Table of Contents

IDEAS EXPLAINED

Hans-Georg Moeller, Daoism Explained:

From the Dream of the Butterfly to the Fishnet Allegory

Joan Weiner, Frege Explained:

From Arithmetic to Analytic Philosophy

Hans-Georg Moeller, Luhmann Explained:

From Souls to Systems

Graham Harman, Heidegger Explained:

From Phenomenon to Thing

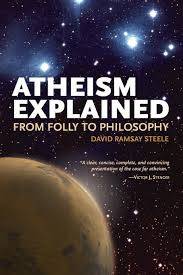

David Ramsay Steele, Atheism Explained:

From Folly to Philosophy

IN PREPARATION

David Detmer, Sartre Explained

Rondo Keele, Ockham Explained

Paul Voice, Rawls Explained

David Detmer, Phenomenology Explained

Rohit Dalvi, Deleuze and Guattari Explained

To David McDonagh

Honesty is an achievement.

Preface

There are many books explaining atheism and arguing for it. Most of them fall into one of two types. The first type takes for granted a lot of technical language in philosophy of religion and soon loses the ordinary reader. The second type is usually personal in tone, seething with moral indignation against atrocities committed in the name of God, unsystematic in approach, and occasionally betraying ignorance of just what theists have believed.

Several books of both types are really excellent in their way, but Im trying something different. I explain atheism by giving an outline of the strongest arguments for and against the existence of God. My aim is to provide an accurate account of these arguments, on both sides, in plain English.

Following a Christian upbringing, I became an atheist by the age of thirteen. For a few years, it seemed axiomatic that I ought to do my bit to help convert the world to atheism. Then I became more interested in social and political questions.

Over the years since then, the whole issue of atheism gradually sank into comparative insignificance. It seemed clear to me, and still seems obvious today, that there is no God. But it has also gradually become apparent that this issue has less practical urgency than I used to imagine.

Most people who say that they believe in God live their lives pretty much as they would if they did not believe in God. They are nominal theists with secular outlooks and secular lifestyles. They would judge it to be at best a lapse of taste if any mention of God were to intrude into their everyday lives.

Whether or not a person believes in the existence of God seems to have no bearing on what that person thinks about war, globalization, welfare reform, or global warming (there are of course statistical correlations, but these seem to be due to mere fashion, not to any logical necessity). The social and political positions taken up by Christian churches, for example, are merely a reflection of ideological currents generated in the secular world. The landmark papal encyclicals on social questions, of 1891 and 1931, tried to steer a middle course between socialism and free-market capitalismjust one illustration of the fact that, since the eighteenth century, secular social movements have made the ideological running; the churches flail about trying to come up with some angle on social questions that they can represent as distinctively religious.

Its true that believers in God are usually gratified to discover that the Almighty sees eye to eye with them on many practical issues, but theists can be found on all sides of any policy question. There is no distinctively theist view or Christian view on anything of practical importance. Still less does belief or disbelief in God have any relevance to whether a person is considerate, courageous, kind, loving, tolerant, creative, responsible, or trustworthy.

In recent years I have spent a good portion of my energies on combating the ideas of two atheists: Karl Marx and Sigmund Freud. This bears out my view that atheism is purely negative, like not believing in mermaids, and is in no way a creed to live by or anything so grandiose. I view belief in God as like belief in the class struggle or belief in repressed memoriesjust a mistake. The issue of theism or atheism is something to get out of the way early, so that you can focus your attention on matters more difficult to decide and more important.

Today my view of atheism is very different from what it was in my teens. Then I thought that the existence of God was a vitally urgent question. Now, I still believe theres no God, but I do not think this is as consequential a matter as I used to suppose. I am struck by three considerations.

First, the existence of God seems preposterous, but so do some of the things quantum physics tells me, and I do accept quantum physics. (I do not accept quantum physics because it seems preposterous, but because it tests out well; its predictions are borne out by numerous experiments.) While this does not make me directly more disposed to believe in God, it does make me more acutely aware of how complicated the world is and how little I know about it. And this makes me entertain the possibility of some future shifts in human knowledge that might conceivably make some kind of Gods existence a more promising hypothesis than it seems to be right now. (I say some kind of God because, as youll see if you keep reading, God as strictly defined by Christianity and Islam is an incoherent notion which can be demonstrated not to correspond to anything in reality.)

Second, I have come to recognize something that was once unclear to me: that the bare existence of a God, if we accepted it, would not take us even ten percent of the way toward accepting the essentials of any traditional theistic system. For example, every human would have to possess an immortal soulsomething that might be true if there were no God, and might be false if there were a God. God would have to decree a major difference to peoples lot in the afterlife according to whether those people believed in his existence in this life. And usually, some uneven collection of ancient documents, such as the Tanakh, the New Testament, or the Quran, would have to be accorded a respect out of all proportion to its literary or philosophical merit. Even if we were to accept the bare existence of God, these additional elementary portions of traditional theistic religion would remain as fantastically incredible as ever. If I were to become convinced tomorrow of the existence of God, I would be no more inclined to become a Christian or a Muslim than I am now.

Third, so many horrible deeds have been done by Christians and Muslims in the name of their religions that a young Christian or Muslim who becomes an atheist often tends to assume that there is some inherent connection between adherence to theism and the proclivity to commit atrocities. The history of the past one hundred years shows us that atheistic ideologies can sanctify more and bigger atrocities than Christianity or Islam ever did. The casualties inflicted by Communism and National Socialism vastly exceedmany hundredfoldthe casualties inflicted by theocracies. In some cases (Mexico in the 1930s, Soviet Russia, and the Peoples Republic of China), there has been appalling persecution of theistic belief by politically empowered atheists, exceeding any historical atrocities against unbelievers and heretics.