First published in Great Britain in 2013 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Timothy Venning 2013

ISBN: 978-1-78159-125-3

PDF ISBN: 978-1-78346-428-9

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-78346-894-2

PRC ISBN: 978-1-78346-661-0

The right of Timothy Venning to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in 11pt Ehrhardt by

Mac Style, Beverley, E. Yorkshire

Printed and bound in the UK by MPG

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Pen & Sword Discovery, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe True Crime, Wharncliffe Transport, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics, Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Introduction

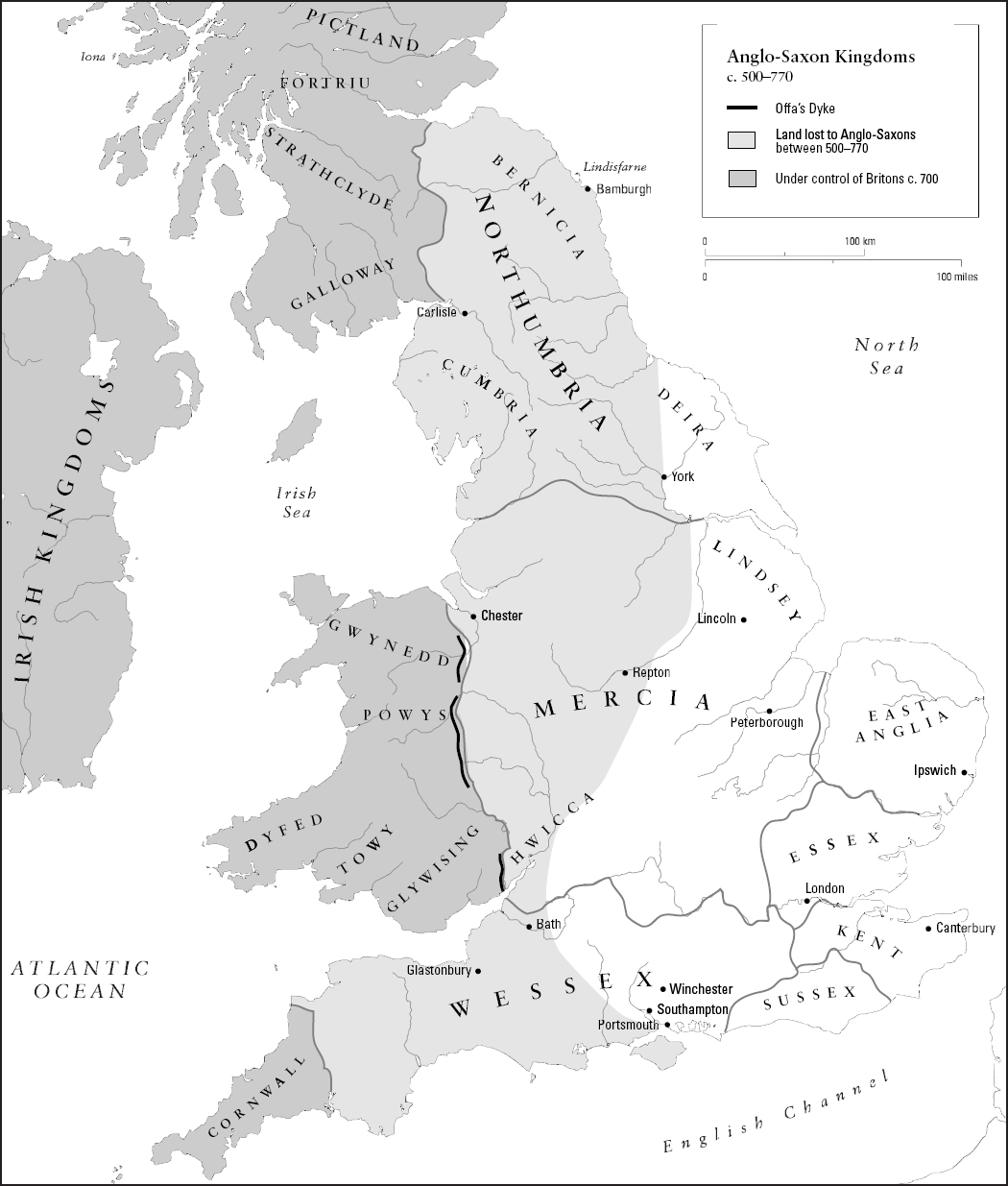

O ne of the few dates from medieval British history still firmly in the popular memory is 1066. The end of Anglo-Saxon England and the Norman Conquest are still viewed as major events Englands forcible first entry into Europe. Its somewhat isolated socio-political structure was integrated into the world of Western European Latin-speaking Christendom and what is loosely described as feudalism. The victor, Duke William of Normandy (known, though not to his face, as The Bastard rather than the later sobriquet The Conqueror), had no serious claim on the throne, though he did his best to claim that the late King Edward (not known then as The Confessor) had named him as heir and the intervening king, Harold Godwinson, was an oath-breaking usurper. The kings after the Conquest numbered themselves as from 1066, not from English unification in the 920s Edward I (r. 12721307) was in fact the fourth Edward to rule England, starting with the national unifier Edward the Elder (r. 899924). The work of the unification of England took place with the northwards expansion of the allied kingdoms of Edwards Wessex and his sister Aethelfledas Mercia into the Danelaw (East Midlands and East Anglia), settled by Danish incomers in the 870s, in 91118, and by 924 Edward was recognized as overlord by the Danish kingdom of York and the Norse settlers in Lancashire. He secured Mercia too on his sisters death in 918, and York was incorporated into England in 927 though it subsequently revolted and was not finally annexed until 954. Cumbria, independent but linked to Strathclyde in Scotland, was partly overrun in 945 but modern Cumberland only appears to have been annexed in 1092; the shifting Anglo-Scottish border in the east moved south from the Forth to its present position in the 970s.

The creation of a kingdom of England was thus far from straightforward, and there was no tradition of a united Anglo-Saxon kingdom of England so Mercian and Northumbrian regional separatism remained an issue. Edwards annexation of Mercia in 918 was immensely aided by the fact that its heir, his niece Egwynn, was a girl who could not lead armies and there was no male candidate available. Even so, his eldest son, Athelstan, brought up in Mercia and the offspring of a legally questionable marriage, was passed over for Wessex and seems to have been intended to rule Mercia; he only secured Wessex when his half-brother Aelfweard died weeks after Edward in 924. The fact that he was not crowned for a year implies serious resistance to this. Had Aelfweard not died, would England have remained united? Similarly, it is possible that Athelstans half-brother and successor Edmund intended both his sons, Edwy and Edgar, to rule a kingdom each when they were adult; Edwy succeeded to both in 955 but in 957 Mercia and Northumbria revolted in Edgars favour. Edwys death in 959 saw unity restored, but was this inevitable? The succession to Edgar in 975 was disputed between partisans of his two under-age sons, Edward and Aethelred, though division was avoided and in 978 Edward was murdered.

In the 1000s England was gradually overrun by a Viking army under Swein Forkbeard, king of Denmark, a war that could have seen England split into two again with him ruling the Danelaw and Northumbria, which were first to accept him. As Wessex rallied against the Danes under Aethelreds son Edmund Ironside in 1016 the latters defeat at Ashingdon saw England divided between him and Sweins son Cnut, though this was probably only a truce born of exhaustion and Edmund quickly died. A temporary division between the partisans of Cnuts two sons, Harold Harefoot and Harthacnut, followed Cnuts death in 1035, though that was soon reversed as first one then the other took control; and in 1066 King Harald Hardradi of Norway endeavoured to add York (and perhaps more) to his wide-flung domains. After Harald was killed by Harold Godwinson the latter fell in battle against Duke William within weeks but a less decisive result could have left England divided again, as in 1016.

The triumph of one state in England was far from certain throughout this period, and was due to genetic and military luck rather than inevitability. The What Ifs of English unification are thus many, and pose possibilities of a future for England radically different from reality. And what if the Wessex of Alfred the Great had succumbed to Viking invasion in the battle-winter of 8701 or the surprise attack of winter 8778? What if Alfred, a fourth if not fifth son, had never been king? What if two heirs had succeeded in 924, 9559, or 975? What if Edmund had defeated Cnut in 1016? What if Cnut had not died relatively young in 1035, or both his sons had not died in their twenties? What if Edward the Confessor had had a son, or his nephew and chosen heir Edward the Exile had not died in 1057? Earl Harold Godwinson would have stood little chance of the throne in either case and Duke William even less. Events cast a long shadow - if the English elite had not been decimated by the wars of the 1000s and Cnuts takeover; King Edward would not have had his political power circumscribed as of 1042 by three powerful earls all nominees of Cnut who could call on more military resources than he could. Even if Harolds father, Godwin, had still been chief minister, as in reality, when Edward exiled him in 1051 he would have been unlikely to have fought his way back to power and again, Harold would never have been in a position to succeed as king in 1066.

The same applies to events before the Viking invasions which began in 865, though here the evidence is less clear particularly before c.650 and much has to be guesswork. Basic questions of political and social development have to be asked. Why did pre-850 England consist of so many petty kingdoms, when the incoming Germanic peoples (conquerors or settlers) managed to create one state in Francia? The notion of a stable heptarchy of seven English kingdoms has now been disproved, and it is clear that there were three major states Northumbria, Mercia and Wessex plus numerous smaller ones, some of which were temporarily or permanently absorbed by their larger neighbours. But what determined which kingdoms succeeded geography, greater resources, military structure, or a coherent, dynamic and long-lasting tradition of leadership transmitted successfully from one generation to the next over centuries? The era of settlement and conquest is particularly disputed, and the notion of monolithic ethnic cleansing of Romano-Britons by invading Germans is now thought far too simplistic. Possibly peaceful farmers and traders were as crucial as the traditional picture of war-bands and heroic leaders played up by literary tradition. But it is clear that leadership was crucial and in the initial century or two of state-formation dynamic war-leaders and statesmen briefly brought leadership of coalitions of smaller kingdoms to states which were later eclipsed, such as Kent, Sussex and East Anglia. Those larger and better-resourced states which soon emerged to prominence, particularly the Big Three, had turbulent histories rather than a smooth rise to power, with the dominance of first one and then another, secured and then lost by military means. Wessex, Northumbria, and Mercia all achieved temporary dominance within their regions only to lose it again, by dynastic luck, military misjudgement, or a coalition of their enemies. Northumbria was eclipsed temporarily by Mercia after military defeat in 64255, and permanently after defeat by the Picts in 685 which latter battle ended the chance of a North English state encompassing much of Scotland. Wessex, dominant in the South, was eclipsed twice after 592 and 688. Would Mercia the leading state through the eighth and early ninth centuries under Aethelbald, Offa the Great, and Coenwulf have lost its dominance to Wessex after 825 if its succession had been more stable? Could a stable Mercia under long-lived rulers succeeded by competent sons have prevented the rise of Wessex under Alfreds grandfather Egbert, and but for the Viking invasions would Wessex have ever united England?