Contents

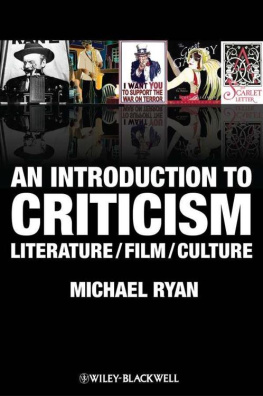

This edition first published 2012

2012 Michael Ryan

Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwells publishing program has been merged with Wileys global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell.

Registered Office

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex,

PO19 8SQ, UK

Editorial Offices

350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA

9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK

The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell.

The right of Michael Ryan to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ryan, Michael, 1951

An introduction to criticism : literature / film / culture / Michael Ryan.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-4051-8283-6 (hardback) ISBN 978-1-4051-8282-9 (paper)

1. Criticism. I. Title.

PN81.L93 2012

801.95dc23

2011035306

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

For Nathaniel

Preface

An Introduction to Critical Analysis

Criticism is the analysis of human cultural life. What science does to physical life criticism does to cultural life. It takes it apart and studies it and figures out why it works the way it does.

Such analysis ranges from the techniques used to make cultural artifacts such as novels, movies, music, and paintings to the ideas contained in such artifacts, the world out of which they arise, and their implications in our lives.

The specific region of culture that criticism analyzes is stitched into a larger cultural web that includes money, language, mathematics, engineering, commerce, digital computing, religion, and law. Without such culture in the larger sense, there would be no human life on earth. It is our most important creation as humans. It allows us to manipulate things without laying our hands on them, and it allows us to make the world work by using symbols or signs such as currency and words rather than hammers and levers.

The region of human culture that criticism addresses, the culture of plays, movies, novels, poems, public discourse, and songs, has an important function within that larger culture. It directs human thought, feeling, and belief in ways that help maintain human physical existence. It reinforces norms that guide behavior, and it remakes old assumptions about how we should behave that have lost their adaptive usefulness. Cultural artifacts promote ideas that motivate action and they provide moral instruction. They are teachers, ministers, advertisers, politicians, and parents all in one. They help us manage our lives by providing us with useful examples of how to live. Culture in this sense is akin to biochemistry. It does not do the actual work of life, but without the instructions it provides, that work could not occur.

The arts, including poems, novels, and plays, were invented at the same moment in human history as large-scale communities because the arts spread norms, and norms ensured that we humans could live together cooperatively. They allowed us to transcend our animal nature, which mandates violence and mutual predation for the sake of survival. To get beyond that stage of human existence, humans had to develop new cognitive powers, and one of the crucial powers was the ability to hold ideas and images in ones mind independently of things we perceive in the world. That kind of thinking ability led to the invention of religion; it made writing possible (seeing ideas in marks on a page); and it worked to invent laws based on ideal principles of justice. It also made norms possible, unwritten rules that were passed on through speech of various kinds such as oral tales and plays, as well as religious teaching and school instruction. Another name for the new cognitive ability that made cooperative civilized communities possible is imagination.

Cooperation is essential to human civilization because it makes larger human communities possible. Those communities were first enabled by changes in human cognition that made it possible for humans to use signs and to infuse objects with ideas. Strokes on paper became numbers that facilitated trade; signs in the marketplace became laws that were instructions for living properly; and certain ritual acts became embodiments of a regulating principle in human life Gods commandments that made people behave in ways useful to the survival of the community.

With what we call meaning the association of ideas with things was born the human ability to create large-scale civilizations. Large-scale human communities could only exist if all people held the same ideas of right and wrong in their minds. And religion, which might be called the first major human art form, provided such unanimity. It consisted of a mix of theater, fictional narrative, painting, and song. With time, actual theater supplanted it, and with even more time, modern cultural forms such as novels and movies took over the task of providing positive images of norms distinguishing right from wrong that sustain cooperative human communities still. The Great Gatsby teaches, among other things, that excess wealth is dangerous and destructive of human relations. It promotes a norm of moderate behavior.

As human civilization has developed over the past several millennia, culture has moved from unanimous meanings and beliefs that were largely religious in character to meanings that are multiple, complex, and contingent. Culture has become a realm where norms are debated as much as promoted. Societies held together by one religion are increasingly supplanted by ones in which multiple stories contend regarding what is true and good. As a result, the critical analysis of culture requires a variety of critical approaches. You will encounter them in this book.

Formalism

Major Texts

Viktor Shklovsky, Art as Technique

Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folk-Tale

Mikhail Bakhtin, Discourse in the Novel

Cleanth Brooks, The Well-Wrought Urn

Major Ideas

- Formalists pay attention to the how in how things are done. They notice form. When a ballerina executes the familiar moves of the dances in

Next page