Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in references to Kierkegaards works:

CA | The Concept of Anxiety, tr. R. Thomte and A. B. Anderson (Princeton University Press, 1980) |

CUP | Concluding Unscientific Postscript, tr. D. F. Swenson and W. Lowrie (Princeton University Press, 1941) |

EO | Either/Or, 2 vols., tr. D. F. and L. M. Swenson and W. Lowrie (Princeton University Press, 1959) |

FT | Fear and Trembling and Repetition, tr. H. V. and E. H. Hong (Princeton University Press, 1983) |

J | The Journals of Soren Kierkegaard, tr. A. Dru (Oxford University Press, 1938) |

PA | The Present Age, tr. A. Dru (Fontana Library, 1962) |

PF | Philosophical Fragments, tr. D. F. Swenson, rev. H. V. Hong (Princeton University Press, 1962) |

PV | The Point of View of my Work as an Author, tr. W. Lowrie (Harper and Row, 1962) |

SD | The Sickness unto Death, tr. H. V. and E. H. Hong (Princeton University Press, 1980) |

SLW | Stages on Lifes Way, tr. W. Lowrie (Schocken Books, 1967) |

Chapter 1

Life and character

Kierkegaard on more than one occasion likened genius to a thunderstorm that comes up against the wind. Whether or not he had himself partly in mind when making the comparison, it seems in retrospect to have been an apt one so far as his own intellectual career was concerned. Like Marx and Nietzsche, he emerges as one of the outstanding iconoclasts and rebels of 19th-century thought, writers whose works were composed in conscious opposition to the prevailing assumptions and conventions of their age and whose crucial contentions only achieved widespread recognition after they were dead.

In Kierkegaards case recognition was particularly slow in coming. He wrote in Danish, and to his Danish contemporaries he was in his own eyes at least a superfluous figure; either they did not read what he wrote or else, if they did, they misunderstood its underlying import. Even when, not very long after his death in 1855, German translations began to appear, they made little initial impact, although they were to become increasingly influential in Central Europe during and immediately after the First World War. It was, however, largely through its association with existentialism, which emerged as a well-publicized philosophical movement in the 1930s and 1940s, that his name can first be said to have acquired the kind of international prominence it indisputably enjoys today. As a thinker he may be regarded as awkward, controversial, difficult to classify; but he is certainly not ignored.

Such posthumous fame would in fact have caused Kierkegaard no surprise. He himself confidently predicted it, foreseeing a time when his books would be the subject of serious study and when he would be applauded for the novelty and depth of the insights they contained. Whether, on the other hand, it would have afforded him undiluted satisfaction is a different matter. When he referred to the prospect he treated it as an occasion, not for self-congratulation, but for sardonic comment. For the persons whose approbation he anticipated were those he labelled professors; in other words, future members of the selfsame academic institutions which during his lifetime were the target of some of his sharpest criticism. Admittedly his opinions on this score, like the pronounced antipathy he came to feel towards the Church, were voiced most stridently towards the end of his career. None the less, his hostility to the academic establishment was continuous with an earlier and deep-rooted suspicion of something that he believed to be endemic to the intellectual climate of his period. This was its preoccupation with what he called the illusions of objectivity, exhibiting itself, on the one hand, in a tendency to smother the vital core of subjective experience beneath layers of historical commentary and pseudo-scientific generalization and, on the other, in a proneness to discuss ideas from an abstract theoretical viewpoint that took no account of their significance for the particular outlooks and commitments of flesh-and-blood human beings. All Kierkegaards writings, in one way or another, bore witness to the necessity of affirming the integrity of the individual in the face of such trends, and the same can be said to have been true of his life. His work and his personal existence were indeed inseparably intertwined, the connections between the two being faithfully recorded in the copious journals which he kept from the age of 21 onwards and which throw a vivid light upon the labyrinthine recesses of his strange and complex disposition.

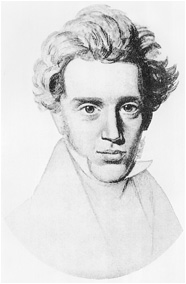

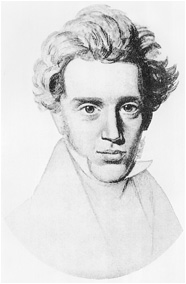

Portrait of Kierkegaard. Unknown artist.

Sren Aabye Kierkegaard was born in Copenhagen on 5 May 1813. He was the seventh child of Michael Pedersen Kierkegaard, a retired hosier who had been released from serfdom in his youth and who had since become relatively wealthy, partly through his own efforts but also as a result of inheriting a considerable fortune from an uncle. Kierkegaards mother, whom his father had married after the early death of his first wife, had been the latters maid; she was illiterate and appears to have played a somewhat shadowy part in her sons upbringing. His father, by contrast, was a dominant influence. Self-educated and shrewd in business, he was at the same time a devout member of the Lutheran Church with a strong belief in duty and self-discipline. Kierkegaard was later to recall the absolute obedience that was demanded of him as a child, but it was not this that made the greatest impression upon him. More potent, at any rate in its subsequent effects, was the atmosphere of gloom and religious guilt that emanated from a parent who believed that both he and his family lay under a mysterious curse and who, notwithstanding his worldly success, lived in constant expectation of divine retribution. Thus, in a retrospective entry in his journals, his son could speak of the dark background which, from the very earliest time, was part of my life and recollect the dread with which my father filled my soul, his own frightful melancholy, and all the things in this connection which I do not even note down (J 273).

Although he was never at any stage one to underestimate the personal disabilities and difficulties that beset him, there is a poignancy about such remarks which makes it understandable that Kierkegaard should have stigmatized the manner in which he had been brought up as insane. Even so, his feelings towards the man who evoked them were ambivalent: he was fascinated by his fathers vivid if morbid imagination, appears to have been impressed by his intellect and powers of argument, and always remained bound to his memory by some profound emotional affinity that involved a strange mixture of love and fear.

Nytorv (New Square), Copenhagen, in 1865. The town where Kierkegaard was born.

If his life at home was conducted in what one of his childhood companions portrayed as a mystical twilight of strictness and eccentricity, Kierkegaards career at the private school he attended does not seem to have afforded him much in the way of relief. As a boy he was physically weak and maladroit, and at the same time acutely self-conscious about what he felt to be his unprepossessing appearance; in consequence, he played no part in games and tended to be a natural prey to bullies. He was, however, far from being defenceless in other respects. He quickly became aware of his superior intelligence, admitting later that this provided him with an effective weapon by which to protect himself against those who threatened him. He had a sharp and wounding tongue, was perceptive in spotting the vulnerable points of others, and from all accounts was an adept and provocative tease, capable of reducing members of his class to tears. As a result, he put a distance between himself and those around him, a lonely, introverted figure who inspired apprehension rather than affection. The picture painted by his contemporaries at school may not be an altogether attractive one. Nevertheless, it is not without intimations of the angular independence of mind and the talent for ridicule that were to be amongst his most immediately striking characteristics as an adult. In 1830, at the age of 17, Kierkegaard enrolled as a student at the University of Copenhagen. Initially things went well enough. During his first year he covered preliminary courses in a wide range of subjects; they included Greek and Latin, history, mathematics, physics, and philosophy, and he passed all the relevant examinations with distinction. He then began reading for a degree in theology, following in the footsteps of his academically gifted but rather priggish elder brother, Peter; the latter had already completed the course in less than the usual time and was now working for a doctorate in Germany. In Srens case, however, matters were not to proceed so smoothly. His progress towards the degree gradually lost momentum and by 1835 he was writing to a friend that taking the course was an occupation that did not in the least interest him; he preferred a free and perhaps a somewhat indefinite study to the