Selected Works by Seyyed Hossein Nast in English

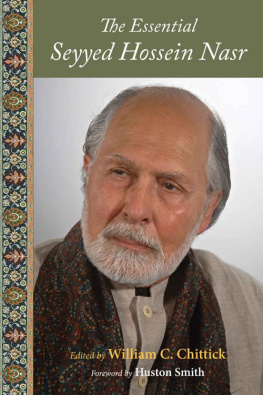

The Essential Seyyed Hossein Nasr (2007; ed. W. Chittick)

The Garden of Truth (2008)

The Heart of Islam (2004)

Ideals and Realities of Islam (2001)

An Introduction to Islamic Cosmological Doctrines (1993)

Islam: Religion, History, and Civilization (2003)

Islam and the Plight of Modern Man (2002)

Islamic Art and Spirituality (1987)

The Islamic Intellectual Tradition in Persia (1996)

Islamic Life and Thought (2001)

Islamic Philosophy from Its Origin to the Present (2006)

Islamic Science: An Illustrated Study (1995)

Islam, Science, Muslims, and Technology (2007)

Knowledge and the Sacred (1989)

Man and Nature: The Spiritual Crisis of Modern Man (1997)

Muhammad: Man of God (1988)

The Need for Sacred Science (1993)

The Pilgrimage of Life and the Wisdom of Rumi (2007)

Poems of the Way (1999)

Religion and the Order of Nature (1996)

Sadr al-Din Shirazi (1997)

Science and Civilization in Islam (1997)

Sufi Essays (1991)

Three Muslim Sages (1986)

Traditional Islam in the Modern World (1990)

A Young Muslim's Guide to the Modern World (1993)

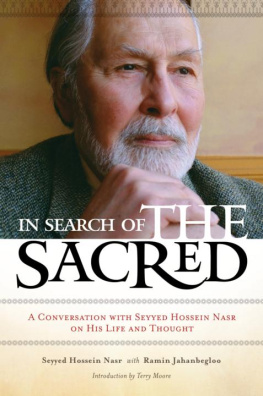

Seyyed Hossein Nasr with Ramin Jahanbegloo

Introduction by Terry Moore

xi

THE SPIRITUAL AND INTELLECTUAL JOURNEY OF SEYYED HOSSEIN NASR

G. K. Chesterton wrote: "There are two main moral necessities for the work of a great man: the first is that he should believe in the truth of his message; the second is that he should believe in the acceptability of his message." Seyyed Hossein Nasr has both. An Islamic philosopher of rare exemplarity, he has also been all through his life a man of dialogue with different faiths and diverse cultures. Not only has Nasr heralded a renaissance of Islamic sciences, but he has also been the agent and mediator through whom, in our day, the perennial philosophy has found a second birth. An unrelenting opponent of religious fundamentalism in all its forms throughout his career, Nasr presents his critique of modernity as a vision rooted in a traditional Muslim understanding of the world that respects both nature and human dignity.

For Nasr, the traditional world was based on an overwhelming sense of the Sacred and the Absolute, whereas the invention of modernity involved precisely the dissolution of that awareness, resulting in what Max Weber would call the "disenchantment of the world." Nasr's critique of modernity, while being a severe condemnation of secularism, is not a call for regression. Like his inspirers of the Perennialist School-Rend Gudnon, Amanda K. Coomaraswamy, and Frithjof Schuon-Seyyed Hossein Nasr provides his reader with a rigorous definition of what he understands by the term tradition. Nasr considers tradition as the principal milestone for spiritual authenticity and an infinite source of grace. Tradition, as described by Nasr, is the whole structure of thought that articulates the concepts embodied in the world of myth and symbols. This is why, according to Nasr, there has always been in the history of mankind, before the rise of modernity, an esoteric aspect to all traditions that reached to God and understood all things in God. Since the secularization of the Christian tradition and the technoscientific domination of the world by the Western world in the last few hundred years, however, all traditions have been undergoing secularization.

Actually, Nasr's critique of secularization in the modern world is far from being an obscurantist attempt to idealize tradition. On the contrary, his attempt to reestablish the esoteric tradition has created new grounds for a genuine comparative study of religions. One begins to see here how much of Nasr's work has to do with tradition as something alive and a ceaselessly renewed insight. Nast would himself be the first to recognize that tradition is an ever renewed vision of life. He is in a sense himself a remarkable product of the living traditions of Iran and Islam. In fact, unlike his traditionalist and perennialist predecessors, he identifies closely with a unique religious tradition that is Islam, while being an active member of the Iranian society in the years before the 1979 Iranian Revolution. Still, Nast has subscribed all his life to Meister Eckhart's formula: "If you want the kernel, you need to break the husk." Unlike his teacher Frithjof Schuon, Nasr's point of departure has been Islam and not Advaita Vedanta. However, like Schuon, he believes in the multileveled structure of Reality and the Divine Will. Esoterism is for Nast nothing less than the most comprehensive grammar of the Self. Nasr's understanding of Schuon's notion of "quintessential esoterism" finds its true universalist perspective in the former's reading of famous Sufi thinkers such as Ibn `Arabi or Rumi. In his Tarjuwan al-ashes q, Ibn `Arabi sings:

Following the paths of Ibn `Arabi, Meister Eckhart, Rumi and others, Nast's opus is a quest for the "essential elements of communality" among religions and a demonstration of the "transcendent unity of religions" based on an interfaith dialogue. His philosophical work includes indeed both a metaphysical and an erudite demonstration of such communality at the summit of the great religious traditions and contains a strong response to the predominant relativism in today's world.

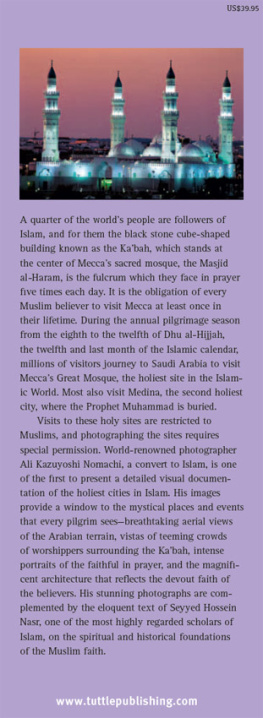

Another relevant aspect of Nasr's outlook is his spiritual journey toward sacred art. Very few authors have actually covered, in the manner and style of Seyyed Hossein Nasr, the highlighted themes of traditional art, architecture, calligraphy, music, poetry, and prose literature in Islamic lands. Nasr treats Islamic art as a manifestation of the unity of Islam. As in the case of Islamic sciences, Islamic art, according to Nasr, came into being from a wedding between the spirit that issued from the Quranic revelation and the artistic techniques that Islamic civilization inherited from the civilizations that preceded it, especially the Persian and the Byzantine. For him, both the arts and the sciences in Islam are based on the idea of unity, which is the heart of the Islamic revelation. To understand the Islamic arts and sciences in their essence, therefore, requires an understanding of some of the principles of Islam itself.