W HEN I WAS a child, I grew up outside. My sister and I built forts. We dug holes. We made trails and swung on vines. The indoors was a place reserved for sleeping, or for playing when it got so cold outside that our fingers seemed as though they might fall off (we lived in rural Michigan where that could happen well into the spring). But the outdoorsthats where we lived.

In the time since our childhood, the world has fundamentally changed. Kids today grow up primarily indoors, their lives punctuated by short bouts of movement from one building to another. This is not hyperbole. The average American child now spends 93 percent of his or her time in a building or a vehicle. Nor is it just American kids. The data are similar for children in Canada as well as in much of Europe and Asia. I mention this not to bemoan the state of the world but instead to suggest that this transition reveals a radical new stage in the cultural evolution of our species. We have become, or are becoming, Homo indoorus, the indoor human. We now live in a world defined by the walls of our houses and our apartments, which are more connected to hallways and other homes than to the outdoors. In light of this shift, it seems as though we should make it a priority to know which species are living indoors with us and how they affect our well-being. But, in reality, weve only just scratched the surface.

Weve known about the existence of other life in our homes since the earliest days of microbiology. At that time, it was studied by one man, Antony van Leeuwenhoek, who uncovered an astonishing number of life-forms in his home, on his body, and within the homes and bodies of his neighbors. He studied these species with a sense of obsessive joy and even awe. During the century after his death, no one really took up where he left off. Then, once it was finally discovered that some of the species in our homes could make us sick, the focus turned to those species, the pathogens. What followed was a huge shift in public perception, wherein we began to think of the species living alongside us, when we thought of them at all, as bad, as something we should kill. That shift saved lives, but it went too far, and as a result, no one ever really paused to study or appreciate the rest of the life in our homes. A few years ago, all of that changed.

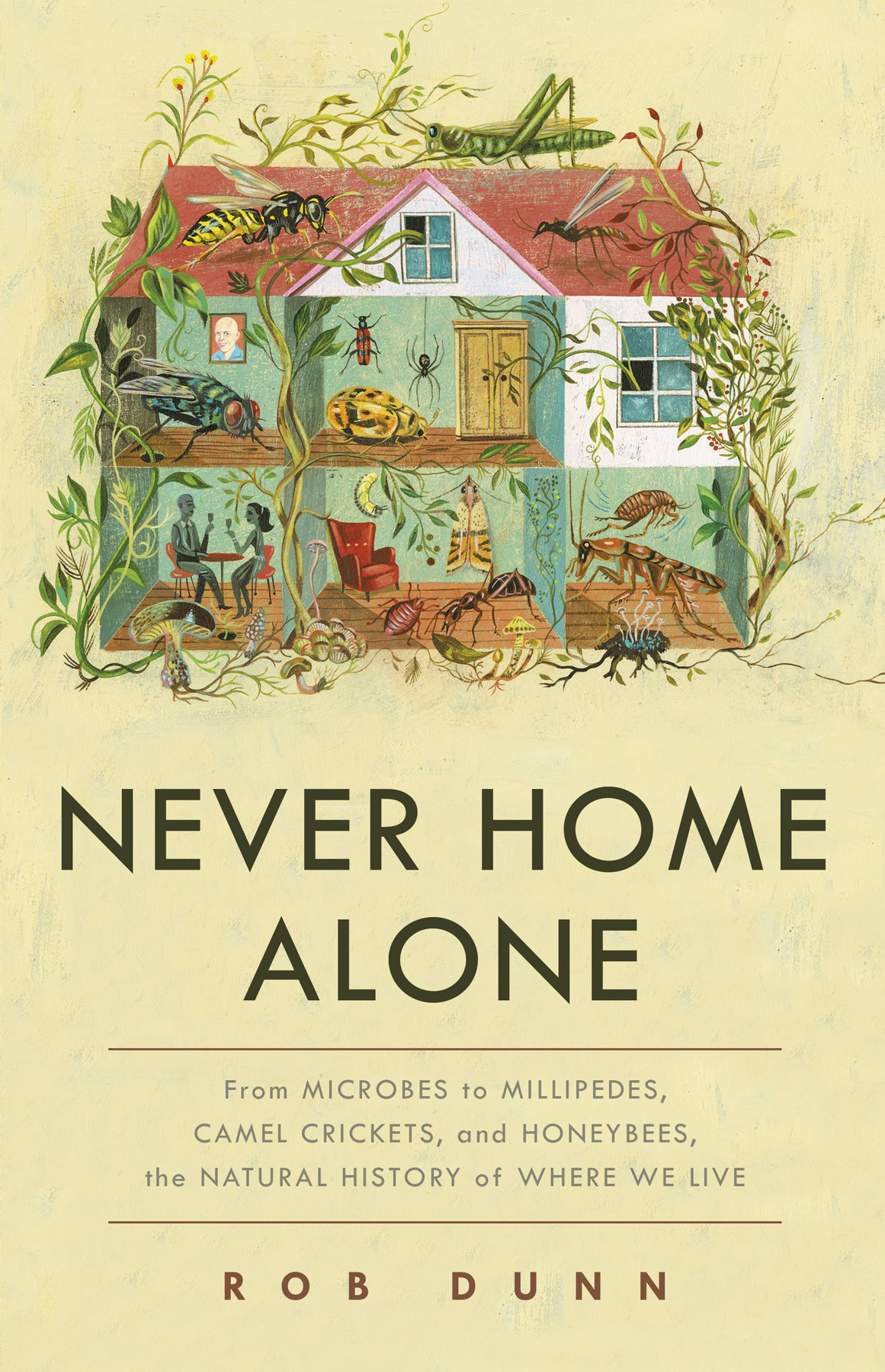

Research groups, including my own, began to seriously reconsider the life in our homes. We began to study the life in homes in the way one might inventory a rain forest in Costa Rica or a grassland in South Africa. When we did, we were in for a surprise. We expected to find hundreds of species; instead, we discovereddepending on just how we do the mathupward of two hundred thousand species. Many of these species are microscopic, but others are larger and yet nonetheless overlooked. Breathe in. Inhale deeply. With each breath you bring oxygen deep into the alveoli of your lungs, along with hundreds or thousands of species. Sit down. Each place you sit you are surrounded by a floating, leaping, crawling circus of thousands of species. We are never home alone.

Just what kinds of species are living alongside us? There are, of course, the big species, the visible life. Around the world, tens, perhaps hundreds, of different kinds of vertebrates and even more kinds of plants can be found in homes. Far more diverse than the vertebrates and the plants, and still visible to the naked eye, are the arthropods, the insects and their kin. More varied than the arthropods, and often though not always smaller, are the species of the kingdom Fungi. Smaller than the fungi, and entirely invisible to the naked eye, are the bacteria. More species of bacteria have been found in homes than there are species of birds and mammals on Earth. Smaller still than the bacteria are the viruses, both those that infect plants and animals as well as the specialized viruses, the bacteriophages, that attack bacteria. We tally all of these different kinds of life independently. But the truth is they often arrive in our homes together. Our dogs, for instance, walk in our front doors carrying fleas in the guts of which live fungi and bacteria on which live bacteriophages. When the author of Gullivers Travels, Jonathan Swift, noted that each flea hath smaller fleas that on him prey, he didnt know the half of it.

Y OU MIGHT, IN HEARING about all this life, be inspired to go home and scrub, and then scrub some more. But here is the other surprise. As my colleagues and I have looked at the life in homes, we have discovered that many of the species in the most diverse homes, the homes fullest of life, are beneficial to us, necessary even. Some of these species help our immune systems to function. Others help to control and compete with pathogens and pests. Many are potential sources of new enzymes or drugs. A few can help ferment new kinds of beers and breads. And thousands carry out ecological processes of value to humanity such as keeping our tap water free of pathogens. Most of the life in our homes is either benign or good.

Unfortunately, just as scientists have begun to discover the goodness, the necessity even, of many of the species in our homes, society at large has stepped up efforts to sterilize the indoors. Our increasing human efforts to kill the life in homes have unintended and yet very predictable consequences. The use of pesticides and antimicrobials, along with ongoing attempts to seal off homes from the rest of the world, tends to kill off and exclude beneficial species that are also susceptible to such assaults. In their place, we unknowingly aid resistant species such as German cockroaches and bed bugs and deadly MRSA bacteria (the methicillin-resistant species of