Table of Contents

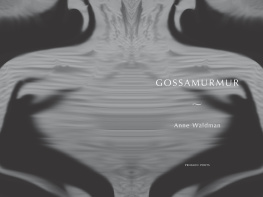

BOOKS, CHAPBOOKS & COLLABORATIONS BY ANNE WALDMAN

On the Wing

O My Life!

Giant Night

Baby Breakdown

No Hassles

West Indies Poems

Life Notes

Self-Portrait (with Joe Brainard)

Fast Speaking Woman

Memorial Day (with Ted Berrigan)

Journals & Dreams

Sun the Blonde Out

Shaman/Shamane

Polar Ode (with Eileen Myles)

Countries

Cabin

First Baby Poems

Sphinxeries (with Denyse Du Roi)

Makeup on Empty Space

Invention (with Susan Hall)

Skin Meat Bones

The Romance Thing

Den Monde in Farbe Sehen

Blue Mosque

Tell Me About It: Poems for Painters

Helping the Dreamer: New &

Selected Poems

Her Story (with Elizabeth Murray)

Not a Male Pseudonym

Lokapala

Fait Accompli

Troubairitz

Iovis: All Is Full of Jove

Kill or Cure

Iovis II

La Donna Che Parla Veloce

Au Lit/Holy (with Eleni Sikelianos

& Laird Hunt)

Young Manhattan (with Bill Berkson)

Polemics (with Anselm Hollo &

Jack Collom)

Homage to Allen G. (with George

Schneeman)

Kin (with Susan Rothenberg)

One Voice in Four Parts

(with Richard Tuttle)

Marriage: A Sentence

Zombie Dawn (with Tom Clark)

Dark Arcana/Afterimage or Glow

In the Room of Never Grieve:

New & Selected Poems

Fleuve Flneur (with Mary Kite)

for all the turners of the Wheel

That I am a singer of little songs,

Proves that I have learned to read the world as a book.

MILAREPA

so that, living within,

you beget, self-out-of-self,

selfless,

that pearl of great price.

H. D.

FROM THE WALLS DO NOT FALL

Acknowledgments

Milarepa quote from Technicians of the Sacred, Editor: Jerome Rothenberg, University of California Press, Berkeley, California.

With gratitude to the Civitella Ranieri Center, Umbria, Italy, to the Naropa University Study Abroad Programs, Boulder/Bali, and to the Foundation for Contemporary Performance Arts for support and time to work on this book.

A page of this text was first published in The Poetry Project Newsletter.

And with gratitude to my Buddhist teachers the Dorje Dradul and Jadtral Rinpoche whose teachings grace these pages.

Thanks also to my editor at Penguin, Paul Slovak, and to my husband Ed Bowes for their ongoing perspicacity, and to Ambrose Bye, always.

A Vajradhatu or Diamond World mandala, based on a ninth-century Tibetan version.

Authors Introduction

The magnificent stupa of Borobudur in Java, Indonesia, is an architectural provocation. It begs numerous questions, and seems to be a still-active container as well as a mandala or diagram of an advanced philosophy that invites a spiritual and psychological voyage for the visitor.

The stupa form originated in pre-Buddhist India as a burial tumulus or mound of earth surmounted by a wooden pillar symbolizing the frission between heaven, earth, and the underworld. The pole was seen as an energizing conductor, an antennae for a power spot that might benefit both the environment and those who witnessed it. The historical Buddha, it is said, requested to be buried under a stupa. After his cremation his ashes were placed under eight stupas at different places associated with principal events of his life. As a burial marker or reliquary the stupa then becomes a site of respect and spiritual practice. Stupas might also have commemorated particular sacred events, or have been constructed by wealthy rulers or patrons to gain religious merit. Ancient stupas are found in Java and other parts of Indonesia as well as India, Tibet, Nepal, and now in Europe, Canada, and Americaplaces where Buddhism is flourishingon a decidedly more modest scale than Borobudur. Yet the recently completed Great Stupa of Dharmakaya in Red Feather Lakes, Coloradobuilt with cement to last at least a thousand yearsis a remarkably complex and stunning achievement. The pyramids of Egypt and Central and South America come to mind as resonant sites of power and influence that often honor a ruler or king, in addition to the ziggurats of Mesopotamia. The most spectacular religious monuments of the third millennium B.C.E. are the impressive ziggurats, a best preserved example being the ziggurat of the moon goddess Nanna at Ur (in what is contemporary Iraq). Height and a feeling of aspirationascensionhas been associated with religious edifices for centuries. It was this particular upward spiritual motion at Borobudur that inspired the writings of this book.

Designed as both mandala or psychological map for the Buddhist pilgrim, as well as a spiritual challenge to the curious layperson or secular aesthete, Borobudur was built on a hill that sits on Javas lush Kedu plain. It has a long and complex history and was almost lost until its discovery in the nineteenth century, a process which took over fifty years, instigated in part by Lieutenant-Governor Thomas Stanford Raffles, the first colonial ruler to take an interest in Javanese antiquities and history. Raffles, an unusual colonialist employee, being both scholar and writer, dispatched H.C. Cornelius, a Dutch engineer, to the ruin, which took a month and half for two hundred men to uncover. It had been piled high with dirt and overgrown with centuries of thick vegetation. Subsequent staggered recovery and reconstruction took many years.

Buddhism enjoyed only a short period of popularity in central Java and was less practiced than Hinduism. This radical atheistic tradition had been introduced from India to China along the famed Silk Route in the first century C.E. Later a sea-link was forged between India and China, opened up by Indonesian sailors who had several centuries of experience in maritime trade with other parts of Southeast Asia and India. Buddhist pilgrims traveled through the archipelago with increased frequency during the seventh and eighth centuries. Java and Sumatra were major centers of international Buddhist scholarship during this expansive cross-cultural period.

Buddhism was linked to the Sailendraor Lords of the Mountainfamily, which for a century supported Buddhist monuments and study in Java. Most likely construction of Borobudur began in 760 C.E. and was completed about 830. It is made up of some million stones hauled up from a nearby riverbed, weighing one hundred kilograms each. This required enormous manpower. Evidence indicates that the majority of workers were farmers and part-time artisans. They carved the reliefs, plastered and painted the final monument. Clearly material support and stimulus came from the Sailendra ruler of the time, but the workers were in no way slaves to the project. Archeological evidence shows that a strong community of laymen and women as well as clergy lived in Borobudurs environs and were inspired by the task at hand for several generations. Questions remain as to why the temple was nearly abandoned within seventy years of its completion, although there are records of inhabitation and some remains and pottery shards for subsequent years. Chinese porcelain shards have been found from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, coins from the fourteenth. Yet no more temples were built in central Java after the beginning of the tenth century. It was not until the thirteenth century that a revival of stone construction began, taking place several hundred miles to the east of Borobudur. Did an an ominous volcanic eruption (the sun became obscured, enveloped in a fog are Raffles words on an eruption that took place during his tenure, much later) obscure Borobudur or did the energy of trade and commerce move to coastal areas? Certainly the arrival of Islam in the fifteenth century challenged any remnants of Buddhist practice in the archipelago. Was there a sense of the stupa being built for the future to reclaim? This might be a more tantric idea: that an embryonic process goes on into the future, having a salutary effect on the citizens and the environment. And that these monuments are built with the enlightenment of future generations in mind. Certainly the current world situation would seem to belie this, given the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas by the Taliban in recent years and the tragic conflation of religious conflicts due to political, economic, and ideological power struggles.