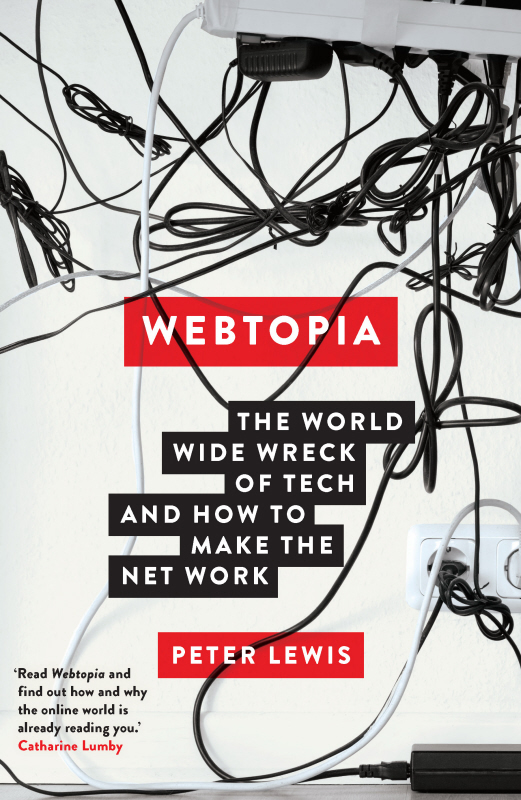

PETER LEWIS is the executive director of Essential, a progressive research and communications company. He has worked previously as a journalist and political advisor and is a regular columnist for Guardian Australia.

Also by Peter Lewis:

The Convert: A fans journey from League to AFL

Tales from the New Shop Floor: Inside the real jobs of the information economy

Ship of Tools: The best of Workers Onlines first 100 issues

A NewSouth book

Published by

NewSouth Publishing

University of New South Wales Press Ltd

University of New South Wales

Sydney NSW 2052

AUSTRALIA

newsouthpublishing.com

Peter Lewis 2019

First published 2019

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

ISBN: 9781742236353 (paperback)

9781742244464 (ebook)

9781742248929 (ePDF)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia

Design Josephine Pajor-Markus

Cover design Peter Long

Cover image aristotoo/iStock

All reasonable efforts were taken to obtain permission to use copyright material reproduced in this book, but in some cases copyright could not be traced. The author welcomes information in this regard.

CONTENTS

Ill fares the land, to hastening ills a prey, Where wealth accumulates, and men decay.

Oliver Goldsmith, The Deserted Village

Either our lives become stories or theres just no way to get through them.

Douglas Coupland, Generation X

INTRODUCTION

In 1989 I played a small role in a series of events that changed world history. Sitting in a dimly lit newsroom in the hours between midnight and dawn, I was one of the first people in Australia to bear witness to the end of the Cold War. I was a cadet journalist learning what was still a coveted trade, one where you were anointed an arbiter of objective truths and your work was so important it was inscribed with your personal byline.

In reality there was no glamour in the midnight to dawn shift on the AAP broadcast desk. The work was to take foreign wire copy and rewrite it for distribution to local radio stations. An experienced copy-taster would monitor the flow of news coming through the international wire services like Reuters and Associated Press and flick the best pieces over a boxy local intranet to be cut down to a few short sentences and converted into present tense ready for live reads the next morning. It was craft rather than art, but it taught a young writer the discipline of being clean and tight.

It was during one of these overnight shifts that the Eastern Bloc began to collapse before me on my screen. A long-running strike by Lech Walesas Solidarity movement brought down Moscows Polish puppets. Within weeks the Hungarian Communist Party had ceded power. Then the Berlin Wall was pulled apart brick by brick as the Stasi headed for the hills. The Velvet Revolution put a playwright in charge of the Czechs before the Ceausescus were left lying on blood-stained snow in Bucharest. It became a procession of events; every night I turned up to work expecting to write a new page of history in four sharp pars.

Of course the only thing special about me was the seat I was occupying. I was part of an institution that controlled the distribution of scarce information. On a night when history was being made on the other side of the world, I was the filter of that information for millions of people. AAP was full of stories of SNAFUs surrounding the control of this precious information. Like the sports sub who spiked the Ben Johnson drugs story, meaning Australian radio missed the biggest yarn of the Seoul Olympics. The flow of global information literally came down to the acts and omissions of individuals. Yes, the government would have been monitoring events by diplomatic cables and ABC radio had reporters on the ground. But even allowing for this, a 23-year-old in the first months of his career determined how millions of Australians learned the Cold War was over.

#

Today 1989 feels like another universe. If the Wall came down now it would be live-streamed on Facebook, bricks would be up for sale on eBay within hours, celebrities would be tweeting inspirational aphorisms to #teardownthewall. The Berlin crowds would have organised themselves on an encrypted WhatsApp group to coordinate their activity before they hit the streets. No doubt there would have been online political actions with millions clicking petitions targeting their leaders and demanding they stand aside. The only role for an AAP overnight sub would be to attempt to curate the social media content into an online news story, carefully designed to maximise views and, more importantly, shares. And that work would probably wait until morning when there would be no need to pay anyone overnight penalty rates.

The young man sitting astride the broadcast media through those nights of revolution is a neat symbol of the world that was. It was a world dominated by institutions that derived their power from their control of scarce information not just the media, but government agencies, businesses, industry associations and unions. The structures of our society in 1989 resembled a series of broadcast towers that derived their power from their ability to reach a trusting public eagerly awaiting their signals.

Whereas information then was scarce and was directly transmitted from producer to receiver, today it is multi-dimensional and ubiquitous, peppering us from all directions. The broadcast tower has been replaced by a complex fabric of networks, each individual in control of the flow of information in and out. Where once we were passive receivers, now we can be active participants in these flows. Whether we are sharing content on Facebook, posting an opinion on Twitter, endorsing a hotel on TripAdvisor or rating a driver on Uber, technology has transformed our world and our role in it by bringing us closer to the action.

Meanwhile the hubs of authority that dominated the industrial age are in decline. Trust in public institutions has collapsed, membership of groups is plummeting, the media is now an industry in seemingly terminal decline. All have been challenged by the freer flow of information on the internet and the applications that have emanated from it. While these former centres of authority tried to stem their waning influence, the shift to a flatter, more networked world based around these rapidly evolving technologies is now our reality.

This is not a book about the internet per se; I am no more a technology expert than I was an expert on Cold War politics back in 1989. Im not even sure what to call the thing I am describing. The internet? Our online life? Virtual reality? Network technology? The information economy? Cyber-whatever? All these terms seem interchangeable and depend on the context and motivations of the user. What I am really referring to are the flattened networks that technological change has driven and continues to drive. If we need to give it a name, lets use the least precise, least techie term Ive come across lets call it the web.

Next page