Sounds Appealing

David Crystal is Honorary Professor of Linguistics at the University of Wales, Bangor. His many books range from clinical linguistics to the liturgy and Shakespeare. He is the author of The Story of English in 100 Words, Spell It Out: The Singular History of English Spelling, and Making a Point: The Pernickety History of English Punctuation, all published by Profile. His Stories of English is a Penguin Classic.

By David Crystal in this series

The Story of English in 100 Words

Spell It Out: the Singular Story of English Spelling

Making a Point: the Pernickety Story of English Punctuation

Making Sense: The Glamorous Story of English Grammar

Also by David Crystal

The Gift of the Gab: How Eloquence Works

The Oxford Dictionary of Original Shakespearean Pronunciation

Wordsmiths and Warriors: the English-language Tourists Guide to Britain

Evolving English: One Language, Many Voices

The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language

By Ben and David Crystal

Oxford Illustrated Shakespeare

Shakespeares Words: a Glossary and Language Companion

Sounds Appealing:

The Passionate Story of English Pronunciation

David Crystal

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

3 Holford Yard

Bevin Way

London WC1X 9HD

www.profilebooks.com

Copyright David Crystal, 2018

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

All reasonable efforts have been made to obtain copyright permissions where required. Acknowledgements appear on . Any omissions and errors of attribution are unintentional and will, if notified in writing to the publisher, be corrected in future printings.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

eISBN 978 1 78283 234 8

Contents

Introduction

In the 1980s, I found myself as the voice of language on BBC Radio 4. It was a time when the range of presenters you would hear on the air in Britain had greatly increased, following the emergence of local radio stations all over the country, and with new voices came new usages and new accents. Many listeners, used to the traditional voice of the BBC, with its echoes of wartime authority and pride, were taken aback, and sent letters and postcards in large numbers, expressing concern at what they perceived to be a falling of standards. The comments related to all aspects of spoken language, including vocabulary and grammar, but most were passionate about pronunciation.

The BBC didnt know what to do with the huge postbags that were coming in. There was a Pronunciation Unit that dealt with queries (such as how to pronounce the name of a foreign place or politician), but the range of issues being raised went well beyond its remit, and the small team that staffed it couldnt cope with the quantity. So, as a known linguist whod already done some broadcasting, it sent them to me.

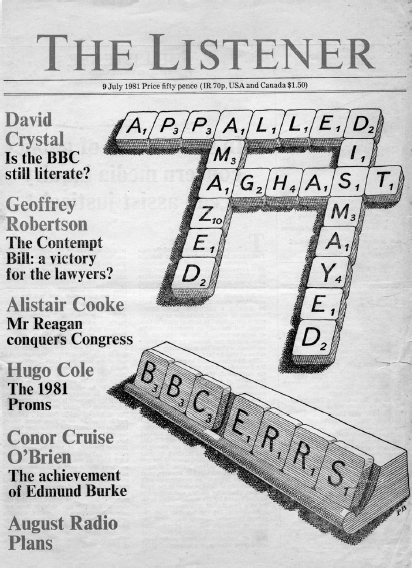

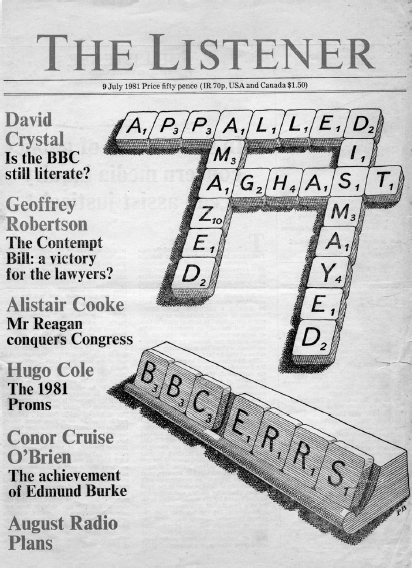

I went through a months worth, and wrote what I thought was going to be a single programme about the kind of points being made. It was called How dare you talk to me like that, and it was printed in The Listener magazine on 9 July 1981. The editor gave it a new and provocative title: Language on ). I was told that it got the largest response of the month. They reprinted it six months later, when the programme was repeated. Another huge response.

For my script, I decided to organize the complaints into a top twenty list. (There were only ever complaints. In the hundreds of letters and cards that I read, nobody once wrote words of praise.) Several were to do with pronunciation the placing of stress in long words ( con troversy or con trov ersy), the sounding of foreign words (such as restaurant), regional variations (in words like poor), the omission of vowels or consonants (as when February becomes Febry), the insertion of r when it isnt in the spelling (as when drawing becomes draw-ring), and the dropping of final consonants (as in las year).

What really struck me was the intemperate language used by the complainers, and The Listener printed some of their emotive adjectives on its cover. People didnt just say they disliked a pronunciation. They used the most extreme words they could think of. They were appalled, aghast, horrified, outraged, distressed, dumbfounded when they heard something they didnt like. Appalled was the commonest usage. While I was writing my script, in May 1981, news came through that there had been an assassination attempt in Rome on Pope John Paul II. So I ended my piece with a wry comment: if one can be appalled about errors in pronunciation, what kind of language is there left to refer to ones feelings when great men get shot?

Somebody at the BBC noticed the furore, and asked me to do a series offering an outlet, as it were, for all this pent-up passion. It was called Speak Out. Just three episodes. Not enough. The letter rate increased. Another series followed, English Now, and this ran for nearly a decade. There was no let-up. After some episodes, I would get as many as a thousand items through the post. Pronunciation was always the main talking point. And heres the interesting thing: the vast majority would have a first-class stamp. Writers evidently felt a sense of urgency. Whatever the point being complained about was, it needed to reach the BBC by tomorrow.

My own pronunciation didnt escape the ire of some listeners. One letter, addressed to the director-general of the BBC, copied to me (thus, two first-class stamps), asked for my immediate removal as presenter on the grounds that programmes to do with pronunciation shouldnt be given to someone who says the word one to rhyme with on rather than with sun. I dont know whether the DG replied, but I did, indirectly, by using the letter in one of the programmes as an excellent illustration of the microscopic way that some listeners actually listen.

What is it about pronunciation that produces such a response? Why does pronunciation get to people in a way that other aspects of speech dont? Why are we so passionate about it? Has it always been that way? Will it always be that way? Is it the same all around the English-speaking world, or is it just a British thing? These are the kinds of questions that this book will explore. The why questions first.

A poetic voice

Ogden Nash cleverly versified his complaints in Ill Hush If Youll Hush, published as one of the poems of indignation in The Primrose Path (1936).

Sweet voices have been presented by Nature

To creatures of varying nomenclature

The bird, when he unlocks his beak,

Emits a melody unique;

The lions roar, the moo-cows bellow,

Are clearly pitched and roundly mellow;

The squirrels chatter, the donkeys bray,

Next page