ground, another with a stake driven through his genitals, another attached by his arms to a yoke. It was this disgust that crucifixion uniquely inspired which explained why, when slaves were condemned to death, they were executed in the meanest, wretchedest stretch of land beyond the city walls; and why, when Rome burst its ancient limits, only the planting of the worlds most exotic and aromatic plants could serve to mask the taint. It was also why, despite the ubiquity of crucifixion across the Roman world, few cared to think much about it. Order, the order loved by the gods and upheld by magistrates vested with the full authority of the greatest power on earth, was what countednot the elimination of such vermin as presumed to challenge it. Criminals broken on implements of torture: who were such filth to concern men of breeding and civility? Some deaths were so vile, so squalid, that it was best to draw a veil across them entirely.

The surprise, then, is less that we should have so few detailed descriptions in ancient literature of what a crucifixion might actually involve, than that we should have any at all. these, over the course of Roman history, were the common lot of multitudes.

Decidedly not the common lot of multitudes, however, was the fate of Jesus corpse. Lowered from the cross, it was spared a common grave. Claimed by a wealthy admirer, it was prepared reverently for burial, laid in a tomb and left behind a heavy boulder.

The utter strangeness of all this, for the vast majority of people in the Roman world, did not lie in the notion that a mortal might become divine. The border between the heavenly and the earthly was widely held to be permeable. In Egypt, the oldest of monarchies, kings had been objects of worship for unfathomable aeons. In Greece, stories were told of a hero god

Divinity, then, was for the very greatest of the great: for victors, and heroes, and kings. Its measure was the power to torture ones enemies, not to suffer it oneself: to nail them to the rocks of a mountain, or to turn them into spiders, or to blind and crucify them after conquering the world. That a man who had himself been crucified might be hailed as a god could not help but be seen by people everywhere across the Roman world as scandalous, obscene, grotesque. The ultimate offensiveness, though, was to one particular people: Jesus own. The Jews, unlike their rulers, did not believe that a man might become a god; they believed that there was only the one almighty, eternal deity. Creator of the heavens and the earth, he was worshipped by them as the Most High God, the Lord of Hosts, the Master of all the Earth. Empires were his to order; mountains to melt like wax. That such a god, of all gods, might have had a son, and that this son, suffering the fate of a slave, might have been tortured to death on a cross, were claims as stupefying as they were, to most Jews, repellent. No more shocking a reversal of their most devoutly held assumptions could possibly have been imagined. Not merely blasphemy, it was madness.

Even those who did come to acknowledge Jesus as