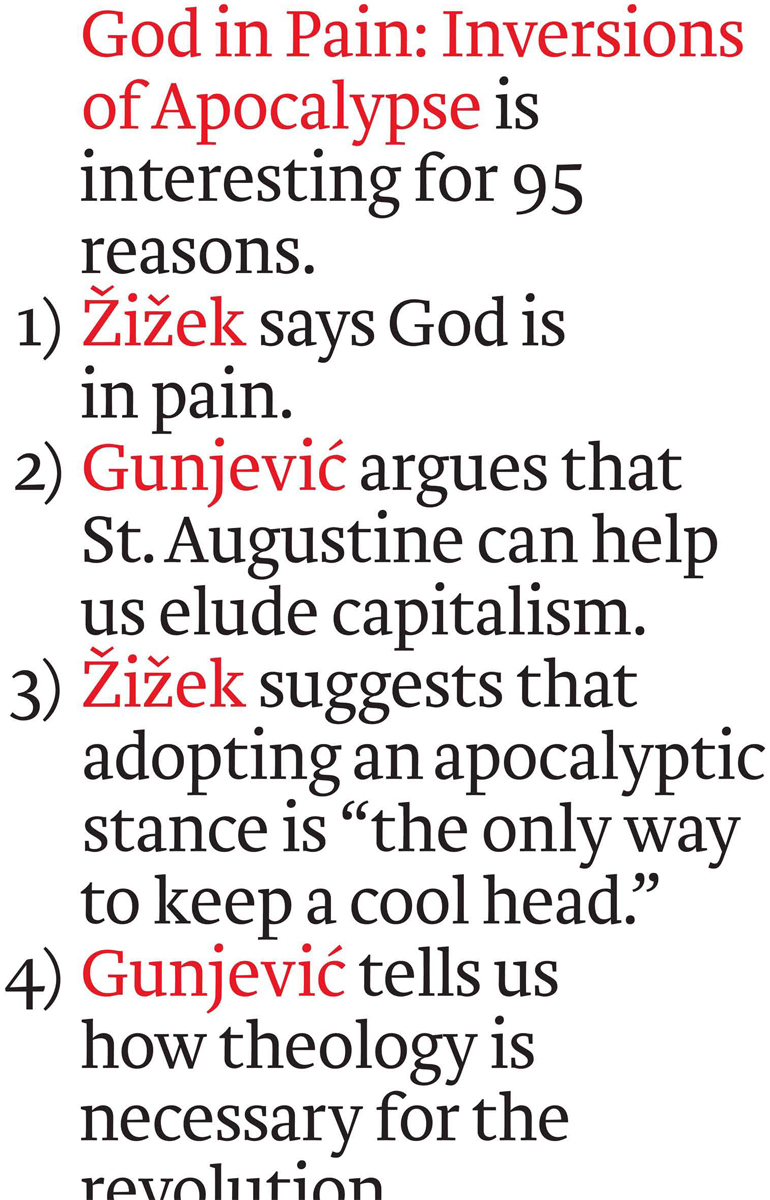

God in Pain

Inversions of Apocalypse

SLAVOJ IEK and

BORIS GUNJEVI

Boris Gunjevi s chapters translated from the Croatian by Ellen Elias-Bursa

s chapters translated from the Croatian by Ellen Elias-Bursa

Seven Stories Press

New York

Copyright 2012 by Slavoj iek and Boris Gunjevi

A Seven Stories Press First Edition

The publication of this book is supported by a grant from the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Croatia.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including mechanical, electric, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Seven Stories Press

140 Watts Street

New York, NY 10013

www.sevenstories.com

College professors may order examination copies of Seven Stories Press titles for a free six-month trial period. To order, visit http://www.sevenstories.com/ textbook or send a fax on school letterhead to (212) 226-1411.

Book design by Elizabeth DeLong & Jon Gilbert

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

iek, Slavoj.

[Bog na mukama. English]

God in pain : inversions of Apocalypse / Slavoj iek and Boris Gunjevic; Boris Gunjevics chapters translated from the Croatian by Ellen Elias-Bursac. -- A Seven Stories Press 1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-60980-369-8 (pbk.) -- ISBN 1-60980-369-8 (pbk.)

1. Religion and politics. 2. Religion--Philosophy--History. I. Gunjevic, Boris,

1972- II. Title.

BL65.P7Z5913 2012

200.1--dc23

2012001513

Printed in the United States

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Introduction

For a Theologico-Political Suspension of the Ethical

Slavoj iek

If, once upon a time, we publicly pretended to believe while privately we were skeptics or even engaged in obscene mocking of our public beliefs, today we publicly tend to profess our skeptical, hedonistic, relaxed attitude while privately we remain haunted by beliefs and severe prohibitions. Therein resides, for Jacques Lacan, the paradoxical consequence of the experience that God is dead:

The Father can efficiently prohibit desire only because he is dead, and, I would add, because he himself doesnt know itnamely, that he is dead. Such is the myth that Freud proposes to the modern man as the man for whom God is deadnamely, who believes that he knows that God is dead.

Why does Freud elaborate this paradox? In order to explain how, in the case of fathers death, desire will be more threatening and, consequently, the interdiction more necessary and more harsh. After God is dead, nothing is anymore permitted.

In order to properly understand this passage, one has to read it together with (at least) two other Lacanian theses. These dispersed statements should then be treated as pieces of a puzzle to be combined into one coherent proposition. It is only their interconnection plus the implicit reference to the Freudian dream of the father who doesnt know that he is dead that enables us to deploy Lacans basic thesis in its entirety:

(1) The true formula of atheism is not God is deadeven by basing the origin of the function of the father upon his murder, Freud protects the fatherthe true formula of atheism is God is unconscious.

(2) As you know,... Ivan leads [his father Karamazov] into those audacious avenues taken by the thought of the cultivated man, and in particular, he says, if God doesnt exist...If God doesnt exist, the father says, then everything is permitted. Quite evidently, a nave notion, for we analysts know full well that if God doesnt exist, then nothing at all is permitted any longer. Neurotics prove that to us every day.

The modern atheist thinks he knows that God is dead; what he doesnt know is that, unconsciously, he continues to believe in God. What characterizes modernity is no longer the standard figure of the believer who secretly harbors intimate doubts about his belief and engages in transgressive fantasies. What we have today is a subject who presents himself as a tolerant hedonist dedicated to the pursuit of happiness, but whose unconscious is the site of prohibitionswhat is repressed are not illicit desires or pleasures, but prohibitions themselves. If God doesnt exist, then everything is prohibited means that the more you perceive yourself as an atheist, the more your unconscious is dominated by prohibitions which sabotage your enjoyment. (One should not forget to supplement this thesis with its opposite: if God exists, then everything is permittedis this not the most succinct definition of the religious fundamentalists predicament? For him, God fully exists, he perceives himself as his instrument, which is why he can do whatever he wants, his acts are redeemed in advance, since they express the divine will...)

It is against this background that one can locate Dostoyevskys mistake. Dostoyevsky provided the most radical version of the If God doesnt exist, then everything is permitted idea in Bobok, his weirdest short story, which even today continues to perplex its interpreters. Is this bizarre morbid fantasy simply a product of the authors own mental disease? Is it a cynical sacrilege, an abominable attempt to parody the truth of the Revelation? In Bobok, an alcoholic literary man named Ivan Ivanovich is suffering from auditory hallucinations:

I am beginning to see and hear strange things, not voices exactly, but as though someone beside me were muttering, bobok, bobok, bobok!

Whats the meaning of this bobok? I must divert my mind.

I went out in search of diversion, I hit upon a funeral.

So he attends the funeral of a distant relative; remaining in the cemetery, he unexpectedly overhears the cynical, frivolous conversations of the dead:

And how it happened I dont know, but I began to hear things of all sorts being said. At first I did not pay attention to it, but treated it with contempt. But the conversation went on. I heard muffled sounds as though the speakers mouths were covered with a pillow, and at the same time they were distinct and very near. I came to myself, sat up and began listening attentively.

He discovers from these exchanges that human consciousness goes on for some time after the death of the physical body, lasting until total decomposition, which the deceased characters associate with the awful gurgling onomatopoeia, bobok. One of them comments:

The great thing is that we have two or three months more of life and thenbobok! I propose to spend these two months as agreeably as possible, and so to arrange everything on a new basis. Gentlemen! I propose to cast aside all shame.

The dead, realizing their complete freedom from earthly conditions, decide to entertain themselves by telling tales of their existence during their lives:

... meanwhile I dont want us to be telling lies. Thats all I care about, for that is one thing that matters. One cannot exist on the surface without lying, for life and lying are synonymous, but here we will amuse ourselves by not lying. Hang it all, the grave has some value after all! Well all tell our stories aloud, and we wont be ashamed of anything. First of all Ill tell you about myself. I am one of the predatory kind, you know. All that was bound and held in check by rotten cords up there on the surface. Away with cords and let us spend these two months in shameless truthfulness! Let us strip and be naked!

s chapters translated from the Croatian by Ellen Elias-Bursa

s chapters translated from the Croatian by Ellen Elias-Bursa