I was able to write this book thanks to the generous study leave programs of the School of English and the Faculty of Arts at the University of Leeds. I spent some of my leave at the University of British Columbia, which gave me a perfect setting in which to write; my thanks to Alex Dick for his hospitality there. A remarkable group of people read drafts of the entire manuscript: Dipesh Chakrabarty, David Christian, Angela Clough, Ben Dibley, Alaric Hall, David Higgins, Daniel Lord Smail, Jan Zalasiewicz, and one other, anonymous reader for the University of California Press. Their expert revisions made the book much better than it would have been and saved me from many errors. I take full responsibility for the mistakes that no doubt remain. Anthony Carrigan, Alan Haywood, Jim Mussell, Stefan Skrimshire, and Graeme Swindles gave me valuable help and advice. Julia Banister kept telling me to make things clearer. Jamie Whyte drew the beautiful maps in chapters 4 and 5. Dore Brown, Bradley Depew, Bonita Hurd, and Niels Hooper have been an exemplary editorial team. I thank them all.

Introduction

This is a book about how to take the measure of a crisis. It is hard to grasp the scale of the modern environmental crisis, and part of the reason is that many things that had once seemed almost immutable are now changing rapidly.

The sea, for instance, is getting deeper. The worlds oceans are likely to grow in height by between 40 and 120 centimeters before the end of the present century, letting them spill onto coastal land, where cities have always clustered. The cycle of the seasons is changing. The times are out of joint for plants like the early spider orchid, which has evolved to deceive mining bees into pseudocopulation as its only means of pollination: warmer springs mean that the bees emerge too early to be seduced by the flowers that depend upon them. Similar decouplings threaten many other lifecycles, like those of the birds who now hatch their eggs too late to catch the caterpillars that feed their young. Even the map of the world is being redrawn. The rivers that sustained the Aral Sea have been diverted for irrigation, shrinking it to barely a tenth of its former size. Sand and salt from the exposed lake bottom, mixed with pesticides, heavy metals, and defoliants, now blow onto the surrounding farmlands, making crop yields plunge and afflicting local farmers with asthma, tuberculosis, eye problems, typhoid, Taken all together, this revolution that raises the oceans, reschedules the year, and turns water to land is bringing about a new epoch in the history of the world.

That last sentence might sound more declamatory than insightful, but in geology the word epoch has a specific technical meaning. A geological epoch is a midsize section of the planets history. Students of the earths biology and physical processes are now increasingly persuaded that the planetary system as a whole is undergoing an epoch-level transition. Earths atmosphere, oceans, rocks, plants, and animals are experiencing changes great enough to mark the ending of one epoch and the beginning of another. The present environmental crisis is epochal in this particular, specialized sense. It is hard to comprehend its magnitude, but if we regard current environmental changes as the birth pangs of a new epoch, and if we give that epoch its place in geological time, in the long history of the earth itself, we might start to make sense of what we are facing. Recognizing what is now ending and what is beginning can help us respond to the predicament of living in the fissures between one epoch and another. The incipient new division of geological time has already been given a name: the Anthropocene. The idea of the Anthropocene epoch lets us understand the ecological crisis of the present day in the context of the distant past.

The central argument of this book is that the idea of the Anthropocene provides both a motive and a means for taking a very, very long view of the environmental crisis. It gives the ecological upheavals of the present day their proper place in the history of the planet. If you want to grasp the force, the scale, and the shape of the catastrophe as it unfolds, look for how it opens a fresh chapter in the long sequences of planetary time. To make sense of climate change, biodiversity loss, rain forest logging, and the rest, pay attention to how the current and imminent states of the world compare to those seen in the various epochs that went before.

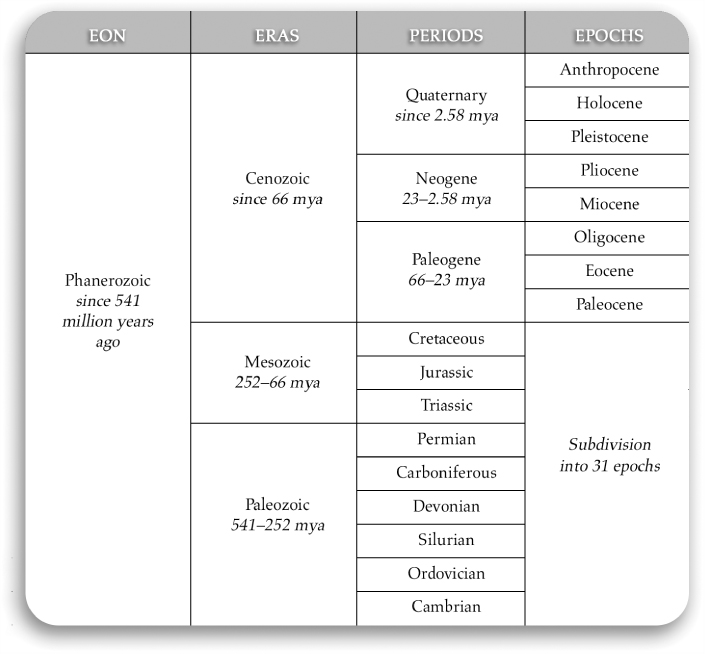

If contemporary environmental changes add up to the birth of a new geological epoch, then earth scientists should ready themselves to adjust the geological timescale, the diagrammatic summary of the history of the planet upon which the whole science of geology rests. For now, the Anthropocene is not included on the official chart of the timescale that is maintained by its designated custodians, the International Commission on Stratigraphy. But a simplified and abbreviated version of that chart, with the Anthropocene added to it, would look like the diagram in figure 1.

Figure 1. Phanerozoic eon.

Geological epochs such as the proposed Anthropocene are subsections of larger time units: periods, like the current Quaternary; eras; and ultimately eons. Epochs can themselves be subdivided into units called ages (not shown in this simplified diagram). All of these divisions and subdivisions come with fixed start dates and end dates, specified with greater or lesser margins of uncertainty according to the present state of geological knowledge. Evidently, when stratigraphersexperts in the physical sequences of rock strata upon which geological time sequences are builtpostulate the beginning of a new epoch, they are making a quite specific claim. They envisage introducing one new piece, of a certain size and shape, into the carefully wrought mosaic of the geological timescale. The significance of the new interval, like that of all the older ones, would depend in large part on when it was said to have begun. Its hierarchical status, too, would matter greatly: to declare a new epoch would be a smaller step than creating an Anthropocene period, but an epoch would loom larger in geologic time than a mere Anthropocene age. So when it is used by stratigraphers, the word Anthropocene designates an interval that would occupy one particular place within the immense volume of geological time.