Table of Contents

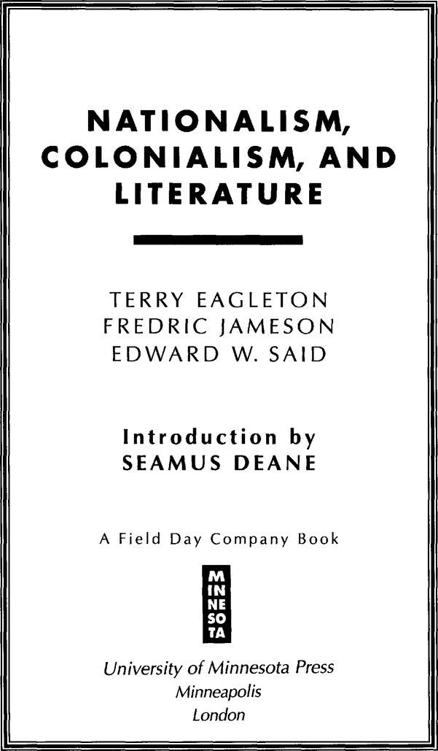

This collection copyright 1990 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota

Introduction copyright 1990 by Seamus Deane.

Nationalism: Irony and Commitment copyright 1988 by Terry

Eagleton. Modernism and Imperialism copyright 1988 by Fredric

Jameson. Yeats and Decolonization copyright 1988 by Edward W. Said.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published by the University of Minnesota Press

111 Third Avenue South, Suite 290, Minneapolis, MN 55401-2520

http://www.upress.umn.edu

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

Fifth printing 2001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Nationalism, colonialism, and literature / Terry Eagleton, Fredric

Jameson, and Edward W. Said ; introduction by Seamus Deane.

p. cm.

These essays were originally published as pamphlets by Field

Day Theatre CompanyPref.

Contents: Nationalismirony and commitment/Terry Eagteton

Modernism and imperialism / Fredric JamesonYeats and

decolonization / Edward W. Said.

ISBN 978-1-452-91657-6.ISBN 0-8166-1863-1 (pbk.)

1. English literatureIrish authorsHistory and criticism.

2. Yeats, W. B. (William Butler), 18651939Criticism and interpretation. 3. Joyce, James, 18821941Criticism and interpretation. 4. Nationalism in literature. 5. Colonies in literature. 6. Ireland in literature. 7. NationalismIreland.

I. Eagleton, Terry, 1943Nationalismirony and commitment.

1990. II. Jameson, Fredric. Modernization and imperialism. 1990.

III. Said, Edward W. Yeats and decolonization. 1990. IV Field

Day Theatre Company.

PR8753.N38 1990

820-9358dc20 90-10855

The University of Minnesota

is an equal-opportunity

educator and employer.

INTRODUCTION

SEAMU S DEANE

T he three essays presented here have in common with one another and with the Field Day enterprise the conviction that we need a new discourse for a new relationship between our idea of the human subject and our idea of human communities. What is now happening in Ireland, most especially in Northern Ireland (constitutionally an integral part of the United Kingdom), is only one of the many crises that have made the need for such a discourse peremptory. In Africa, South America, the Middle East, the Soviet Union, and Eastern Europe, the nature of the crisis is more glaringly exposed and its consequences seem both more ominous and far-reaching in their effects. Nevertheless, the Irish-English collision has its own importance. Ireland is the only Western European country that has had both an early and a late colonial experience. Out of that, Ireland produced, in the first three decades of this century, a remarkable literature in which the attempt to overcome and replace the colonial experience by something other, something that would be native and yet not provincial, was a dynamic and central energy. The ultimate failure of that attempt to imagine a truly liberating cultural alternative is as well known as the brilliance of the initial effort. Now that the established system has again been called into question, even to the point where it must seriously alter or collapse, Irish writing, operating in the shadow or in the wake of the earlier attempt, has once more raised the question of how the individual subject can be envisaged in relation to its community, its past history, and a possible future.

Terry Eagletons analysis of nationalism identifies the radical contradictions that necessarily beset it. The oppositional terms it deploys are the very terms it must ultimately abolish. Yet such abolition is not an easy, peremptory gesture. The divisions of English and Irish, Protestant and Catholic, must be lived through in the present. It is, therefore, necessary to sustain commitment to them under the aegis of irony. Otherwise the oppressive conditions they bespeak will merely be reproduced. In Europe the category of the aesthetic has as its project the reconciliation of the specific and the universal. This has no application in Ireland, where the radical and abstract Enlightenment view of the individual and the regionalist particularity of nineteenth-century Irish nationalism remain discrete, with no totalizing vision that can contain or conciliate them. This is true even when we consider Joyces writings where the totalizing process finally homogenizes difference, erases rather than lives through oppositions like those of the cosmopolitan versus the national community. Any politics that has a transformative power has to envisage, if in a negative way, the freedom and self-autonomy that would make such politics unnecessary. This is not merely a theoretical paradox. It is a condition that has to be passionately lived.

Fredric Jamesons essay pursues the contradiction, explored in his other works, between the limited experience of the individual and the dispersed conditions that govern it. In any imperial system, the subject, living in the home country, does not have any living access to the far-flung system that makes his or her subjective existence possible. Jameson argues that the attempt to achieve some coordination between private existence and the global, institutional apparatus of imperialism has been the stimulus behind many of the experimental forms assumed by modern literature. Joyces experiments in representation and his dismantling of its traditional forms and assumptions are, for Jameson, a particularly telling example of the way in which a closed society, like Dublin, still available to the individual consciousness as an autonomous culture, has had to envisage its relationship with a metropolitan and imperial center like London as a paralyzed, even catatonic condition. It has no motor force of its own. It is subject to agencies beyond its control and therefore imperfectly known or realizedthe British and Roman Catholic imperial world systems. Reading Joyce against an English writer like Forster, Jameson discloses the reasons for Joyces disintegration of the monadic subject of the bourgeois novel. Forsters failure to do so is not merely a formal failure; it bespeaks the failure of the political creed of liberalism, with its peculiarly intense valorization of the autonomous human subject and its consequent failure either to apprehend or to comprehend the operations of the system that initially gave birth to it and that ultimately undermines it.

Edward Said concentrates on Yeats, seeing his work as an exemplary and early instance of the process of decolonization, the liberation of the poets community from its inbred and oppressive servility to a new, potentially revolutionary condition. The Yeats that other colonial countries experience is not necessarily the Yeats Ireland experiences now. For, although he did perhaps fall in the end into a blind provincialism, his attempt to escape from the thrall of Irelands mutilating nineteenth-century experience has been reproduced and developed in other countries and cultures since. The asphyxiating aspects of a regional nativism, although they persist in his work and become more pronounced in its later phases, do not obliterate its radically liberating elements. These have been imitated and transcended in the writings of African, Palestinian, and South American writers who have read Yeats as a poet whose re-creation of himself and his community provides a model for their own projectsthe giving of a voice and a history to those who have been deprived of the consciousness of both.