CONTENTS

Foreword by Michael Shermer

Chapter 1: 23

Chapter 2: 35

Chapter 3: 49

Chapter 4: 55

Chapter 5: 63

Chapter 6: 87

Chapter 7: 97

Chapter 8: 107

Chapter 9: 129

Chapter 10: 147

Chapter 11: 163

Chapter 12: 175

Chapter 13: 193

Chapter 14: 209

Chapter 15: 227

Chapter 16: 239

QUANTUM FLAPDOODLE

AND OTHER FLUMMERY

Foreword by Michael Shermer

n the spring of 2004, while on a book tour that took me to the square block-sized Powell's Bookstore in Portland, Oregon, I appeared on KATU TV's AM Northwest. In the green room, where they mix authors with chefs, pet trainers, and dating self-help gurus with a not-so-healthy dose of junk food and coffee, I was introduced to the producers of a documentary film improbably named What the Bleep Do WeKnow.l2They were pleasant enough fellows who seemed pleased to meet an editor of Scientific American because, they said, their film was about quantum physics. At the time I recall thinking, "A documentary film on quantum physics screening in a large public theater in competition with Hollywood films? This won't make it to the second weekend."

n the spring of 2004, while on a book tour that took me to the square block-sized Powell's Bookstore in Portland, Oregon, I appeared on KATU TV's AM Northwest. In the green room, where they mix authors with chefs, pet trainers, and dating self-help gurus with a not-so-healthy dose of junk food and coffee, I was introduced to the producers of a documentary film improbably named What the Bleep Do WeKnow.l2They were pleasant enough fellows who seemed pleased to meet an editor of Scientific American because, they said, their film was about quantum physics. At the time I recall thinking, "A documentary film on quantum physics screening in a large public theater in competition with Hollywood films? This won't make it to the second weekend."

How wrong I was. What the Bleep Do We Know.!? went on to become one of the highest grossing documentary films of all time. How can this be? Is the public suddenly interested in quantum physics? No. The explanation is to be found in the fact that the film is not really about quantum physics. The documentary's central motif is that we create our own reality through will, thought, and consciousness, which, according to the "experts" who appear as talking heads throughout the film (most of whom are not scientists, let alone quantum physicists), depends on quantum mechanics, that branch of physics so befuddling even to those who do it for a living that it can be invoked whenever something supernatural or paranormal is desired.

The Caltech Nobel laureate Murray Gell-Mann once described the misuse and abuse of quantum physics as "quantum flapdoodle." Examples from the film abound. The University of Oregon quantum physicist Amit Goswami, for example, says: "The material world around us is nothing but possible movements of consciousness. I am choosing moment by moment my experience. Heisenberg said atoms are not things, only tendencies." In my monthly column in ScientifacAmerican, I publicly challenged Dr. Goswami to leap out of a twenty-story building and consciously choose the experience of passing safely through the ground's tendencies. To my knowledge he has not taken me up on this experimental protocol. (In such an experiment you would most definitely want to be in the no-jump control group.)

Quantum flapdoodle infuses New Age gurus such as Deepak Chopra (whose quantum theory that aging is all in the mind is belied by the fact that he appears to be aging like everyone else), J. Z. Knight (masquerading as "Ramtha," the 35,000-year-old spirit warrior dishing out spiritual advice ... for a price, of course), and Masura Emoto, the Japanese author of The Message of Water, who believes that thoughts change the structure of ice crystals-beautiful crystals form in a glass of water with the word "love" taped to it, whereas playing Elvis's "Heartbreak Hotel" causes a crystal to split into two. We are still awaiting replication of this research, not to mention publication of it in a peer-reviewed scientific journal. In the meantime, domo arigato, Mr. Emoto.

Moving beyond such New Age nuttiness, there have been serious attempts to link the weirdness of the quantum world (such as Heisenberg's uncertainty principle, which states that the more precisely you know a particle's position, the less precisely you know its speed, and vice versa) to mysteries of the macroworld (such as consciousness). A leading candidate to link the two comes from physicist Roger Penrose and physician Stuart Hameroff, whose theory of quantum consciousness is also featured in What the Bleep Do We Know.!? According to this highly speculative conjecture, inside our neurons are tiny hollow microtubules that may initiate a wave function collapse that leads to the quantum coherence of atoms, causing neurotransmitters to be released into the synapses between neurons and thus triggering them to fire in a uniform pattern, thereby creating thought and consciousness. Since a wave function collapse can only come about when an atom is "observed" (i.e., affected in any way by something else), the idea is that the "mind" (either in your head or out there in space-time somewhere) may be the observer in a recursive loop from atoms to molecules to neurons to thought to consciousness to mind to atoms.... Maybe the entire universe is one giant mind that brings itself into existence by thought alone. Or maybe not.

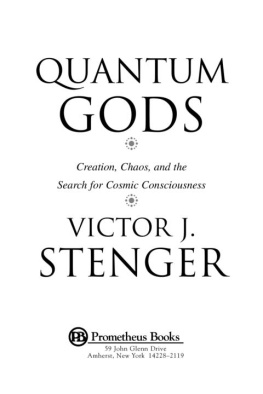

When I first looked into this idea for my column on What the Bleep Do We Know? in Scientific American, I called on the one man who knows both the science and the pseudoscience behind quantum physics, and that is Victor Stenger, who has single-handedly taken it upon himself to address each and every claim of the quantum flapdoodlists. For the Penrose-Hameroff conjecture, for example, Stenger explained to me that the gap between subatomic quantum effects and large-scale macrosystems is too large to bridge. Specifically, Stenger noted that for something to be described quantum mechanically, the system's typical mass m, speed v, and distance d must be on the order of Planck's constant h. "If mvd is much greater than h, then the system probably can be treated classically." Stenger computes that the mass of neural transmitter molecules, and their speed across the distance of the synapse, are about three orders of magnitude too large for quantum effects to be influential. There is no micro-macro connection. QE.D.

With this level of scientific and semantic precision Victor Stenger has taken on the God question in his book God. The Failed Hypothesis, addressing specific claims made for the Judeo-Christian God Yahweh in a systematic deconstruction that left them in tatters. As a result, Stenger's book rode the "New Atheist" Dawkins-driven wave to New York Times best-sellerdom. But Stenger added something new to this age-old debate, and that was a compelling argument for why there almost certainly is no God because of the contradictions inherent in the nature of God (or at least how God is portrayed in the Judeo-Christian worldview), as well as positive evidence that the universe does not need a creator-God.

But that was just a start for the polymathic Stenger. After all, Yahweh is just one among a pantheon of gods that have been conceived of in Western history, and in this, his latest masterpiece, Stenger picks up where he left off, addressing claims made for other gods, including and especially the sorts of arguments presented in What the Bleep Do We Know.!? to which he devotes an entire chapter that also serves as a brilliant tutorial in quantum physics, of which the great Nobel laureate Richard Feynman once said that no one really understands. That may be, but Victor Stenger does as good a job as anyone ever has in explaining it, and in the context of why quantum physics-along with chaos theory, complexity theory, emergence theory, and other assorted branches of physics, biology, and neuroscience-does not get you to God.

n the spring of 2004, while on a book tour that took me to the square block-sized Powell's Bookstore in Portland, Oregon, I appeared on KATU TV's AM Northwest. In the green room, where they mix authors with chefs, pet trainers, and dating self-help gurus with a not-so-healthy dose of junk food and coffee, I was introduced to the producers of a documentary film improbably named What the Bleep Do WeKnow.l2They were pleasant enough fellows who seemed pleased to meet an editor of Scientific American because, they said, their film was about quantum physics. At the time I recall thinking, "A documentary film on quantum physics screening in a large public theater in competition with Hollywood films? This won't make it to the second weekend."

n the spring of 2004, while on a book tour that took me to the square block-sized Powell's Bookstore in Portland, Oregon, I appeared on KATU TV's AM Northwest. In the green room, where they mix authors with chefs, pet trainers, and dating self-help gurus with a not-so-healthy dose of junk food and coffee, I was introduced to the producers of a documentary film improbably named What the Bleep Do WeKnow.l2They were pleasant enough fellows who seemed pleased to meet an editor of Scientific American because, they said, their film was about quantum physics. At the time I recall thinking, "A documentary film on quantum physics screening in a large public theater in competition with Hollywood films? This won't make it to the second weekend."