Emma Donoghue - Inseparable: Desire Between Women in Literature

Here you can read online Emma Donoghue - Inseparable: Desire Between Women in Literature full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2010, publisher: Knopf, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Inseparable: Desire Between Women in Literature

- Author:

- Publisher:Knopf

- Genre:

- Year:2010

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Inseparable: Desire Between Women in Literature: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Inseparable: Desire Between Women in Literature" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Inseparable: Desire Between Women in Literature — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Inseparable: Desire Between Women in Literature" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Passions Between Women: British Lesbian Culture, 16681801

We Are Michael Field

Poems Between Women: Four Centuries of Love,

Romantic Friendship and Desire (editor)

The Mammoth Book of Lesbian Short Stories (editor)

Stir-fry

Hood

Ladies and Gentlemen

Kissing the Witch

Slammerkin

The Woman Who Gave Birth to Rabbits

Life Mask

Touchy Subjects

Landing

The Sealed Letter

Dedicated to my remarkable mother,

Frances Donoghue,

who has never asked me to put down a book

and do something useful.

)

David Henry Friston, in J. Sheridan LeFanu, Carmilla, in The Dark Blue (March 1872). (Courtesy of Yale University Library)

)

W HEN I WAS A SMALL CHILD I read fairy tales. I carried straining plastic bags of them home from the library every Saturday: Grimm, Perrault, Hans Christian Andersen, Arabian Nights, Brer Rabbit, Celtic myths, Polish folktales, Italian ones, Japanese, GreekSoon I started spotting repetitions. It thrilled me to detect the same basic shape (for instance, the motif of the selkie, or wife from the sea) under many different, exotic costumes. When I announced my discovery to my father, he broke it to me gently that others had got there first: a Russian called Vladimir Propp, and before him a Finn called Antti Aarne, who published his system of classifying folk motifs back in 1910. Ah well. This disappointment taught me, even more than the fairy tales had, that there is nothing new under the sun.

I remained a greedy reader, and when I found myself falling for a girl, at fourteen, I began seeking out stories of desire between women. The first such title I spent my hoarded pocket money on was a truly grim Dutch novel first published in 1975, Harry Mulischs Twee Vrouwen (in English, Two Women). Sylvia leaves Laura for Lauras ex-husband, Alfredbut, it turns out, only to get pregnant. The two women are blissfully reunited for a single evening of planning the nursery decor before Alfred turns up and shoots Sylvia dead, leaving Laura to jump out a window. Shaken but not dissuaded, I read on, for the next twenty years and counting. You would be forgiven for thinking that my book list must have been rather short. But the paradox is that writers in English and other Western languages have been speaking about this so-called unspeakable subject for the best part of a millennium.

What I am offering now in Inseparable is a sort of map. It charts a territory of literature that, like all undiscovered countries, has been there all along. This territory is made up of a bewildering variety of landscapes, but I will be following half a dozen distinct paths through it. Despite a suggestion in the New York Times in 1941 that the subject of desire between women should be classified as a minor subsidiary of tragedy, in fact it turns up across the whole range of genres. Reading my way from medieval romance to Restoration comedy to the modern novel, mostly in English (but often in French, and sometimes in translations from Latin, Italian, Spanish, or German), I uncover the most perennially popular plot motifs of attraction between women. Here they are, in a nutshell.

TRAVESTIES: Cross-dressing (whether by a woman or a man) causes the accident of same-sex desire.

INSEPARABLES: Two passionate friends defy the forces trying to part them.

RIVALS: A man and a woman compete for a womans heart.

MONSTERS: A wicked woman tries to seduce and destroy an innocent one.

DETECTION: The discovery of a crime turns out to be the discovery of same-sex desire.

OUT: A womans life is changed by the realization that she loves her own sex.

At this point you may wonder, are the women in these plays, poems, and fictions lesbians? Not necessarily, is how I would begin to answer. But perhaps we are better off postponing that question until we have asked more interesting ones. In the first five of my six chapters, I will be as shorthand, the twenty-first-century use of that word as a handy identity label does not begin to do justice to the variety of womens bonds in literature from the 1100s to the 2000s. The past is a wild party; check your preconceptions at the door.

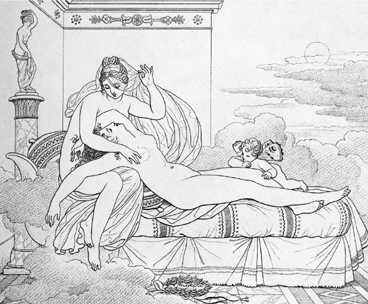

Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson (better known as Girodet-Trioson), Songe de Sapho [Sapphos Dream], engraved by Henri-Guillaume Chtillon, in Sappho, Bion, Moschus. Receuil de compositions dessines par Girodet [1827] (1829).

This is the third of the French Romantic painters designs in the antique vase style to accompany his translations from Sappho. They were published three years after Girodets death by his student, friend, and executor, Marie-Philippe Coupin de la Couperie, who claimed that this image showed Sappho in the arms of the goddess Venus, dreaming of her ideal husband.

It is customary to lament the fact that desire between women, before the twentieth century, was one long silence. After all, everyone has heard the story about Queen Victoria, whose ministers wanted to make lesbian sex illegal in 1885 but could not bring themselves to explain to her that it was even possibleExcept that it turns out that never happened. (Dating from 1977,that allows us to feel more knowledgeable and daring than our nineteenth-century ancestors.) On the contrary, literary researchers over the past few decades have unearthed a very long history of what Terry Castle calls the lesbian idea; her eleven-hundred-page anthology The Literature of Lesbianism (2003)by far the best availablecan only sample the riches.

In writing Inseparable, does not constitute a plot motif: I include only texts in which the attraction between women is undeniably there. It must also be more than a moment; it must have consequences for the story. The emotion can range from playful flirtation to serious heartbreak, from the exaltedly platonic to the sadistically lewd, but in every case it has to make things happen.

Take, for instance, The Man of Laws Tale, the fifth of the Canterbury Tales (1400) by courtier and diplomat Geoffrey Chaucer. It tells how Custance, daughter of a Christian Roman emperor and bride of the sultan of Syria, is cast adrift in a boat through her mother-in-laws machinations. Shipwrecked on the Northumberland coast, Custance immediately arouses the protective passion of Dame Hermengyld, the constables wife: Hermengyld loved hire as hir lyf. Over months of prayers and tears, Custance wins Hermengyld from paganism to Christianity, and Hermengyld manages to cure a blind man in the name of Jesuswhich prompts her husband to convert too. But a knight whom Custance has rejected is jealous of the womens closeness; he sneaks into the room where they are sleeping together and slits Hermengylds throat, leaving the bloody knife beside Custance to frame her for murder. The people are not fooled by this circumstantial evidence, since they have witnessed the womens relationship with their own eyes: For they han seyn hir evere so vertuous, / And lovyng Hermengyld right as hir lyf. (For they have seen Custance be virtuous all the time, and love Hermengyld as her life.) The peoples suspicion is confirmed by divine intervention: as the knight tells his lies in court, his eyeballs suddenly drop out of his head. This is an excellent example, perhaps the earliest in English, of how a mutual passion between two women can be not just an ornamental extra, but what moves the story along.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Inseparable: Desire Between Women in Literature»

Look at similar books to Inseparable: Desire Between Women in Literature. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Inseparable: Desire Between Women in Literature and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.