Table of Contents

PENGUIN BOOKS

SEA OF CORTEZ

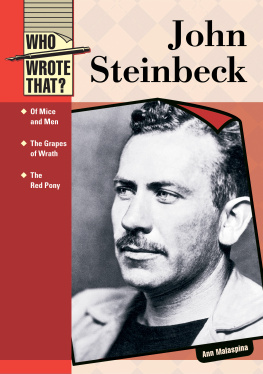

Born in Salinas, California, in 1902, John STEINBECK grew up in a fertile agricultural valley about twenty-five miles from the Pacific Coastand both valley and coast would serve as settings for some of his best fiction. In 1919 he went to Stanford University, where he intermittently enrolled in literature and writing courses until he left in 1925 without taking a degree. During the next five years he supported himself as a laborer and journalist in New York City and then as a caretaker for a Lake Tahoe estate, all the time working on his first novel, Cup of Gold (1929). After marriage and a move to Pacific Grove, he published two California fictions, The Pastures of Heaven (1932) and To a God Unknown (1933), and worked on short stories later collected in The Long Valley (1938). Popular success and financial security came only with Tortilla Flat (1935), stories about Montereys paisanos. A ceaseless experimenter throughout his career, Steinbeck changed courses regularly. Three powerful novels of the late 1930s focused on the California laboring class: In Dubious Battle (1936), Of Mice and Men (1937), and the book considered by many his finest, The Grapes of Wrath (1939). Early in the 1940s, Steinbeck became a filmmaker with The Forgotten Village (1941) and a serious student of marine biology with Sea of Cortez. He devoted his services to the war, writing Bombs Away (1942) and the controversial play-novelette The Moon Is Down (1942). Cannery Row (1945), The Wayward Bus (1947), The Pearl (1947), A Russian Journal (1948), another experimental drama, Burning Bright (1950), and The Log from the Sea of Cortez (1951) preceded publication of the monumental East of Eden (1952), an ambitious saga of the Salinas Valley and his own familys history. The last decades of his life were spent in New York City and Sag Harbor with his third wife, with whom he traveled widely. Later books include Sweet Thursday (1954), The Short Reign of Pippin IV: A Fabrication (1957), Once There Was a War (1958), The Winter of Our Discontent (1961), Travels with Charley in Search of America (1962), America and Americans (1966), and the posthumously published Journal of a Novel: The East of Eden Letters (1969), Viva Zapata! (1975), The Acts of King Arthur and His Noble Knights (1976), and Working Days: The Journals of The Grapes of Wrath (1989). He died in 1968, having won a Nobel Prize in 1962.

EDWARD F. RICKETTS was director of the Pacific Biological Laboratories, an institution which supplied marine specimens for many of the largest colleges and research laboratories in the country. He also coauthored, with Jack Calvin, Between Pacific Tides (1939).

BY JOHN STEINBECK

FICTION

The Grapes of Wrath

Las uvas de la ira (Spanish-language edition of The Grapes of Wrath)

The Acts of King Arthur and His Noble Knights

NONFICTION

Sea of Cortez: A Leisurely Journal of Travel and Research

(in collaboration with Edward F. Ricketts)

Bombs Away: The Story of a Bomber Team

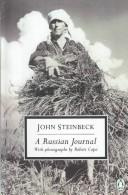

A Russian Journal (with pictures by Robert Capa)

The Log from the Sea of Cortez

Once There Was a War

Travels with Charley in Search of America

America and Americans

Journal of a Novel: The East of Eden Letters

Working Days: The Journals of The Grapes of Wrath

PLAYS

Of Mice and Men

The Moon Is Down

COLLECTIONS

The Portable Steinbeck

The Short Novels of John Steinbeck

Steinbeck: A Life in Letters

OTHER WORKS

The Forgotten Village (documentary)

Zapata (includes the screenplay of Viva Zapata!)

CRITICAL LIBRARY EDITION

The Grapes of Wrath (edited by Peter Lisca)

INTRODUCTION

THE design of a book is the pattern of a reality controlled and shaped by the mind of the writer. This is completely understood about poetry or fiction, but it is too seldom realized about books of fact. And yet the impulse which drives a man to poetry will send another man into the tide pools and force him to try to report what he finds there. Why is an expedition to Tibet undertaken, or a sea bottom dredged? Why do men, sitting at the microscope, examine the calcareous plates of a sea-cucumber, and, finding a new arrangement and number, feel an exaltation and give the new species a name, and write about it possessively? It would be good to know the impulse truly, not to be confused by the services to science plati tudes or the other little mazes into which we entice our minds so that they will not know what we are doing.

We have a book to write about the Gulf of California. We could do one of several things about its design. But we have decided to let it form itself: its boundaries a boat and a sea; its duration a six weeks charter time; its subject everything we could see and think and even imagine; its limitsour own without reservation.

We made a trip into the Gulf; sometimes we dignified it by calling it an expedition. Once it was called the Sea of Cortez, and that is a better-sounding and a more exciting name. We stopped in many little harbors and near barren coasts to collect and preserve the marine invertebrates of the littoral. One of the reasons we gave ourselves for this tripand when we used this reason, we called the trip an expeditionwas to observe the distribution of invertebrates, to see and to record their kinds and numbers, how they lived together, what they ate, and how they reproduced. That plan was simple, straight-forward, and only a part of the truth. But we did tell the truth to ourselves. We were curious. Our curiosity was not limited, but was as wide and horizonless as that of Darwin or Agassiz or Linnaeus or Pliny. We wanted to see everything our eyes would accommodate, to think what we could, and, out of our seeing and thinking, to build some kind of structure in modeled imitation of the observed reality. We knew that what we would see and record and construct would be warped, as all knowledge patterns are warped, first, by the collective pressure and stream of our time and race, second by the thrust of our individual personalities. But knowing this, we might not fall into too many holeswe might maintain some balance between our warp and the separate thing, the external reality. The oneness of these two might take its contribution from both. For example: the Mexican sierra has XVII-15-IX spines in the dorsal fin. These can easily be counted. But if the sierra strikes hard on the line so that our hands are burned, if the fish sounds and nearly escapes and finally comes in over the rail, his colors pulsing and his tail beating the air, a whole new relational exter nality has come into beingan entity which is more than the sum of the fish plus the fisherman. The only way to count the spines of the sierra unaffected by this second relational reality is to sit in a laboratory, open an evil-smelling jar, remove a stiff colorless fish from formalin solution, count the spines, and write the truth D. XVII-15-IX. There you have recorded a reality which cannot be assailedprobably the least important reality concerning either the fish or yourself.