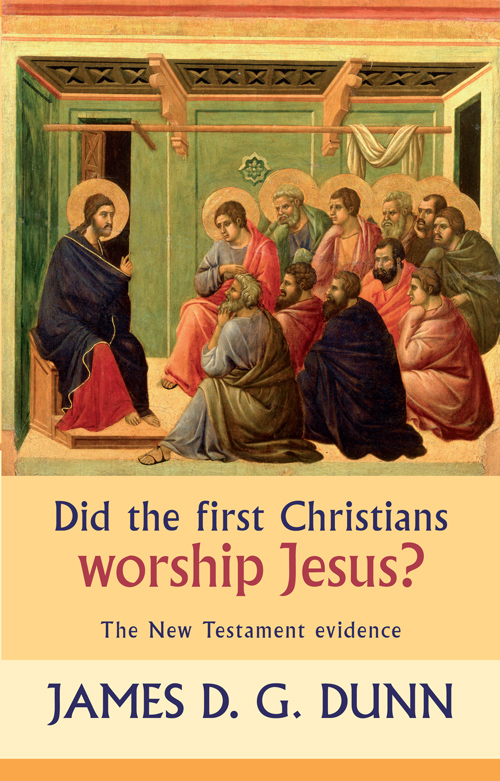

James D. G. Dunn is Emeritus Lightfoot Professor of Divinity, Durham University, and is the author of numerous ground-breaking works in New Testament Studies. His most recent publications include A New Perspective on Jesus: What the Quest for the Historical Jesus Missed (Baker/SPCK, 2005), Jesus Remembered (Eerdmans, 2003), The Cambridge Companion to St Paul (Cambridge University Press, 2003) and The Theology of Paul the Apostle (Eerdmans/T&T Clark, 1997).

To

Richard Bauckham

and

Larry Hurtado,

partners in dialogue

Copyright James D. G. Dunn 2010

First published in Great Britain in 2010 by

Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge

36 Causton Street

London SW1P 4ST

Published in 2010 in the United States of America by

Westminster John Knox Press

100 Witherspoon Street

Louisville, KY 40202

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 1910 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Scripture quotations marked NRSV are taken from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, Anglicized Edition, copyright 1989, 1995 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

All other Scripture quotations are the authors own translation.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-0-281-05928-7 (U.K. edition)

E-ISBN 978-0-281-06500-4 (alk. paper)

United States Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Dunn, James D. G., 1939

Did the first Christians worship Jesus? : the New Testament evidence / James D. G. Dunn.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. 152) and indexes.

ISBN 978-0-664-23196-5 (alk. paper)

1. Jesus ChristCultHistory. 2. Worship in the Bible. 3. Jesus ChristDivinityHistory of doctrinesEarly church, ca. 30600. 4. Bible. N.T.Theology. I. Title.

BT590.C85D86 2010

232.809015dc22

2009049234

Typeset and e-book by Graphicraft Limited, Hong Kong

Printed in Great Britain by MPG

Produced on paper from sustainable forests

Contents

ABD | D. N. Freedman (ed.), Anchor Bible Dictionary (6 vols; New York: Doubleday, 1992) |

ALD | C. T. Lewis, A Latin Dictionary (Oxford: Clarendon, 1879) |

BDAG | W. Bauer, A GreekEnglish Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature , ET W. F. Arndt and F. W. Gingrich (eds), 3rd edition revised by F. W. Danker (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000) |

BCE | Before the Christian Era, or, Before the Common Era |

BZNW | Beihefte zur Zeitschrift fr die neutestamentliche Wissenschaft |

CE | Christian Era, or, Common Era |

EKK | Evangelisch-katholischer Kommentar zum Neuen Testament |

ET | English translation |

FS | Festschrift, volume written in honour of |

HNT | Handbuch zum Neuen Testament |

HUCA | Hebrew Union College Annual |

ICC | International Critical Commentary |

JJS | Journal of Jewish Studies |

JQR | Jewish Quarterly Review |

JR | Journal of Religion |

JSJ Supp | Journal for the Study of Judaism Supplement Series |

JSNT | Journal for the Study of the New Testament |

JSNTS | JSNT Supplement Series |

JSOT | Journal for the Study of the Old Testament |

JTS | Journal of Theological Studies |

LCL | Loeb Classical Library |

LXX | Septuagint |

MT | Masoretic Text |

NIGTC | New International Greek Testament Commentary |

NIV | New International Version (1978) |

NJB | New Jerusalem Bible (1985) |

NovT | Novum Testamentum |

NRSV | New Revised Standard Version (1989) |

NT | New Testament |

NTS | New Testament Studies |

OCD 3 | S. Hornblower and A. Spawforth (eds), The Oxford Classical Dictionary (3rd edition; Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2003) |

ODCC | F. L. Cross and E. A. Livingstone (eds), The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2nd edition; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983) |

OT | Old Testament |

OTP | J. H. Charlesworth (ed.), The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha (2 vols; London: Darton, Longman & Todd, 1983, 1985) |

REB | Revised English Bible (1989) |

SNTSMS | Society for New Testament Studies Monograph Series |

TDNT | G. Kittel and G. Friedrich (eds), Theological Dictionary of the New Testament (ET; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 196476) |

TDOT | G. J. Botterweck and H. Ringgren (eds), Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament (ET; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1974 2006) |

WBC | Word Biblical Commentary |

WUNT | Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament |

The status accorded to or recognized for Jesus is the key distinctive and defining feature of Christianity. It is also the chief stumbling block for inter-faith dialogue between Christians and Jews, and between Christians and Muslims. Jew and Muslim simply cannot accept the divine status of Jesus as the Son of God, which Christians regard as fundamental to their faith. The Christian understanding of God as Trinity baffles them. To regard Jesus as divine, as worthy of worship as God, seems to them an obvious rejection of the oneness of God, more a form of polytheism than a form of monotheism. And truth to tell, many Christians also find the understanding of God as Trinity baffling. The confession of the Trinity in terms of essence (or substance) makes too little sense, apart from the Greek philosophical categories that the language presupposes, for it to be very meaningful for most of those who repeat the Nicene Creed. And the classic creedal distinction between different persons of the Godhead, when person is understood in its everyday sense, invites the perception of God in tri-theistic rather than Trinitarian terms, as three and distinct individual persons.

In view of this, it may be helpful to look back to the beginning of the process that resulted in the formulation of the Christian doctrine of the Trinity, and in doing so to clarify what lay behind the confession of Jesus as the Son of God in Trinitarian terms. The language of essence/substance and person was, of course, carefully chosen and the usage of these terms was finely tuned by the controversies over the precise status of Jesus that racked the first few centuries of Christianity. But most Christians and most inter-faith dialogue would find it hard to recover and to appreciate that fine-tuning without an intensity of immersion in ancient philosophical debates that few could contemplate or have time for. Perhaps, then, a more fruitful way forward would be to inquire behind the process that has given Christianity its creedal confessions, to attempt some closer examination of the beginning of the process what it was that launched the process, what it was that made Christians want to speak of Jesus in divine terms, what it was that led to the worship of Jesus as God.