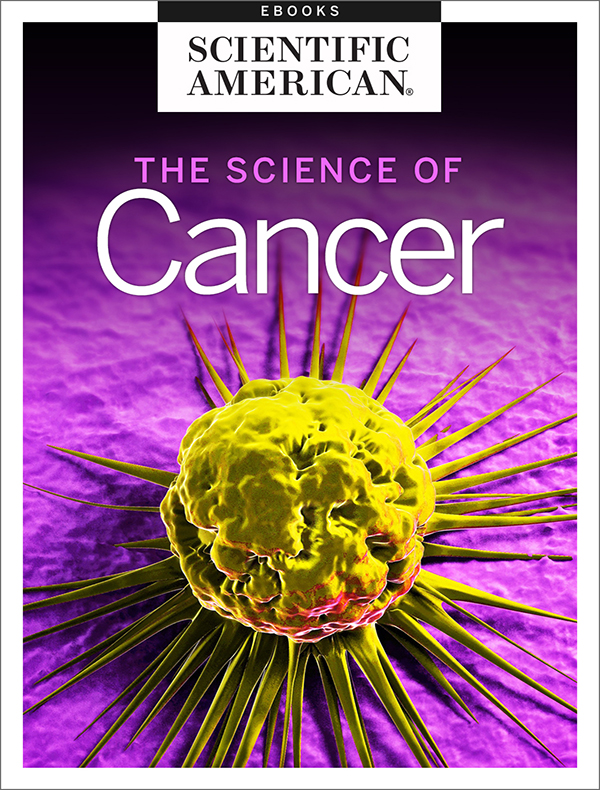

The Science of Cancer

From the Editors of Scientific American

Cover Image: SCIEPRO/Getty Images

Letters to the Editor

Scientific American

One New York Plaza

Suite 4500

New York, NY 10004-1562

or editors@sciam.com

Copyright 2017 Scientific American, a division of Nature America, Inc.

Scientific American is a registered trademark of Nature America, Inc.

All rights reserved.

Published by Scientific American

www.scientificamerican.com

ISBN: 978-1-4668-5907-4

THE SCIENCE OF CANCER

From the Editors of Scientific American

Table of Contents

Introduction

by Karin Tucker

Section 1

1.1

by W. Wayt Gibbs

1.2

by Robert A Weinberg

1.3

by Katherine Harmon

1.4

by Michael F. Clarke & Michael W. Becker

1.5

by Gary Stix

1.6

by Carl Zimmer

1.7

by Francis S. Collins & Anna D. Barker

Section 2

2.1

by Nancy Shute

2.2

by John Horgan

2.3

by Marc B. Garnick

Section 3

3.1

by Eric von Hofe

3.2

by Karen Weintraub

3.3

by Jedd D. Wolchok

3.4

by Christine Gorman

3.5

by Dina Fine Maron

3.6

by Douglas J. Mahoney, David F. Stojdl and Gordon Laird

Section 4

4.1

by Katherine Harmon

4.2

by Sophie Bushwick

4.3

by Katherine Harmon

4.4

by Katherine Harmon

4.5

by Dina Fine Maron

Science vs. the C Monster

The Cancer Moonshot, announced by President Barack Obama during his 2016 State of the Union Address, was an initiative to accelerate cancer research. Led by Vice President Joe Biden, the project aspired to make more therapies available to more patients, while also addressing how to prevent cancer and detect it at an early stage. Even at the dawn of a new administration, the $264-million cash infusion Biden secured for the National Cancer Institute will go a long way to assist cancer research. While most of todays research focuses on the genetic basis of cancer, epidemiologic studies point to a variety of environmental causes, including carcinogens like tobacco smoke, poor diet, obesity, radiation and pollutants. Even viral infections can cause certain types of cancer. With such a wide range of causes that need further research, the Cancer Moonshot is a welcome influx of resources. In this eBook, The Science of Cancer, we will explore the causes of cancer, the arguments for and against screenings, ongoing therapies, and prevention.

The first section is devoted to understanding the molecular basis of cancer and surveying its genetic origins. In Robert Weinbergs How Cancer Arises, he explains the central dogma of cancer genetics, which says that a handful of essential mutations in specific genesoncogenes or tumor suppressorswreak cellular havoc and lead to uncontrolled growth. More recently, scientific discoveries are challenging this theory. In Untangling the Roots of Cancer, W. Wayt Gibbs explores these new theories, one of which is further detailed in Stem Cells: The Real Culprits in Cancer? Other notable discoveries show that inflammation plays a role in driving tumor development and asks whether or not we are evolved for cancer. The Cancer Genome Atlas points to many, many more implicated genes that we ever could have imagined. Its almost like, as Bill Hahn of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute so elegantly states, someone set off a bomb in the nucleus of a cancer cell.

Popular opinion states that screening is the best deterrent of cancer because it can detect tumors early enough so that they can be successfully treated. We look at the field of cancer screening in the second section, with selections delving into how effective mammograms for breast cancer and the PSA test for prostate cancer actually are. In his story, The Great Prostate Cancer Debate, doctor Mark Garnick lays out the rationale for not giving the test.

With our ever-increasing knowledge of the molecular basis of cancer, targeted therapies are on the rise. Selections in Section 3 explore the possibilities of homing in on stem cells, making use of viruses, and manipulating the immune system as future therapies.

The final chapter discusses ways to minimize risk. Here we explore the efficacy of a diet high in fruits and vegetables in minimizing the risk of cancer, the effectiveness of sunscreen for preventing skin cancer and how a healthy lifestyle can help impede breast cancer. Recently, weve seen the emergence of vaccines for HPV infection targeted towards adolescents, but as Katherine Harmon discusses in her story, HPV-Positive Cancers Spreading among the Middle-Aged, these infections are occurring in other populations as well. Finally, the larger question remains: Will we actually be able to truly cure cancer? Dina Fine Maron reflects on this in the concluding selection of this collection.

While there is as yet no cure for cancer, scientists continue to make strides in both basic and clinical research. With more research focusing on the intricacies of genetic causesepigeneticsas well as the increased awareness and affordability of genetic testing, its likely that even more gains will be made toward personalized therapies that treat cancer in a way more deserving of its complex nature.

--Karin Tucker

Book Editor

SECTION 1

Complexity in the Cause

Untangling the Roots of Cancer

by W. Wayt Gibbs

What causes cancer?

Tobacco smoke, most people would say. Probablytoo much alcohol, sunshine or grilled meat; infectionwith cervical papillomaviruses; asbestos. Allhave strong links to cancer, certainly. But they cannotbe root causes. Much of the population is exposedto these carcinogens, yet only a tiny minoritysuffers dangerous tumors as a consequence.

A cause, by definition, leads invariably to its effect.The immediate cause of cancer must be somecombination of insults and accidents that inducesnormal cells in a healthy human body to turn malignant,growing like weeds and sprouting in unnaturalplaces.

At this level, the cause of cancer is not entirely amystery. In fact, a decade ago many geneticists wereconfident that science was homing in on a final answer:cancer is the result of cumulative mutations thatalter specific locations in a cells DNA and thuschange the particular proteins encoded by cancer-relatedgenes at those spots. The mutations affect twokinds of cancer genes. The first are called tumor suppressors.They normally restrain cells ability to divide,and mutations permanently disable the genes.The second variety, known as oncogenes, stimulategrowthin other words, cell division. Mutationslock oncogenes into an active state. Some researchersstill take it as axiomatic that such growth-promotingchanges to a small number of cancer genes are theinitial event and root cause of every human cancer.

For the past few years, however, prominent oncologistshave increasingly challenged that theory.No one questions that cancer is ultimately a diseaseof the DNA. But as biologists trace tumors to theirroots, they have discovered many other abnormalitiesat work inside the nuclei of cells that, though notyet cancerous, are headed that way. Whole chromosomes,each containing 1,000 or more genes, areoften lost or duplicated. Pieces of chromosomes arefrequently scrambled, truncated or fused together.Chemical additions to the DNA, or to the histoneproteins around which it coils, somehow silence importantgenes, but in a reversible process quite differentfrom mutation. And scans of the genomes ofmalignant cells within tumors have found that theytypically harbor myriad rare mutations rather thana handful of common genetic alterations.