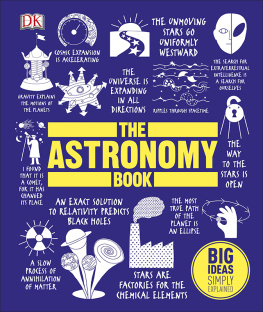

Throughout history, the aim of astronomy has been to make sense of the Universe. In the ancient world, astronomers puzzled over how and why the planets moved against the backdrop of the starry sky, the meaning of the mysterious apparition of comets, and the seeming remoteness of the Sun and stars. Today, the emphasis has changed to new questions concerning how the Universe began, what it is made of, and how it has changed. The way in which its constituents, such as galaxies, stars, and planets, fit into the larger picture and whether there is life beyond Earth are some of the questions humans still endeavour to answer.

Understanding astronomy

The baffling cosmic questions of the day have always inspired big ideas to answer them. They have stimulated curious and creative minds for millennia, resulting in pioneering advances in philosophy, mathematics, technology, and observation techniques. Just when one fresh breakthrough seems to explain gravitational waves, another discovery throws up a new conundrum. For all we have learned about the Universes familiar constituents, as seen through telescopes and detectors of various kinds, one of our biggest discoveries is what we do not understand at all: more than 95 per cent of the substance of the Universe is in the form of dark matter and dark energy.

The origins of astronomy

In many of the worlds most populated areas today, many of us are barely aware of the night sky. We cannot see it because the blaze of artificial lighting overwhelms the faint and delicate light of the stars. Light pollution on this scale has exploded since the mid-20th century. In past times, the starry patterns of the sky, the phases of the Moon, and the meanderings of the planets were a familiar part of daily experience and a perpetual source of wonder.

Few people fail to be moved the first time they experience a clear sky on a truly dark night, in which the magnificent sweep of the Milky Way arches across the sky. Our ancestors were driven by a mixture of curiosity and awe in their search for order and meaning in the great vault of the sky above their heads. The mystery and grandeur of the heavens were explained by the spiritual and divine. At the same time, however, the orderliness and predictability of repetitive cycles had vital practical applications in marking the passage of time.

Archaeology provides abundant evidence that, even in prehistoric times, astronomical phenomena were a cultural resource for societies around the world. Where there is no written record, we can only speculate as to the knowledge and beliefs early societies held. The oldest astronomical records to survive in written form come from Mesopotamia, the region that was between and around the valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, in present-day Iraq and neighbouring countries. Clay tablets inscribed with astronomical information date back to about 1600 BCE. Some of the constellations (groupings of stars) we know today have come from Mesopotamian mythology going back even earlier, to before 2000 BCE.

"Philosophy is written in this grand book, the Universe, which stands continually open to our gaze."

Galileo Galilei

Astronomy and astrology

The Babylonians of Mesopotamia were greatly concerned with divination. To them, planets were manifestations of the gods. The mysterious comings and goings of the planets and unusual happenings in the sky were omens from the gods. The Babylonians interpreted them by relating them to past experience. To their way of thinking, detailed records over long periods were essential to establish connections between the celestial and the terrestrial, and the practice of interpreting horoscopes began in the 6th century BCE. Charts showed where the Sun, Moon, and planets appeared against the backdrop of the zodiac at some critical time, such as a persons birth.

For some 2,000 years, there was little distinction between astrology, which used the relative positions of celestial bodies to track the course of human lives and history, and the astronomy on which it relied. The needs of astrology, rather than pure curiosity, justified observation of the heavens. From the mid-17th century onwards, however, astronomy as a scientific activity diverged from traditional astrology. Today, astronomers reject astrology, because it is unfounded in scientific evidence, but they have good reason to be grateful to the astrologers of the past for leaving an invaluable historical record.

Time and tide

The systematic astronomical observations once used for astrology started to become increasingly important as a means of both timekeeping and navigation. Countries had highly practical reasons civil, as well as military to establish national observatories, as the world industrialized and international trade grew. For many centuries, only astronomers had the skills and equipment to preside over the worlds timekeeping. This remained the case until the development of atomic clocks in the mid-20th century.

Human society regulates itself around three natural astronomical clocks: Earths rotation, detectable by the apparent daily march of the stars around the celestial sphere to give us the day; the time our planet takes to make a circuit around the Sun, otherwise known as a year; and the monthly cycle of the Moons phases. The combined motion in space of Earth, the Sun, and the Moon also determines the timing and magnitudes of the oceanic tides, which are of crucial importance to coastal communities and seafarers.

Astronomy played an equally important role in navigation, the stars acting as a framework of reference points visible from anywhere at sea (cloud permitting). In 1675, British King Charles II commissioned an observatory, the Royal Observatory at Greenwich, near London. The instruction to its director, the first Astronomer Royal, John Flamsteed, was to apply himself diligently to making the observations needed for the perfecting of the art of navigation. Astronomy was largely discarded as the foundation of navigation in the 1970s, and replaced by artificial satellites, which created a global positioning system.