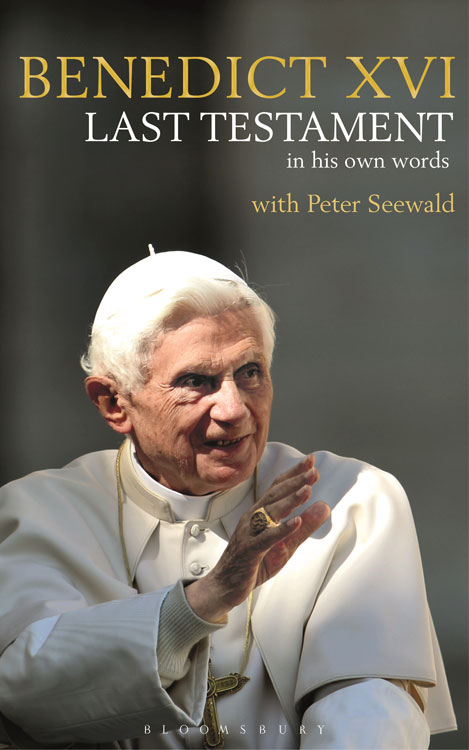

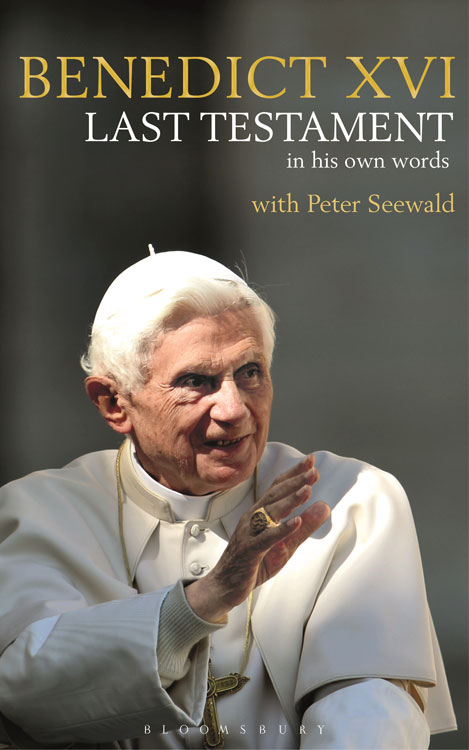

LAST TESTAMENT

LAST TESTAMENT

In his own words

Pope Benedict XVI

With Peter Seewald

translated by Jacob Phillips

Contents

Faith is nothing other than the touch of Gods hand in the night of the world, and so in the silence to hear the word, to see love.

Benedict XVI at the close of the Lenten retreat for the Roman Curia, before the end of his pontificate, 23 February 2013

A summer and a winter had passed, and as I once again made my way up the steep path to the Mater Ecclesiae convent in the Vatican Gardens on 23 May 2016, I was fearful that this could be our last full-length conversation.

Sister Carmela opened the door. She was not wearing an apron this time, but was dressed in elegant clothes. Hanging in the reception room was a picture of St Augustine, that great spiritual teacher who meant so much to Benedict XVI, because he too is driven by that dramatic human struggle to scrutinize the truth of the faith.

Instead of red slippers, he now wore sandals like a monk. He has been blind in his left eye for many years, he remembers less and less now, and meanwhile his hearing has diminished. His body had grown very thin, but his whole demeanour was tender like never before. And it was fascinating to see that this bold thinker, the philosopher of God, the first person to call himself Pope Emeritus, has arrived at last at a place where the intellect alone is not enough: a place of silence and prayer, the pulsing heart of faith.

It was November 1992 when I first encountered the then Prefect of the Faith. The editors of the magazine supplement to the Sddeutsche Zeitung wanted to publish an article about him, and I was to write it. On a list of applicants scrapping for an appointment with the most famous cardinal in the world were the names of journalists from the New York Times, Pravda and Le Figaro. I was hardly one to be considered particularly Catholic, but the more time I spent with Joseph Ratzinger, the more his sovereignty impressed me, as did his passion, and his courage to go against the grain with his old-fashioned thinking. And strangely, these findings were not only shocking, they also seemed to be right.

The much-maligned Panzerkardinal, understood properly, embodied not so much a relic from the past, as something for the future: a new intelligence for recognizing and articulating the mysteries of the faith. His speciality was the ability to unravel complicated issues, to see straight through mere superficialities. Science and religion, physics and metaphysics, thought and prayer Ratzinger brought these things together again in order to arrive at the genuine core of an issue. In the beauty of his language, the depth of his thinking leads one up to the heights. Theology, he explained, is pondering what God has said and thought before us. In order to be able to receive this freely, one must also be listening. If one is not only to impress people, but rather lead them to God, one needs the inspired Word.

Like Karol Wojtyla, Joseph Ratzinger had first-hand experience of the consequences of an atheist system. As a child he watched as crucifixes disappeared from schools, and when he was a seventeen-year-old soldier,

His life ran a dramatic course strewn with triumphs and failures, during which this highly gifted man understood himself to be one of those called to ascend to the chair of Peter.

There is the sensitive schoolboy who composes Greek hexameters and loves Mozart. The very young student who dreams of a Christian awakening among the bombed-out streets of Munich. The inquisitive model student, trained in the progressive thinking of the best theologians of the age, who broods for hours over books by Augustine, Kierkegaard and Newman. The unconventional curate who enthuses groups of young people. But also the devastated post-doctoral candidate, whose young career stands on the brink, threatened with collapse.

Destiny decreed things differently. In the blink of an eye the almost boyish-seeming professor from a tiny village in Bavaria becomes a rising star in the theological firmament.

People sit up and take notice: of the fresh-sounding phrases, the creative ways to enter into the gospel, and the authentic doctrine which he embodies. In the theology of a great thinker, wrote his mentor from Munich, Gottlieb Shngen, the substance and the form of theological thinking reciprocally interplay to shape a living unity. Ratzingers lecture halls are full to bursting. Written notes from his lectures are passed around, and copied out thousands of times by hand. His Introduction to Christianity excites Karol Wojtyla in the Acadmie des Sciences Morales et Politiques in Paris, an academy of the Institut de France which he will later join himself.

Ratzinger is just thirty-five years old when he is deeply stirred by the openness of the Second Vatican Council, which seeks to bring the Church into the modern world. No one besides this theological adolescent, a grateful John XXIII pointed out, was able to improve on the way Ratzinger expressed what the initiator of the Council actually intended.

While the theologians celebrated as progressives accommodated themselves to rather petit-bourgeois conceptions, and largely just served the mainstream, Ratzinger remained restless: as professor, as Bishop of Munich, and as Prefect for the Congregation of the Faith in Rome, where he kept John Paul IIs back covered for a quarter of a century and administered plenty of lashings. The real problem at this moment of our history, he warned, is that God is disappearing from the human horizon. By extinguishing the light of Gods approach, humanity is losing its bearings, with increasingly evident destructive effects.

This is necessary, he claimed, so that the active potency of the faith can be revealed again. We have to remain steadfast and unaccommodating, in order to demonstrate, without any frivolity, that Christianity is intertwined with a worldview that reaches beyond everything linked with a secular, materialistic attitude. The Christian worldview involves the revelation of the eternal God. It is nave to think you need only dress all in different clothes, speak as the world speaks, and then suddenly all will be well. We must find our way back to an authentic proclamation, and a liturgy that brings the radiant mystery of the mass to light.

The indictment he gave in contemplating the Via Crucis on Good Friday 2005 was unforgettable. How much filth there is in the Church, he cried out, and even among those who, being in the priesthood, ought to belong entirely to him.

The aged cardinal had become a sort of yardstick against which no one wanted to be assessed. But a few days after this call for self-examination and purification, he walked through the curtains of the loggia of St Peters Basilica as the 264th successor of the first apostle, before a jubilant throng of humanity. He was the little Pope, a simple worker in the vineyard of the Lord, following the towering Karol Wojtyla. He introduced himself to the 1.2 billion Catholics across the globe and he knew what needed to be done.

The new Pope made it clear that the true problems of the Church lie not in a dwindling membership, but in a dwindling faith. The extinguishing of a Christian consciousness is causing the crisis, the lukewarmness in prayer and worship, the neglect of mission. For him, true reform is a question of inner awakening, of setting hearts on fire. The top priority is to proclaim what we can know and believe with certainty about Christ.

Next page