Leo Strauss: Reading between the Lines

Michael A. Peters and J. G. York

An exoteric book contains then two teachings: a popular teaching of an edifying character, which is in the foreground; and a philosophic teaching concerning the most important subject, which is indicated only between the lines.

Leo Strauss, Persecution and the Art of Writing

Gradually it has become clear to me what every great philosophy so far has been: namely, the personal confession of its author and a kind of involuntary and unconscious memoir; also that the moral (or immoral) intentions in every philosophy constituted the real germ of life from which the whole plant had grown.

Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil

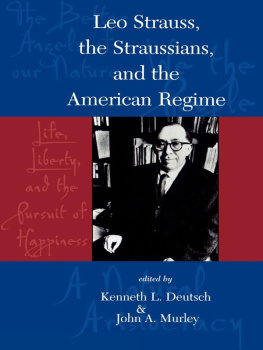

L EO STRAUSS'S BIOGRAPHY IS UNDOUBTEDLY CRUCIAL TO UNDERstanding both the man and his work. Strauss was raised as a Jew, and, while he was a student in Paris in the early 1930s, he studied both medieval Jewish and Islamic thought, later writing on Moses ben Maimonides and Abu Al-Nasr Al-Farabi and going on to formulate his notion of esoteric teaching. Strauss wrote on a variety of Jewish topics, including most famously Baruch Spinoza's Critique of Religion and his thesis on F. H. Jacobi (The Problem of Knowledge in F. H. Jacobi's Philosophical Teaching). He also offered commentaries on Zionism, Moses Mendelssohn, Hermann Cohen, and Franz Rosenzweig, among other related topics.

Perhaps of greatest significance was the Judaic influence on his statement of the theological-political problem (and tensions between philosophy and the city) that expressed a personal conflict he felt between the wisdom of premodern Abrahamic religion (specifically Judaism) and the rationality of Socratic philosophy.1 Indeed, Kenneth Hart Green argues that Strauss's return to Maimonides and premodern Judaism provided Strauss with a response to the crisis of modernity exposed by the radical historicism of Friedrich Nietzsche's and Martin Heidegger's thought. The synthesis of reason and faith of Mendelssohn that blended Enlightenment reason and Jewish orthodoxy provided Strauss with a model to guide modern Judaism through the problem of nihilism and the relativity of all values. It also provided Strauss with a basis for categorizing modern political philosophy and charting the crisis of liberal culture and its escape. Strauss also was strongly influenced by Cohen's Marburg neo-Kantianism, although even early in his development Strauss was aware of the phenomenological critique and he began to drift toward Zionism and Rosenzweig's theology.

These biographical facts about Strauss interpreted within the historical context of his Prussian birth, Jewish upbringing, and German higher education at Marburg and Freiburg clearly indicate that in his case understanding the biography and the context of a philosopher is an inestimable help in understanding his or her philosophical writing. This is a reference to a deeper understanding that connects the author to his or her intellectual environment and historical context. To know that Ernst Cassirer supervised his thesis, that he attended lectures by both Edmund Husserl and Heidegger, and that he associated with a group of influential German Jewish intellectuals, including Norbert Elias, Hannah Arendt, Leo Lwenthal, Walter Benjamin, Karl Lwith, Hans-Georg Gadamer, and Gershom Scholem, is immediately to provide a series of contextual clues to his philosophical sensibilities and an index to the major problems of the age. For Strauss philosophy, politics, and pedagogy were inextricably intertwine. It could be argued that his distinctiveness as a thinker is that he took these three subjects together, and his treatment of such infused his life and teaching. The fact that he understood the beginning of politics as that moment when Socrates was tried and sentenced to death for corrupting the youth of Athens is not a trivial philosophical or historical point linking the trio of philosophy, politics, and pedagogy. The connection is contemporaneous with the institutionalization of philosophy, esoteric knowledge, the manner of learning philosophy, and the political dangers of reason.

Ray Monk's (1990) Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius was the beginning of a significant historicist trend, against which Monk himself argues. He suggests: My biography of Wittgenstein was motivated in the first place by my feeling that his voice was being misheard (Monk, 2001), but then it makes clear that biography is, as he puts it, a profoundly nontheoretical activity (Monk, 2007). Yet, others see the interest in the biographical as part of a broader historicist approach and narrative turn to understanding the situatedness of the self, its spatiality as well as its temporality, and the central role of history, narrative, and experience in the shaping of moral consciousness and individual identity (Postel, 2002). Leo Strauss, his life and his works, are so inextricably tied together that it is difficult to separate out aspects of his ideas embodied in his published works from those of his courses or teaching.

Clearly, also, Strauss's own educational background as both a student and a professor is very formative in his own life and thinking. As a student Strauss completed his early schooling in a gymnasium near Marburg and attended university at Hamburg, and later both Marburg and Freiburg. He worked in various research posts in Berlin, Paris, and England (University of Cambridge) before moving to the United States in 1937, when he took a research position at Columbia and later a teaching position at the New School for Social Research in New York for the decade 193848. In 1949 he became a professor of political science at the University of Chicago, where he taught for twenty years. He also held positions at Claremont McKenna College (196970) and St. John's College, Annapolis, Maryland, where he was a scholar in residence from 1970 until his death in 1973.

These biographical details have been well turned over and theorized by a range of authors who provide intellectual biographies and discussions of his work. There has been a flowering of books on Strauss in recent years by those who praise him and those who criticize him, by his ex-student supporters and by his detractors, by those who seek to elucidate his political philosophy and by those who seek to expose his alleged relationship to neoconservatism (Drury, 1999; Janssens, 2008; Lampert, 1996; Meier, 2006; Norton, 2004; Pangle, 2006; Sheppard, 2006; Smith, 2006; Tanguay, 2005; Zuckert and Zuckert, 2006). Strauss's life was eventful, and his work occasioned both strong support and opposition during his life and after. Miles Burnyeat's review of Strauss's Studies in Platonic Political Philosophy for the New York Review of Books (32, 9, May 30, 1985) entitled Sphinx without a Secret, for example, created a backlash from Strauss's supporters, including replies by Allan Bloom, Joseph Cropsey, Robert Gordis, Harry V. Jaffa, Clifford Orwin, Thomas L. Pangle, and others (New York Review of Books, 32, 15, October, 1985). Burnyeat criticized Strauss on the role of the philosopher in Plato's Republic, among other ideas, and Joseph Cropsey wrote in response to Burnyeat's review:

M. F. Burnyeat's review of Leo Strauss's Studies in Platonic Political Philosophy [NYR, May 30] bears the same relation to Mr. Strauss's thought that the accompanying caricature bears to Strauss's person. Whoever knows or knew the original must be offended by a travesty generated apparently between levity and a gift for deforming the normal. By his deed Mr. Burnyeat vindicates what in words he denounces, namely, Strauss's view that a serious thought needs to be veiled against ill-natured levity, and Strauss's insistence that the student (a fortiori the critic) take the trouble to grasp the author's meaning, i.e., to understand him as he understood himself, before undertaking to discuss that author's work. By the method of parading elaborated reflections as adages jejune and assertoric, Mr. Burnyeat holds them up to ridicule, as he does Mr. Strauss's references to gentlemen and philosophers, unworthily lampooning those words by putting them in quotation marks as if they cannot be used without the apology implicit in that tendentious punctuation.

Next page