To Wilson Menashi, who taught me so much about octopuses. S.M.

To a future diver and underwater explorer, my loving niece, Maya Ellenbogen. K.E.

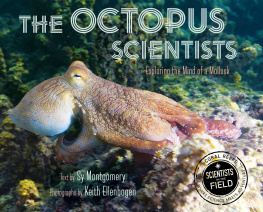

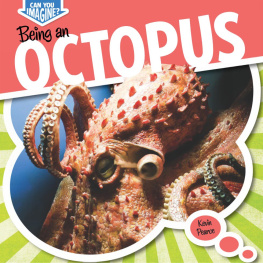

An octopus hiding in his home. Can you find him?

Text copyright 2015 by Sy Montgomery

Photographs copyright 2015 by Keith Ellenbogen

All rights reserved. For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhco.com

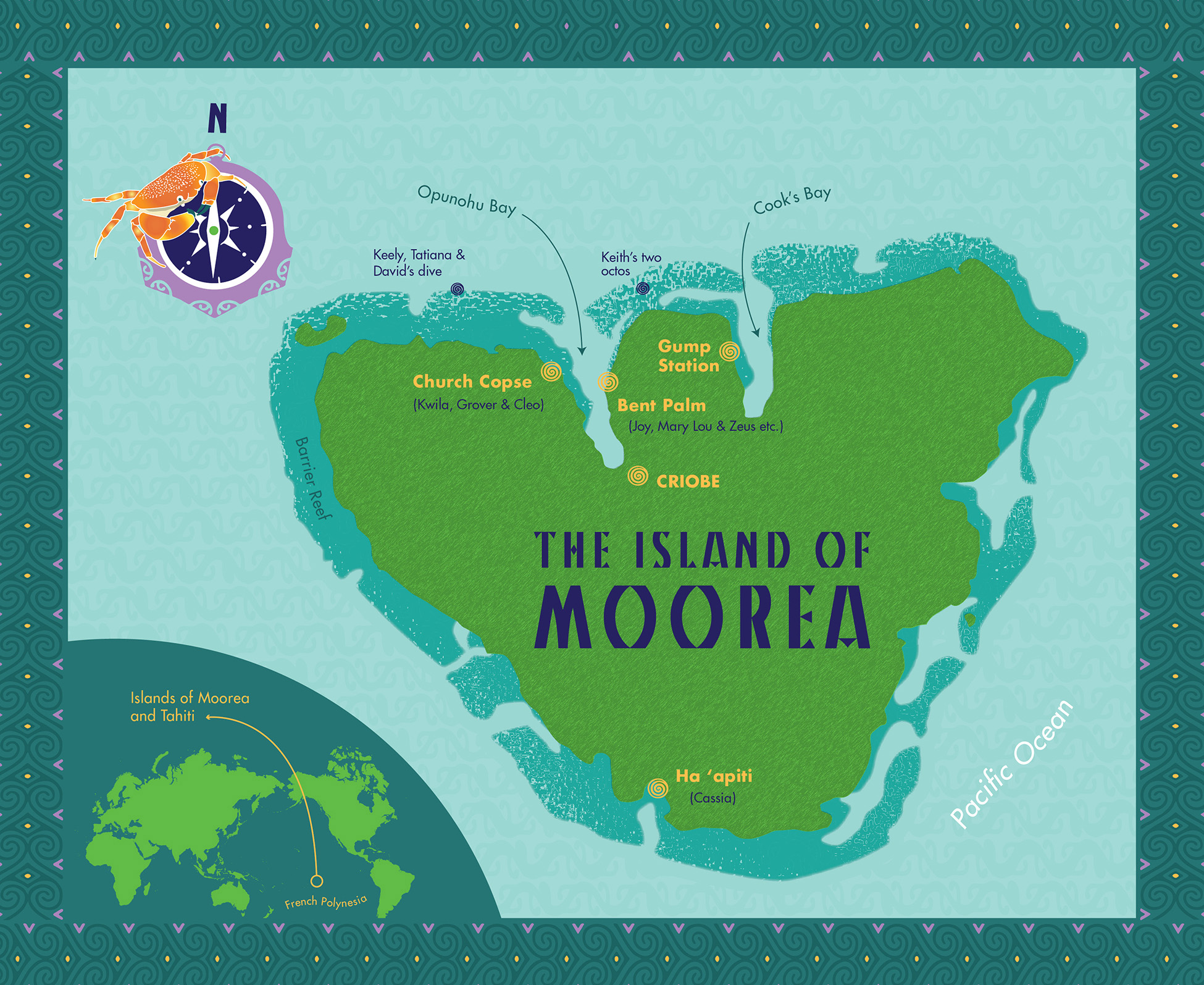

Map illustration by Rachel Newborn

Octopus tattoo diagram by Dave Mahan

Sidebar border and line space illustrations by Sy Montgomery

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file.

ISBN: 978-0-544-232-70-9

eISBN 978-0-544-66861-4

v1.0515

Chapter 1

The ocean is the worlds largest wilderness, covering 70 percent of the surface of the globe. But this vast blue territory is even bigger than it looks from land, or even from space. Its a three-dimensional realm that accounts for more than 95 percent of all livable space on the planetand most of it is unexplored.

The sea is home to creatures whose weirdness rivals that of the strangest sci-fi aliens anyone ever imagined. Were searching for one of them now: an animal with a baggy, boneless body, eight sucker-laden arms attached to its head, a beak like a parrot, and venom like a snake. It can shift its shape, change its color, squirt ink, and pour itself through the tiniest openingor shoot away through the sea by squirting water out of a flexible funnel, or jet, on the side of its head.

Were looking for octopusesthe Pacific day octopus, to be exact, one of perhaps 250 octopus species on the planet. Pacific day octopuses grow to more than four feet long. Theyre not rare or endangered. Should be pretty easy to find, right?

Ptttttthhhth!

A spout like a small whales shoots from her snorkel as Jennifer Mather pulls her silver-haired head from the water. She looks through her prescription facemask and waits for the rest of us to surface from the sea. Soon we answer her with a chorus of spouts.

Jennifer pulls the snorkel from her mouth. Find anything? she asks.

Around us stretches a tropical paradise of palm-fringed mountains. The islands waters teem with fish in neon colors and fantastic shapes. Honeymooners seek its warm blue sea, white beaches, and Polynesian food. But thats not what drew our team of six from three countries to the shallows here surrounding Moorea, a fifty-square-mile, roughly heart-shaped island twelve miles northwest of its much larger neighbor, Tahiti, in the South Pacific.

Jennifer Mather.

Nowe are out here looking for holes. Because where theres a hole, there might be an octopus.

That hole in the middle of that dead coral looks good, says Jennifer, pointing. Near it, she has found an empty shell. She holds it up to show us. That makes two pieces of evidence that suggest we could be closing in on our quarry. But it wont be as easy as it might seem.

What does our octopus look like? Well, thats the problem: Octopus cyanea (its named after Cyane, a water nymph in Greek mythology) might be fat and red, skinny and white, tall and brown, or a combination of colors and shapes. It might have stripes or spots or splotchesand then, the next second, it might look completely different. Or become utterly invisible.

Not only can it squeeze its three-foot-long arms and melon-size body through a hole the size of a thimble; it can also hide in plain sight. As well as changing color to match its surroundings, it can instantly sprout little projections all over its skin called papillae (pa-PIL-ay) to make it look exactly like a piece of algae or coral or rock.

Which is what the octopuses in this part of Opunohu Bay may be doing at this very momentif theyre here at all.

An octopus can jet away faster than a human swimmer can follow.

Octopuses are hard to find, concedes Jennifer. Though she works at the University of Lethbridge in the center of Canada, far from any ocean, shes been probing the mysteries of these quirky, changeable animals for forty years. Shes conducted experiments with the giant Pacific octopus, which can grow to more than one hundred pounds, in the Seattle Aquarium. Shes studied the five-inch-long pygmy octopus in Florida and the common octopus in Bermuda. And shes watched the Pacific day octopus before, off the island of Hawaii, and the common octopus off the Caribbean island of Bonaire.

Everything about them fascinates her, but especially this: Octopuses are smart, she saysand thats thought to be rare for invertebrates (in-VERT-a-brits). Invertebrates include insects, spiders, worms, snails, starfish, and clams; they have no bones, and usually have a very small brain. (Starfish and clams have no brain at all!)

Octopuses are in fact related to snails and clamstheyre all mollusks. Most mollusks have shellsbut not octos. That makes the octopus an unprotected packet of tasty protein for predators. Almost anything big enough can eat an octopus: along with its cousin, squid, it is the main prey of marine mammals, sharks, and many fish. Humans eat them too.

But what the octopus lacks in protective shell it makes up for in smarts. Actually, having no shell might be the very reason octopuses are so smart: they have to be. If youre a clam, you can just sit around, wait for food to float to you, and depend on your shell to protect you. Leaving the ancestral shell behind allowed octopuses more active lives, but also brought dangers demanding snap judgments. If a hungry shark approaches, should the octopus hide in a hole? Change color or shape? Release a smokescreen of ink? Or squirt a hanging blob of ink that looks like an octopuswhile the octopus itself jets away?

A small decorator crab might make a nice snack for an octopus.

To both hunt and hide, an octopus must choose wisely among many options, and it has evolved a big brain to help it do so. Jennifer, a professor of psychology, is interested in how these intelligent invertebrates make decisions. Thats why shes invited a team of octopus experts here to Moorea: to find out how octopuses decide what to eat... while avoiding being eaten themselves.

What good can come from studying the life of an octopus? There is an appalling amount we dont know about the ocean, says Jenniferso much so that the most elementary research might lead to unexpected breakthroughs.