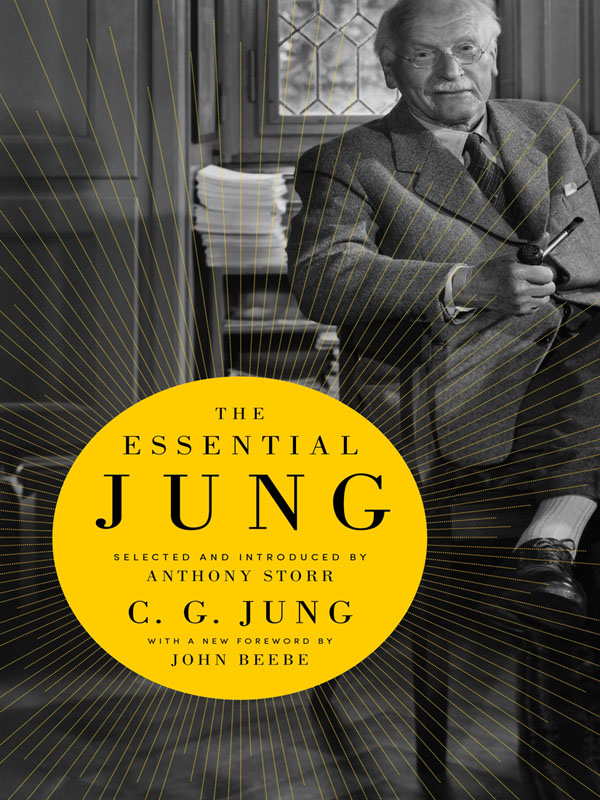

The Essential Jung

Selected and introduced

by Anthony Storr

With a new foreword by John Beebe

Princeton University Press

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 1983 by Princeton University Press

Copyright in the introductory matter Anthony Storr 1983

Foreword to the 2013 edition copyright 2013 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Selected from The Collected Works of C. G. Jung (translated by

R.F.C. Hull), The Freud/Jung Letters (passage translated by

R.F.C. Hull), C. G. Jung: Letters, and C. G. Jung:Word and Image, all

published by Princeton University Press; and from Memories,

Dreams, Reflections by C. G. Jung (translated by Richard and Clara

Winston), copyright 1961, 1962, 1963 by Random House, Inc.,

and published by Pantheon Books, NewYork.

Paperback reissue, with a new foreword by John Beebe, 2013

Library of Congress Control Number 2013934212

ISBN 978-0-691-15900-3

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Foreword to the 2013 edition

The Essential Jung provides a concise, beautifully paced compilation of some of Jungs most pithy passages. It benefits from the touch of its original editor, the late English psychiatrist Anthony Storr, an eclectic aficionado of Jungian thought who knew how to let the master speak for himself. Time has not altered the wisdom of his choices: it is good to have them at hand again now.

Yet when The Essential Jung first came out, its title put me off. As a reader of analytical psychology who had come of age in the midst of a Jung boom, I doubted that a volume of this modest size, ushering its readers swiftly through the different rooms of the mansion that had become Jungs published writings, could disclose an essential Jung.

What becomes clear as one peruses the book anew is how rightly called it is, for its pages repeatedly reveal how much Jung was himself the essentialist, ever seeking to pare the points he wanted to make about the nature of the psyche. Writing in a time when the philosophic basis for essentialism was rapidly going out of fashion, Jung revived the tradition of summary judgment as a path to insight. Though in the philosophic tradition of Lao-Tzu and Lucretius, he seemed to be walking in from the country of natural philosophy, the standpoint he conveyed in his own voice had the urbane ring of Lichtenberg and Voltaire.

By fitting together different jewels from an oeuvre that was forever polishing its facets, Storr has succeeded in creating a lapidary mirror of Jungs own process as a psychological writer. He leads us to reflect that Jung not only argued for a self that both centers and surrounds our psychic lives but showed how living in such a self can deliver the gift of meaning. When Jung, with the magical verbal flight path of a literate hawk, manages to encompass, in a few arresting paragraphs, every home truth he has ever delved into, we find not only what is basic for analytical psychologists, but a ground for the rest of us. I suspect a new generation of readers will be able to find in Storrs sturdy survey everything they need to achieve a fresh estimation of Jungs work. They should not be surprised if it also delivers to them the energy required to pursue that quintessential oeuvre further.

Note on the Text

Bibliographical details of the works from which I have taken extracts Collected Works (CW), Memories, Dreams, Reflections (MDR), Septem Sermones ad Mortuos, The Freud/Jung Letters and Letters are given on pages 4345. English and American page or paragraph numbering diverges only in the case of MDR; when quoting from this book I have given the English hardback editions pages followed by those of the American edition.

I have been selective about my inclusion of footnotes, keeping those of Jungs which illuminate the text or which refer to sources of interest to the non-specialist reader, but omitting his and his editors references to works which, particularly in the case of the alchemical volumes, are unobtainable by all but the most dedicated scholars. Where editors notes have been retained, they are within square brackets. I have used the bibliographies contained in CW to fill out Jungs footnotes where appropriate.

Preface

Throughout his long life, C. G. Jung was a prolific writer, so that his Collected Works run to no less than eighteen large volumes. In addition, there are five volumes of his seminars, with one more to comethe Zofingia Lectureswhich he gave when he was a medical student; two volumes of his letters; a separate volume of his correspondence with Freud; and his autobiography, Memories, Dreams, Reflections. Comparatively few people are prepared to read the whole corpus of this material, but many might welcome the opportunity to become acquainted with Jungs thought as he himself expounded it. This book is an attempt to distil the essential features of Jungs psychology as it developed during the course of his life by means of extracts from his own writings. Since Jungs way of thinking may be unfamiliar to contemporary readers, I have summarized the main features of his thought in an introduction, and I have prefaced the extracts which I have chosen with brief explanatory remarks. But, so far as is possible, I have let Jung present his ideas in his own words. My purpose has been exposition, not criticism, and it must not be assumed that I personally subscribe to everything that Jung wrote.

Anthony Storr

Introduction

Carl Gustav Jung was born on 26 July 1875 and died on 6 June 1961. The greater part of his early childhood was spent at Klein-Hningen, near Basel, to which his family moved in 1879. Jung attended the local school from the age of six, and, in his eleventh year, was transferred to the Gymnasium in Basel. From here, he went on to study medicine at the University of Basel during the years 18951900. Concurrently, he read extensively in the fields of philosophy and theology.

In 1900, he moved to Zurich where he became an assistant physician to Eugen Bleuler at the Burghlzli mental hospital. He was later promoted to Senior Staff Physician. In 19023, he spent a term at the Salptrire in Paris in order to study psychopathology with Pierre Janet. During these first years in psychiatry, he wrote his MD dissertation, On the Psychology and Pathology of So-called Occult Phenomena; undertook experimental work in word association; and, in 1903, married Emma Rauschenbach, by whom he had a son and four daughters. In 1905, he was appointed a lecturer in the University of Zurich.

In 1907, Jung published a pioneering book on schizophrenia, The Psychology of Dementia Praecox, which he sent to Freud. This led to a meeting between the two men in Vienna, and to a close association between them which lasted until 1913. In 1909, Jung, in company with Freud and Ferenczi, paid his first visit to the USA, where he lectured on word-association experiments and received an honorary degree from Clark University, in Massachusetts. In the same year, Jung gave up his post at the Burghlzli in favour of his growing private practice which he conducted in his own house at Ksnacht on the Lake of Zurich. Although he travelled in various parts of the world and paid frequent visits to his country retreat in Bollingen, which was also on the Lake of Zurich, Jung continued to practise and to write in the same house in Ksnacht until his death in 1961. His last piece of writing was completed only ten days before he died.

Next page