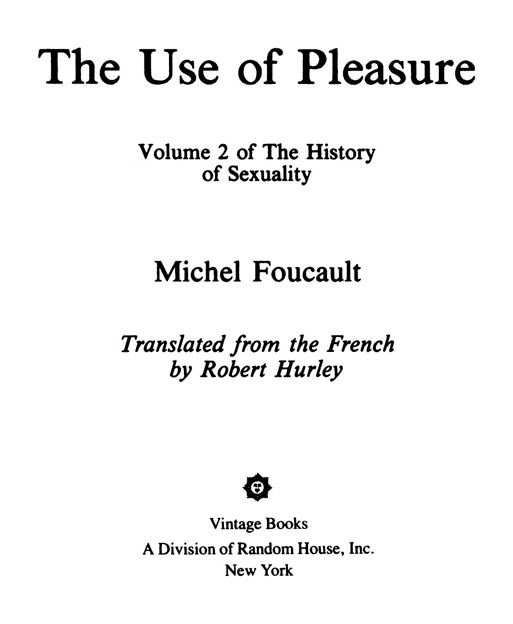

Books by Michel Foucault

Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason

The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences

The Archaeology of Knowledge (and The Discourse on Language)

The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception

I, Pierre Rivire, having slaughtered my mother, my sister, and my

brother. A Case of Parricide in the Nineteenth Century

Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison

The History of Sexuality, Volumes 1, 2, and 3

Herculine Barbin, Being the Recently Discovered Memoirs of a Nineteenth-Century French Hermaphrodite

Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 19721977

V INTAGE B OOKS E DITION , M ARCH 1990

Translation copyright 1985 by Random House, Inc.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright

Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a

division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in

Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally

published in France as LUsage des plaisirs by Editions Gallimard.

Copyright 1984 by Editions Gallimard. First American edition

published by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., in

October 1985.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Foucault, Michel. The history of sexuality.

Translation of Histoire de la sexualit.

Includes bibliographical references.

Contents: v. 1. An introductionv. 2. The use of pleasure.

1. Sex customsHistoryCollected works. I. Title.

HQ 12.F6813 1980 301.417 79460

eISBN: 978-0-307-81927-7

v3.1

Contents

Translators

Translators

AcknowledgmentsA number of people contributed to this translation, at Berkeley and elsewhere. Out of respect for the authors work, they made an occasion of community for which I am grateful.

Peter Brown generously shared his knowledge of classical matters and his familiarity with the authors project. His critical comments were an invaluable service.

Stephen W. Foster reviewed the translation with a practiced eye and suggested many changes of phraseology, virtually all of which I incorporated into the text.

Denis Hollier answered several questions that cropped up when my reading did not quite match the sophistication of the authors prose.

James Faubion drew up a list of reliable English versions of the major Greek texts. Without his recommendations, I would have risked many inaccuracies.

Marie-Claude Perigon, my wife, helped me with various problems of micro-interpretation, that is, with the kind of difficulties every reader encounters but only translators have to resolve.

I am indebted most to Paul Rabinow. He offered advice and encouragementmoral supportat every stage.

I wish to dedicate this English version to the memory of Michel Foucault.

R.H.

May 1985

Introduction

Introduction1

Modifications

This series of studies is being published later than I had anticipated, and in a form that is altogether different. I will explain why.

It was intended to be neither a history of sexual behaviors nor a history of representations, but a history of sexualitythe quotation marks have a certain importance. My aim was not to write a history of sexual behaviors and practices, tracing their successive forms, their evolution, and their dissemination; nor was it to analyze the scientific, religious, or philosophical ideas through which these behaviors have been represented. I wanted first to dwell on that quite recent and banal notion of sexuality: to stand detached from it, bracketing its familiarity, in order to analyze the theoretical and practical context with which it has been associated. The term itself did not appear until the beginning of the nineteenth century, a fact that should be neither underestimated nor overinterpreted. It does point to something other than a simple recasting of vocabulary, but obviously it does not mark the sudden emergence of that to which sexuality refers. The use of the word was established in connection with other phenomena: the development of diverse fields of knowledge (embracing the biological mechanisms of reproduction as well as the individual or social variants of behavior); the establishment of a set of rules and normsin part traditional, in part newwhich found support in religious, judicial, pedagogical, and medical institutions; and changes in the way individuals were led to assign meaning and value to their conduct, their duties, their pleasures, their feelings and sensations, their dreams. In short, it was a matter of seeing how an experience came to be constituted in modern Western societies, an experience that caused individuals to recognize themselves as subjects of a sexuality, which was accessible to very diverse fields of knowledge and linked to a system of rules and constraints. What I planned, therefore, was a history of the experience of sexuality, where experience is understood as the correlation between fields of knowledge, types of normativity, and forms of subjectivity in a particular culture.

To speak of sexuality in this way, I had to break with a conception that was rather common. Sexuality was conceived of as a constant. The hypothesis was that where it was manifested in historically singular forms, this was through various mechanisms of repression to which it was bound to be subjected in every society. What this amounted to, in effect, was that desire and the subject of desire were withdrawn from the historical field, and interdiction as a general form was made to account for anything historical in sexuality. But rejection of this hypothesis was not sufficient by itself. To speak of sexuality as a historically singular experience also presupposed the availability of tools capable of analyzing the peculiar characteristics and interrelations of the three axes that constitute it: (1) the formation of sciences (savoirs) that refer to it, (2) the systems of power that regulate its practice, (3) the forms within which individuals are able, are obliged, to recognize themselves as subjects of this sexuality. Now, as to the first two points, the work I had undertaken previouslyhaving to do first with medicine and psychiatry, and then with punitive power and disciplinary practicesprovided me with the tools I needed. The analysis of discursive practices made it possible to trace the formation of disciplines (savoirs) while escaping the dilemma of science versus ideology. And the analysis of power relations and their technologies made it possible to view them as open strategies, while escaping the alternative of a power conceived of as domination or exposed as a simulacrum.

But when I came to study the modes according to which individuals are given to recognize themselves as sexual subjects, the problems were much greater. At the time the notion of desire, or of the desiring subject, constituted if not a theory, then at least a generally accepted theoretical theme. This very acceptance was odd: it was this same theme, in fact, or variations thereof, that was found not only at the very center of the traditional theory, but also in the conceptions that sought to detach themselves from it. It was this theme, too, that appeared to have been inherited, in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, from a long Christian tradition. While the experience of sexuality, as a singular historical figure, is perhaps quite distinct from the Christian experience of the flesh, both appear nonetheless to be dominated by the principle of desiring man. In any case, it seemed to me that one could not very well analyze the formation and development of the experience of sexuality from the eighteenth century onward, without doing a historical and critical study dealing with desire and the desiring subject. In other words, without undertaking a genealogy. This does not mean that I proposed to write a history of the successive conceptions of desire, of concupiscence, or of libido, but rather to analyze the practices by which individuals were led to focus their attention on themselves, to decipher, recognize, and acknowledge themselves as subjects of desire, bringing into play between themselves and themselves a certain relationship that allows them to discover, in desire, the truth of their being, be it natural or fallen. In short, with this genealogy the idea was to investigate how individuals were led to practice, on themselves and on others, a hermeneutics of desire, a hermeneutics of which their sexual behavior was doubtless the occasion, but certainly not the exclusive domain. Thus, in order to understand how the modern individual could experience himself as a subject of a sexuality, it was essential first to determine how, for centuries, Western man had been brought to recognize himself as a subject of desire.

Next page