AFTER BUDDHISM

AFTER BUDDHISM

RETHINKING THE DHARMA FOR A SECULAR AGE

Stephen Batchelor

Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of Philip Hamilton McMillan of the Class of 1894, Yale College.

Copyright 2015 by Stephen Batchelor.

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

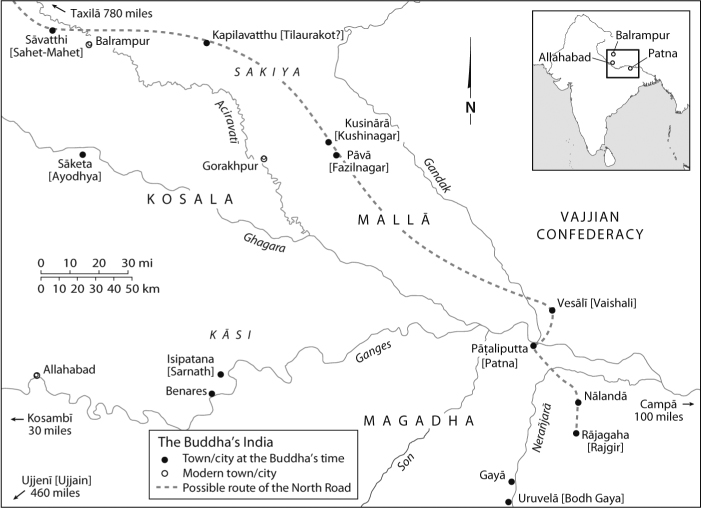

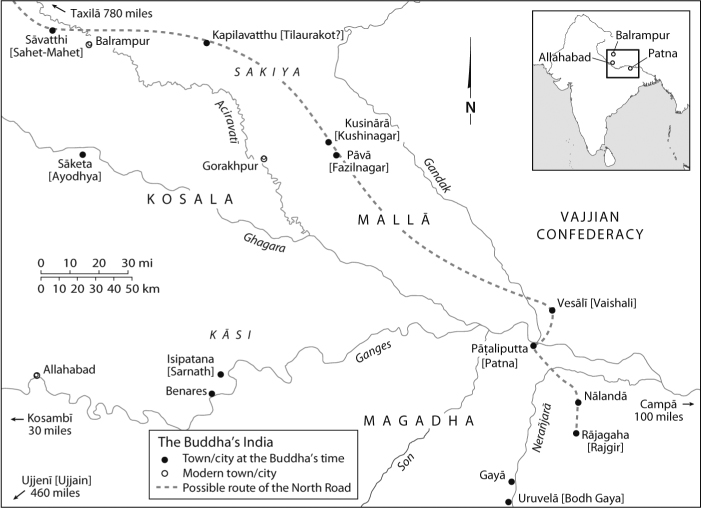

Map by Bill Nelson.

Designed by Mary Valencia.

Set in Scala type by Integrated Publishing Solutions.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015935009

ISBN 978-0-300-20518-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO

Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Don Cupitt

The dharma is clearly visible, immediate, inviting, uplifting, to be personally sensed by the wise.

Gotama, the Buddha (c. 480c. 400 BCE)

The dharma of the buddhas has no special undertakings. Just act ordinarily, without trying to do anything in particular. Move your bowels, piss, get dressed, eat your rice, and if you get tired, lie down.

Linji Yixuan (d. 866)

CONTENTS

PREFACE

This book is an attempt to synthesize an understanding of Buddhism that I have been working toward since my first publication, Alone with Others, appeared in 1983. In the intervening thirty years I have published a number of other writings that have branched off in different directions but maintained, at least in the eyes of the author, a steady focus on a single question: What does it mean to practice the dharma of the Buddha in the context of modernity? My most recent publication, the essay A Secular Buddhism (2012), can be seen as a preparatory sketch of what I seek to flesh out in this book.

I am indebted to Geshe Tamdrin Rabten for training me in Tibetan Buddhist logic, epistemology, and philosophy, which provided the intellectual foundations for everything I have done since; Satya Narayan Goenka for introducing me to the practice of vipassan and the early Buddhism of the Pali Canon; and Kusan Sunim for instructing me in the practice of Korean Sn (Zen), which, together with mindful awareness, continues as the basis for my practice of meditation. While all of these Buddhist traditions have played an important role in my understanding and practice of the dharma, my interpretations of certain Buddhist doctrines may strike some readers as highly unorthodox.

My primary authority for understanding what the Buddha taught is the discourses of the Pali Canon. My inability to read Chinese is the only reason I have not consulted the comparable body of texts preserved in the gama literature. The early records of the Sn Buddhist tradition, composed during the Tang dynasty of China, likewise serve as an important source for my work. For the later Indian tradition, I have been inspired by the writings of Ngrjuna and ntideva.

I have been influenced in my interpretations of Buddhism by the philosophers Martin Heidegger and Richard Rorty, as well as the Christian theologians Paul Tillich and Don Cupitt. In the field of Buddhist studies, I owe a debt of gratitude to the work of Richard Gombrich, K. R. Norman, Johannes Bronkhorst, and Gregory Schopen. I have been greatly helped in my understanding of the Pali Canon by the translations of Bhikkhu Bodhi, Eugene Watson Burlingame, I. B. Horner, John D. Ireland, Bhikkhu  amoli, Caroline Rhys Davids, and Maurice Walshe, as well as by

amoli, Caroline Rhys Davids, and Maurice Walshe, as well as by  avira Theras interpretations of some of its key ideas.

avira Theras interpretations of some of its key ideas.

Throughout this book I accept Heinz Bechert and Richard Gombrichs dating of the Buddha as c. 480c. 400 BCE. In moving his dates eighty years nearer to our own time than those accepted by Buddhist tradition, Gotama becomes a contemporary of Socrates rather than Pythagoras, which brings him into closer proximity to the Wests own historical self-awareness. I have based the core narrative of the life of Gotama on the account in the Vinaya of the Mlasarvstavda school as preserved in Tibetan and translated by W. Woodville Rockhill in 1884. My previous book Confession of a Buddhist Atheist (2010) reconstructed the story of the Buddhas life entirely on the basis of Pali sources. The version presented by Rockhill differs in a number of details, but the story is essentially the same. Since these two textual traditions were preserved at opposite ends of the Indian subcontinent, and since their preservers had no contact with each other for centuries, both texts were presumably based on an earlier version that was probably extant until the time of Emperor Aoka (304232 BCE), who was born only a century or so after the death of the Buddha.

As a rule, I give most proper names and Buddhist technical terms , section 9. The discourse that tradition has titled Turning the Wheel of Dharma (Dhammacakkapavattana Sutta) I have rendered throughout as The Four Tasks. I provide a translation of this and other Pali texts to which I frequently refer in the appendix: Selected Discourses from the Pali Canon.

I would like to thank the following readers whose comments on the manuscript have contributed to the final form of the work: Darius Cuplinskas, Ann Gleig, Winton Higgins, Bernd Kaponig, Antonia Macaro, Ken McLeod, Stephen Schettini, John Teasdale, Gay Watson, Anne Wiltshire, and Dale Wright. Discussions over the years with my colleagues John Peacock and Marc Akincano Weber have been of great help in clarifying my understanding of early Buddhism. I am most grateful for the support of my agent, Anne Edelstein, as well as my editor, Jennifer Banks, copyeditor Mary Pasti, and the staff at Yale University Press. As always, I am indebted to the unconditional encouragement and tolerance of my wife, Martine. It goes without saying that any errors are my own.

AFTER BUDDHISM

1

AFTER BUDDHISM

So, Bhiya, should you train yourself: in the seen, there will be only the seen; in the heard, only the heard; in the sensed, only the sensed; in that of which I am conscious, only that of which I am conscious. This is how you should train.

UDNA

( 1 )

A well-known story recounts that Gotamathe Buddhawas once staying in Jetas Grove, his main center near the city of Svatthi, capital of the kingdom of Kosala. Many priests, wanderers, and ascetics were living nearby. They are described as people of various beliefs and opinions, who supported themselves by promoting their different views. The text enumerates the kinds of opinions they taught:

The world is eternal.

The world is not eternal.

Next page

amoli, Caroline Rhys Davids, and Maurice Walshe, as well as by

amoli, Caroline Rhys Davids, and Maurice Walshe, as well as by