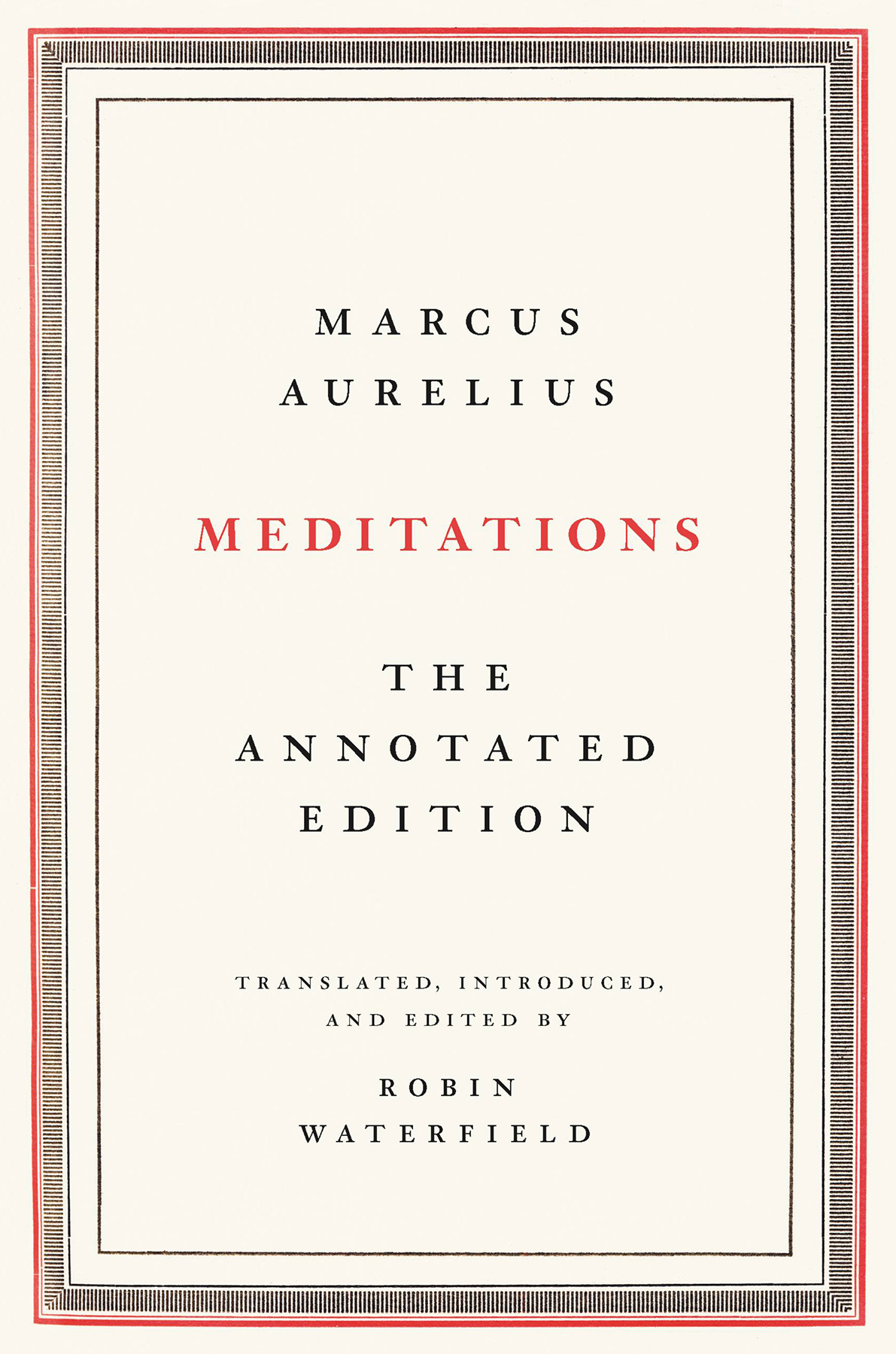

Copyright 2021 by Robin Waterfield

Cover design by Ann Kirchner

Cover image duncan1890 via Getty Images

Cover copyright 2021 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright.

The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Basic Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.basicbooks.com

First Edition: April 2021

Published by Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Basic Books name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Marcus Aurelius, Emperor of Rome, 121180, author. | Waterfield, Robin, 1952translator.

Title: Meditations / Marcus Aurelius; translated, introduced and edited by Robin Waterfield.

Other titles: Meditations. English

Description: Annotated edition. | New York: Basic Books, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020046877 | ISBN 9781541673854 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781541675605(ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Ethics. | Stoics. | Life.

Classification: LCC B580 .H3 M3713 2021 | DDC 188dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020046877

ISBNs: 978-1-5416-7385-4 (hardcover), 978-1-5416-7560-5 (ebook)

E3-20210226-JV-NF-ORI

FOR JULIAN AND KATHERINE

Marcus Aureliuss Meditations is high on the list of the most famous and widely read works of philosophy in the world. It has often been translated into English, but the Greek in which Marcus wrote is frequently so difficult that there is always room for another version. The justification of this book, however, is not just an improved translation but an increased degree of annotation. The intention of the Introduction and the notes is that they should deepen anyones understanding of Marcuss work while falling short of hardcore philosophical commentary. The Introduction covers general issues that illuminate the book as a whole, and I wrote notes wherever I felt that Marcuss meaning would not be immediately clear to at least some readers. So the notes serve, as it were, the short-term function of explaining passages as they are read, whereas the Introduction has a more general purpose.

Stoicism, an ancient philosophical system, has been rediscovered in recent years, and many thousands of people around the world consider themselves Stoics and try to put it into practice. My acquaintance with this Modern Stoicism is minimal, and I have deliberately kept it so because I want to try to understand Marcus on his own terms and in his own day. But Meditations is a core text for Modern Stoics, and in a sense they are exactly the kind of reader for whom the book is intended.

I would like to thank James Romm for launching me on this project, and, at Basic Books, Dan Gerstle for commissioning the book, Claire Potter for seeing it through, and Alex Colston and Christina Palaia for their thorough and very helpful editorial work. David Fideler (stoicinsights.com) was supportive in various ways, not least by sharing some of his knowledge of Seneca with me. John Sellars graciously sent me a prepublication copy of his Marcus Aurelius. Above all I am grateful to friends new and old: my wife, Kathryn, was as usual my first reader, and then Brad Inwood and John Sellars, two of the worlds leading interpreters of Stoicism, commented on the finished typescript. I took note of all their suggestions for improvement.

The famous Aurelian Column, a hundred feet high and still standing in Rome, was erected not long after the death of Marcus Aurelius to commemorate his military victories on the Danube in the early 170s. A frieze of relief sculptures spirals up its outer face, divisible into 116 scenes that reflect the chronological order of the so-called Marcomannic Wars the Romans fought against a number of Germanic peoples, including the Marcomanni. Marcus can be seen in about half of the scenes. Two sections depict famous miracles. On one occasion, a heavy downpour of rain confounded the enemy, while a battalion of surrounded Roman soldiers was refreshed and able to escape; on another, a Roman fortress was under siege, but the soldiers were saved when lightning destroyed one of the enemys siege engines.

Many sections of the frieze are taken up with gruesome scenes, not just of murderous battles but of actions that would today be classified as war crimes: prisoners being decapitated,

Yet the Marcus of Meditations is regarded as a man of peace, a thoughtful philosopher offering sage advice for daily living and self-improvement. The moral to be drawn from this contrast is the one Marcus frequently stresses in his writing: everyone, even or especially an emperor, has to play the hand he has been dealt. As his friend and teacher Marcus Cornelius Fronto warned him early in his reign: Even if you succeed in attaining the wisdom of Cleanthes or Zeno, yet against your will you must put on the purple cloak, not the philosophers tunic of coarse wool. And the emperors purple cloak often had to be exchanged for armor. Marcus might have preferred to be a private individual with time for reading and making progress on the Stoic path rather than an emperor, but as a Stoic, he had to accept and make the best use of the lot that fate had handed him.

Marcus is famous for the conjunction of imperial power and philosophy and has even been called a philosopher-king, the kind of enlightened ruler that Plato famously held out as He was by far the wealthiest and most powerful man in the world, but self-discipline and philosophy kept him from abusing his position.

Meditations reveals a man who longed to do good and to love all humanity, while the Aurelian Column shows how his status as emperor impeded his attainment of these goals. Hence, at the beginning of entry 10.9 Marcus seems to acknowledge that war was an impediment to the realization of his less worldly hopes. By the same token, the tone of Meditations is that of an aspirant, someone who urgently wants to do better and to live as a philosopher, but who is constantly thwarted by events and by his own weakness. But this is why Meditations is still so widely read, because no one is perfect and we recognize ourselves in Marcuss flaws and aspirations.

MARCUSS ROUTE TO THE IMPERIAL THRONE

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, emperor of Rome from March 7, 161, until his death on March 17, 180, was born Marcus Annius Verus in Rome on April 26, 121, during the reign of the emperor Hadrian.philosophy. Some of the correspondence between him and one of his teachers of rhetoric, Fronto, has survived, and the letters show Marcus to have been an intense, open-hearted, bookish young man. Rhetoric was an inevitable topic of study for someone destined for public life, but philosophy was his personal choice, and he was attracted to it from an early age (1.6).