Sara Paretsky is the author of, most recently, Brush Back. A prolific crime and mystery novelist, she received her PhD in history from the University of Chicago in 1977.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2016 by Sara Paretsky

Afterword 2016 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2016.

Printed in the United States of America

25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-33774-6 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-33788-3 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226337883.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Paretsky, Sara, author.

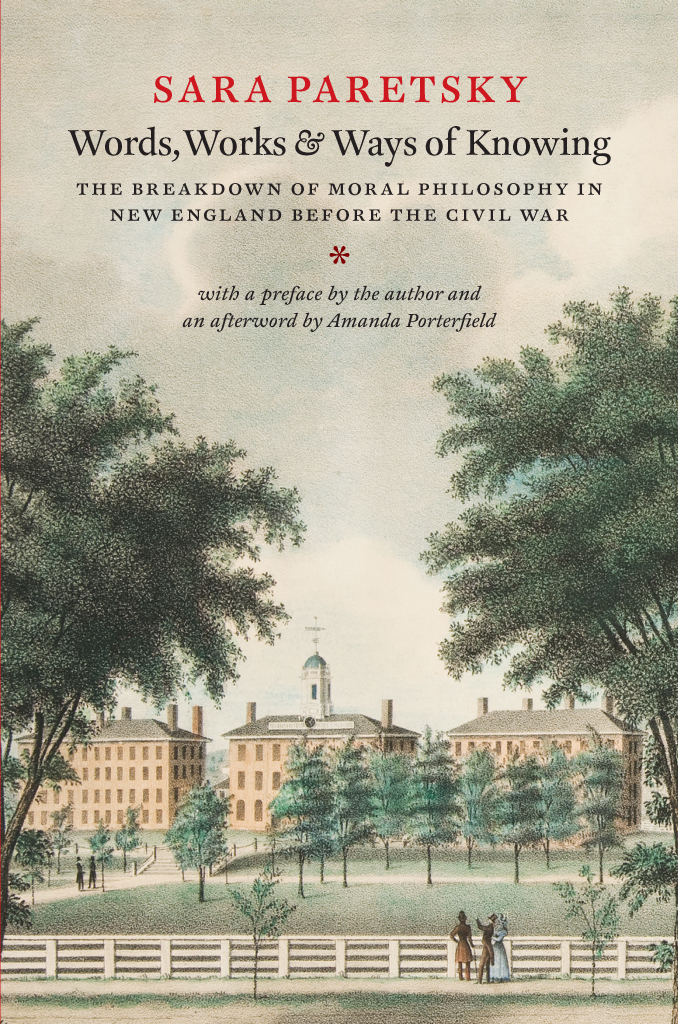

Title: Words, works, and ways of knowing : the breakdown of moral philosophy in New England before the Civil War / Sara Paretsky ; with a preface by the author and an afterword by Amanda Porterfield.

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015037376 | ISBN 9780226337746 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226337883 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: EthicsStudy and teachingNew EnglandHistory. | Andover Theological SeminaryHistory. | Learning and scholarshipNew EnglandHistory.

Classification: LCC BJ68.A53 P37 2016 | DDC 170.974/09034dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015037376

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

For Courtenay

All other things to their destruction draw,

Only our love hath no decay;

This, no tomorrow hath, nor yesterday,

Running it never runs from us away,

But truly keepes his first, last, everlasting day.

JOHN DONNE , The Anniversarie

:: :: ::

I was ten when I read my first work of history: Mark Twains Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc. True, its a romantic and sentimental version of the saint, but Twain did read all the original source material. His passion for Joan spoke to my own young experience and yearnings. Personal Recollections didnt make me want to be a historian, but it did make me long for a vision as great as hers and the passion to see it through to the end, evenor especiallyif the end were a pile of faggots in the old market of Rouen.

Almost everything Ive ever written has been part of this thirst for a vision, what the physicist Frank Wilczek calls a longing for the harmonies. Its the feeling you get from looking at the night sky, if youre lucky enough to see the stars hang down like living jewels, when you long to reach up and become part of that infinite jeweled space. The intensity of the feeling is part of adolescence, but the yearning has never completely left me, even in later age.

V. I. Warshawski, the detective I created in 1982 and who appears in seventeen of my novels, is a woman of action, but hers is an ardent spirit. Her passion for trying to right wrongs comes from a deeper thirst for creating a just world, a world of harmonies. In the novels, people mock her as Doa Quixote, or as Joan of Arc, but I dont write about her mockingly. She is the mirror of my own desires.

My novels also reflect another aspect of my life: the struggle to find a voice of my own, and to help other women gain the power to speak and to take up public space.

How the dissertation I wrote in the 1970s fits into the larger body of my postgraduate writing is a question that Ive had to think hard about. I came to the liberal theologians at the Andover Theological Seminary (today the site of Phillips Andover Academy) for a number of reasons. In part, I was drawn to religious thinkers because the saints and ascetics of Christian history seemed to have the same longings that I did. As an undergraduate, I used to study in the underground stacks in my universitys library. In that cave-like, quasi-monastic atmosphere, I read Calvins Institutes of the Christian Religion, the biographies of early Reformers like Thomas Cranmer, and the sermons of John Donne.

Still, why did I write a dissertation about men struggling with intellectual challenges to their religious beliefs? Why not take on Teresa of Avila, for instance, or, in the secular world, someone like Elizabeth Barrett Browning?

:: :: ::

I grew up in eastern Kansas in a family that valued the written word above almost any other good. We also were hearty eaters, so very often we read and ate at the same time.

I also grew up in a family that did not think the accomplishments or dreams of girls and women were worth attending to. I had four brothers whose education was important, but the expectations for me were limited to an old-fashioned model of circumscribed domesticity. I was expected to stay home to care for the house, the parents, the small brothers, and, despite winning a number of important scholarships, was essentially commanded to attend the University of Kansas.

I decided if I had to stay in Kansas for the academic year, Id spend my summers elsewhere. I was as tired as Charlotte Bront of a life confined to making puddings and knitting stockings.

The summer of 1966, I came to Chicago to work for the Presbytery of Chicago as a volunteer in the Civil Rights Movement. That was the summer that Martin Luther King, Jr., and his family moved into a tenement on the South Side while they tried to pry the city of Chicago out of its entrenched racist housing, employment, and other policies (these included barring blacks from most of the citys public beaches).

With two other college students, I was assigned to a mostly Polish and Lithuanian neighborhood only a few blocks from where Dr. King was living. We found ourselves with a front-row seat to some of the most violent confrontations of the Civil Rights Movement.

We were working with kids aged seven to eleven, and we took them all over the city by the L train, to the museums, the beaches, the ballparks. After hours, we were sent to meetings of the local white citizens council, the local aldermans constituency meetings, Black Power meetings, and to schools and stock exchanges and slaughter yards.

Although it was a summer of violence, it was also a time of hope: the possibility of change seemed real and exciting. Our work that summer and our engagement with the city gave me a deep attachment to Chicago. When I finished my undergraduate degree in January 1968, I came back; Chicago has been my home now for almost fifty years.

Because of my experience of Chicago during the race riots of 1966, I wanted to earn a PhD in US history. I wanted to try to understand the background of the violent divisions in the country. I had applied to a number of universities, but in 1968 I had taken a job as a secretary in the Social Science Division at the University of Chicago. Thanks to Emma Bickie Pitcher, with whom I worked, I received a Ford Foundation Fellowship and started graduate work at Chicago in the fall of 1968.