With love to my grandchildren,

Joel, Benjamin, Chloe, and Jeremy

Special thanks to the National Park Service

PHOTO AND ART CREDITS: pages 45: Akhararat Wathanasing/123RF; page 7: National Park Service; pages

8, 1213, 20, 24, 27: National Park Service/Jim Peaco; pages 11, 1415, 16: National Park Service/Jeff Henry;

pages 19, 2223: Gary Braasch; pages 2829: Kevin Fleming/Corbis; page 31: shaday365/123RF.

WILDFIRES. Copyright 1996, 2016 by Seymour Simon. All rights reserved under International and Pan

American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive,

non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be

reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any

information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now

known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

EPUB Edition 2016

ISBN: 9780062345035

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Revised Edition, 2016

Authors Note

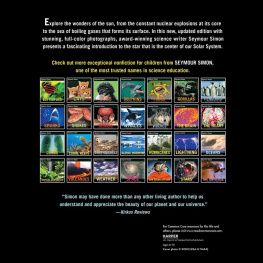

From a young age, I was interested in animals, space, my surroundings all the natural sciences. When I was a teenager, I became the president of a nationwide junior astronomy club with a thousand members. After college, I became a classroom teacher for nearly twenty- five years while also writing articles and books for children on science and nature even before I became a full- time writer. My experience as a teacher gives me the ability to understand how to reach my young readers and get them interested in the world around us.

Ive written more than books, and Ive thought a lot about different ways to encourage interest in the natural world, as well as how to show the joys of nonfiction. When I write, I use comparisons to help explain unfamiliar ideas, complex concepts, and impossibly large numbers. I try to engage your senses and imagination to set the scene and to make science fun. For example, in Penguins, I emphasize the playful nature of these creatures on the very first page by mentioning how penguins excel at swimming and diving. I use strong verbs to enhance understanding. I make use of descriptive detail and ask questions that anticipate what you may be thinking (sometimes right at the start of the book).

Many of my books are photo- essays, which use extraordinary photographs to amplify and expand the text, creating different and engaging ways of exploring nonfiction. Youll also find a glossary, an index, and website and research recommendations in most of my books, which make them ideal for enhancing your reading and learning experience. As William Blake wrote in his poem, I want my readers to see a world in a grain of sand, / And a heaven in a wild flower, / Hold infinity in the palm of your hand, / And eternity in an hour.

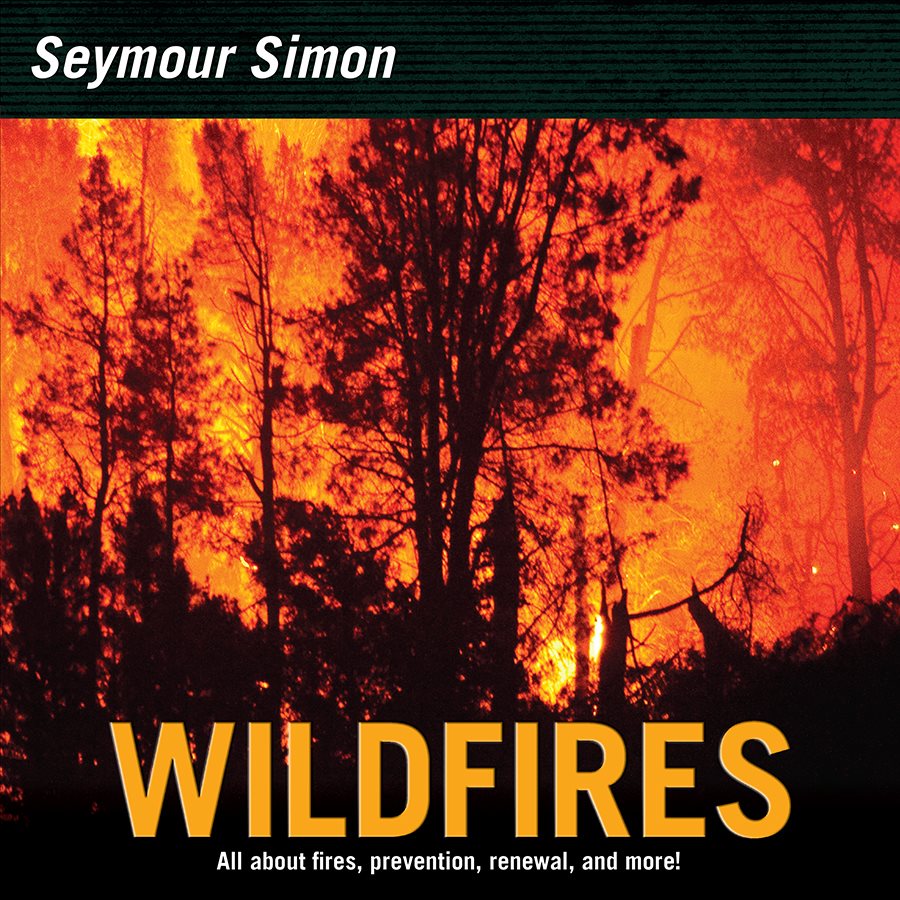

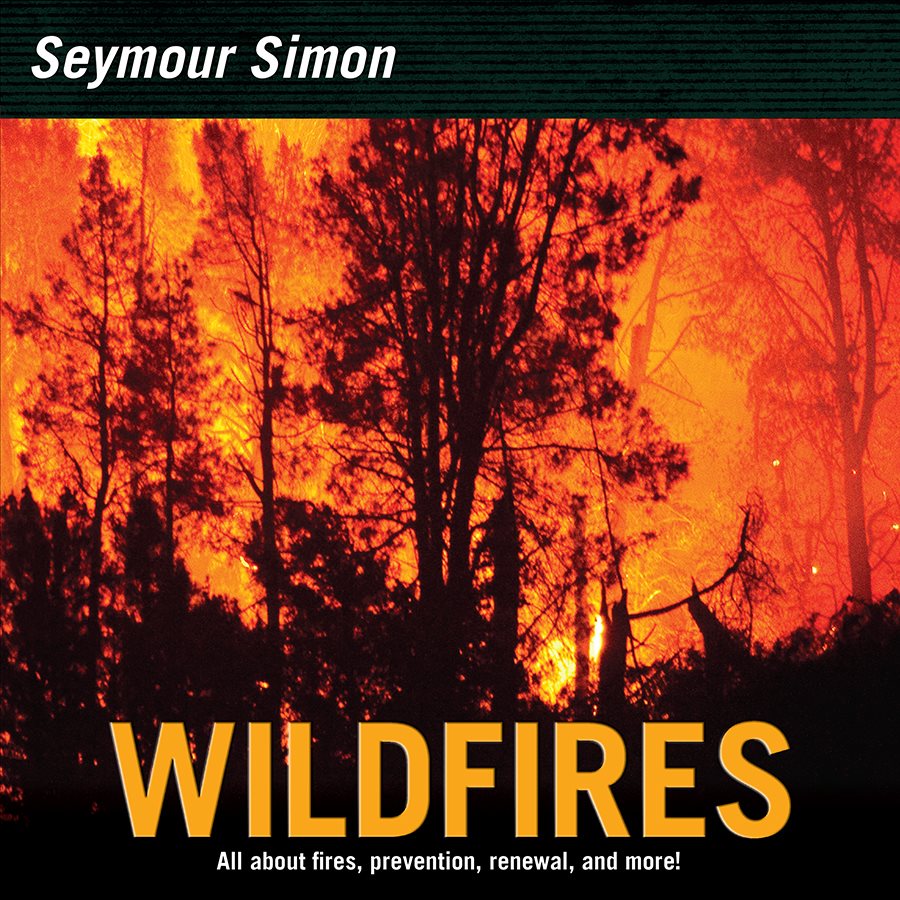

A raging wildfire is a frightening thing. Living trees burn as fast as cardboard boxes in a bonfire. Flames race through the treetops, sometimes faster than a person can run, burning at temperatures hot enough to melt steel. A wildfire can be a major disaster, capable of destroying hundreds of homes and costing human lives.

But not all fires are bad. Fires in nature can help as well as harm. A burned forest allows young plants to begin growing. And fire is necessary for some trees, such as sequoias, to release their seeds. Instead of being an ending, fire is often a new chapter in the continuing story of the natural world.

A fire is a chemical reaction, and it needs three things to burn: fuel, oxygen, and heat. During a fire, energy is released as heat and light, which is why fires are so hot and so bright. When a fire is done, there is often nothing left but ash. Ash is the form the fuel takes after the chemical reaction of fire is over.

Not only do fires release heat, but they are also caused by heat. A fire can be caused by a burning match, a flash of lightning, or a glowing ember in a dying campfire. Once a fire starts, the heat from the fire can cause other fires to start in nearby materials. A burning leaf can set fire to a nearby leaf without touching it, just from the intense heat. The flaming leaves can then set fire to a branch, which can set fire to the whole tree. In a short while, a fire can leap to another tree, and then another and another. A whole forest can be set ablaze from a tiny fire no bigger than the flame from a match.

Fires also need oxygen to burn. Oxygen is an invisible gas in the air we breathe. One of the reasons wet wood rarely burns is that the water prevents air from getting to the fire. Thats why water is used to fight fires in homes and in forests.

F or many years, Smokey Bear warned that only you could prevent forest fires, making people think that all fires were enemies. But wildfires are a fact of life in the wilderness, and plants and animals have adjusted to them. Many trees are so dependent on fires that they need cycles of fire in order to grow. Other kinds of trees and shrubs grow back quickly after a fire, often healthier than before. Most animals can survive forest fires by running or flying away or going underground and waiting out the fire as it passes. And plants that grow quickly after a fire provide food for animals that might otherwise starve.

In fact, aggressively fighting fires has probably decreased the number of wildfires that help a forest renew itself while increasing the number of more dangerous fires. Scientists say that by stamping out all fires as soon as they start, people have allowed leaves, dead wood, twigs, and bark to accumulate on the forest floor. This provides much more fuel to feed big wildfires than would be the case if small fires were allowed to burn naturally. A director of the United States Forest Service has said that it is not a question of whether these areas will burn, but only a question of when.