Darwins Most Wonderful Plants

Darwins Most Wonderful Plants

DARWINS BOTANY TODAY

KEN THOMPSON

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by

Profile Books

3 Holford Yard, Bevin Way

London WC1X 9HD

www.profilebooks.com

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Typeset in Bembo

to a design by Henry Iles.

Copyright Ken Thompson 2018

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 9781788160285

e-ISBN 9781782834366

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

The Secrets of Plants

If you were writing a book about almost any aspect of the natural world, you could do a lot worse than start with Charles Darwin. And not only because he was the author of The Origin of Species, a book that ultimately explains everything. Darwins consuming interest in evolution fed, and in turn was fed by, an almost obsessional curiosity about natural history.

Much of this extraordinarily broad interest in the natural world, its true, was motivated by a search for evidence for evolution by natural selection. To take one small example, a problem that bothered Darwin (and was used as a stick to beat him by his critics) was the very wide distribution of some kinds of animals and plants. How to explain the presence of a species in two or more widely separated locations (and sometimes nowhere in between), other than that was where a Creator had chosen to put them? Part of the answer lies in plate tectonics, but that discovery lay over a century in the future (one problem with being ahead of your time is having to wait for others to catch up).

Another part of the answer is dispersal: the underappreciated ability of species to travel very large distances, often in unexpected ways. To see if seeds might be dispersed by ocean currents, Darwin spent over a year testing the ability of seeds of many species to survive immersion in sea water. He also suspected that seeds might disperse in mud stuck to the feet of wading birds, many of which were known to migrate over huge distances. But are there seeds in mud? Nothing for it but to find out:

I have tried several little experiments, but will here give only the most striking case: I took in February three table-spoonfuls of mud from three different points, beneath water, on the edge of a little pond; this mud when dry weighed only 6 ounces; I kept it covered up in my study for six months, pulling up and counting each plant as it grew; the plants were of many kinds, and were altogether 537 in number; and yet the viscid mud was all contained in a breakfast cup! Considering these facts, I think it would be an inexplicable circumstance if water-birds did not transport the seeds of fresh-water plants to vast distances, and if consequently the range of these plants was not very great.

Thats it Darwin had no more to say on the subject, but those few words had fired the starting gun for the study of soil seed banks, now a thriving sub-discipline of plant biology and ecology.

Sometimes Darwin seemed to stumble on a whole area of biology almost by accident. For example:

I had originally intended to have described only a single abnormal Cirripede [barnacle] from the shores of South America, and was led, for the sake of comparison, to examine the internal parts of as many genera as I could procure.

Describing one barnacle, one imagines, would hardly have taken him too long, but that entailed a comparison with other barnacles, one thing led to another and the eventual result, taking eight years work, was a two-volume monograph on this enormous class of crustaceans, running to well over 1,000 pages.

Already, we can begin to see some characteristic features of the Darwinian approach: an astonishing capacity for hard work (Thomas Edisons dictum that Genius is one per cent inspiration, ninety-nine per cent perspiration could easily have described Darwin), and an unwillingness to take anything on trust. He was unimpressed by mere scientific reputation, but once persuaded that someone knew what they were talking about, he was happy to correspond with anyone from gardeners to pigeon fanciers. But if Darwin wanted to know anything, his usual response was lets find out, and woe betide any idea that failed to stand up to experimental scrutiny. Thus his attitude to homeopathy, as fashionable among the scientifically illiterate then as it is now, was blunt:

[It is] a subject which makes me more wrath, even than does clairvoyance. Clairvoyance so transcends belief, that ones ordinary faculties are put out of the question, but in homopathy common sense and common observation come into play, and both these must go to the dogs, if the infinitesimal doses have any effect whatever. How true is a remark I saw the other day by Quetelet, in respect to evidence of curative processes, viz. that no one knows in disease what is the simple result of nothing being done, as a standard with which to compare homopathy, and all other such things.

Another consistent feature of Darwins work was that, irrespective of his original motivation, he tended to fall in love with whatever he happened to be working on at the time, until it became an overwhelming passion. The barnacles were no exception; how else to explain the eight years he spent working on them? After a period of ill health, he wrote in March 1849 that he was looking forward to getting back to work on his beloved barnacles. Mind you, Darwin was as capable as the rest of us of biting off more than he could chew. Towards the end of 1849, theres a hint that barnacles are less fun than they were: my daily two and a half hours at the barnacles is fully as much as I can do of anything which occupies the mind, and by 1852 the love affair was well and truly over: I am at work at the second volume of the Cirripedia, of which creatures I am wonderfully tired. I hate a barnacle as no man ever did before, not even a sailor in a slow-sailing ship. By 1855 his relief is palpable that I have at last quite done with the everlasting barnacles.

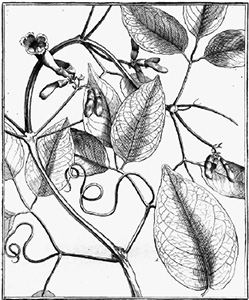

Barnacles may have been one of Darwins early passions, but later that enthusiasm was transferred to other branches of natural history. Many of these later love affairs were botanical, initially at least because plants were convenient experimental material. As his son Francis put it after his fathers death, Darwin determined to learn about plants as he used them in the building of his theory, but later on the tables were turned, and the theory served him as a powerful engine to break still further into the secrets of plants. Not that Darwin ever pretended to be a botanist; he had no professional training in the subject, and was amused to receive accolades from real botanists and botanical institutions. But Darwins love of the natural world knew no boundaries, and he was as capable of falling in love with a plant as he was with a barnacle or an earthworm.

One of the great advantages of knowing little or nothing about a subject, of course, is that you can approach it with fresh eyes, and a mind free of (often erroneous) preconceived ideas. But ignorance can only take you so far, and it was his (and our) great good fortune that Darwins botany was guided throughout his life by Joseph Hooker, Director of Kew Gardens, a man who really did know his botany. Indeed, if you want a biography of Darwin, one that gives you a real feel for how he spent his time, his correspondence with Hooker would do as well as anything else.

Next page